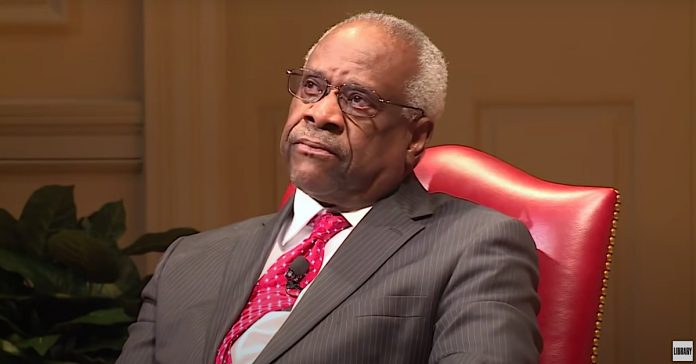

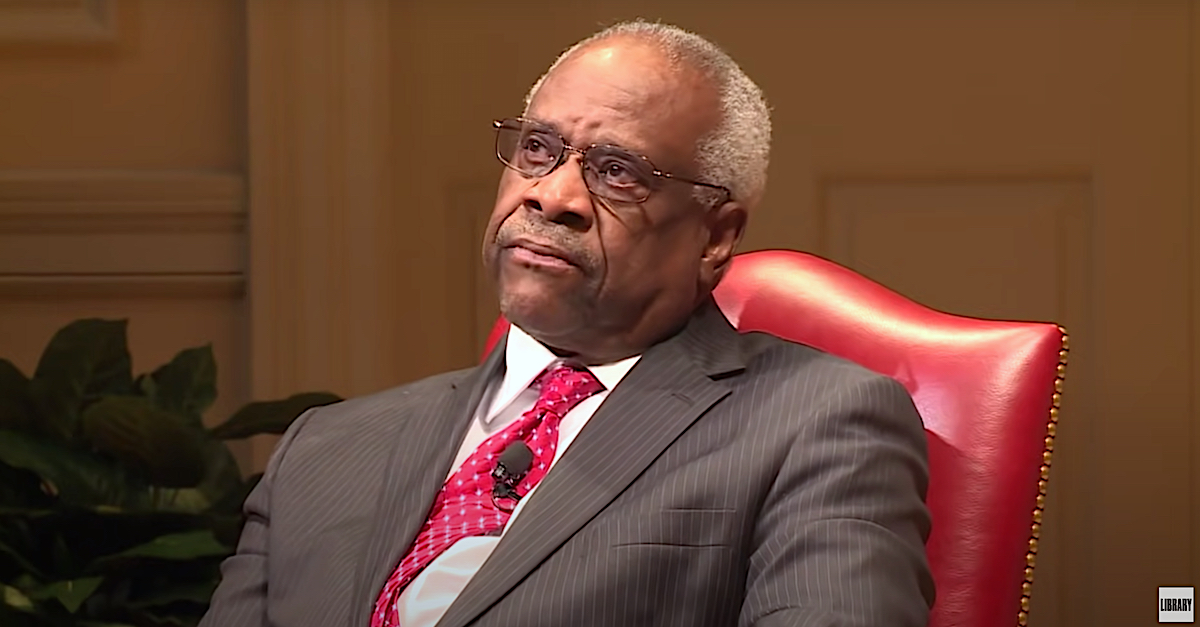

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas (via YouTube/Library of Congress).

Now that the U.S. Supreme Court has put Donald Trump’s bid for immunity from prosecution over the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol on its calendar, calls for Justice Clarence Thomas to recuse himself from the case have intensified.

But the reasons that underlie the frenzy to remove Thomas from the case are more complex than a simple assumption that the conservative justice would, as he has in past disputes, vote in favor of Trump.

Here is a closer look at some reasons Thomas might be particularly inclined to find that the former president should be immune from criminal prosecution.

1. The Ginni effect

Ginni Thomas, the justice’s conservative activist wife, is not just aligned with Trump’s rhetoric: She has close ties to Trump’s efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election.

From reports that she called Joe Biden’s victory the “greatest Heist in our History,” to her support of Sidney Powell as “the face” of efforts to overturn the election results, to her admission that she attended the “Stop the Steal” rally for Trump, Ginni Thomas has raised her voice in fervent support of Trump as winner of the 2020 election.

Though she has denied having any role in the planning of Jan. 6 events as well as the widely-circulated rumors that she paid for buses to transport others, she admitted to sending messages to then-White House chief of staff Mark Meadows about efforts to overturn the election results.

In one of the texts Ginni Thomas later regretted sending, she urged Meadows to “Release the Kraken and save us from the left taking America down.”

Ginni Thomas also raised questions about the Trump legal team’s choice to distance itself from Powell’s costly false claims about Dominion Voting Systems and Smartmatic.

Under American Bar Association rules, judges must disqualify in any proceeding in which they have “a personal bias or prejudice” about facts in dispute, or when the judge’s spouse has “more than a de minimis interest that could be substantially affected by the proceeding,” or has an economic interest in the outcome of the proceeding.

Certainly, whether Ginni Thomas’s relationship to the events of Jan. 6 and any corresponding immunity for Trump is close enough as to require her husband’s recusal would require thorough analysis. However, “more than a de minimis interest” is a very, very low standard. Given public outcry over Ginni Thomas’s close ties to the insurrection, it is indisputable that a ruling in Trump’s favor would raise serious questions about the justice’s bias or impropriety.

2. The Paxton problem

When indicted Republican Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton tried to sue on behalf of Texas to overturn the results of the 2020 election, the Supreme Court turned the case away for lack of Article III standing. The high court ruled that Texas did not have sufficient interest in the way other states conducted their own elections.

Thomas, along with Justice Samuel Alito, spoke up to say they would have allowed Paxton to proceed with his case. The conservative pair of justices framed their disagreement in terms of powerlessness, saying they did not believe the Supreme Court had the discretion to turn away Paxton’s lawsuit given because it fell within the Court’s original jurisdiction — meaning a case in which the Supreme Court would act as trier of fact.

Thomas’s position in the matter is noteworthy in that it represented a departure from the justice’s typically stringent views on standing. Whether that departure was attributable to the subject of the case or to its status as an original jurisdiction case is unknown, but suggests that Thomas may be willing to afford the Trump immunity case extra procedural protections.

3. And then there’s Nixon

In the 1982 Supreme Court ruling in Nixon v. Fitzgerald, the five-member majority said some things that might prove irresistible for Thomas and helpful for Trump. Essentially, the Court said that giving the president immunity is not all that dangerous, because there are still lots of other mechanisms to protect the nation from an out-of-control president.

Justice Lewis Powell framed presidential immunity as nothing more than a mechanism that “merely precludes a particular private remedy for alleged misconduct in order to advance compelling public ends,” as opposed to a loophole that could hand a president unfettered power.

Of course, the issue in the Nixon case was different. At the time, the Court was considering civil, not criminal immunity, and Nixon’s wrongdoing was the allegedly wrongful firing of a government official, not the incitement of a mass insurrection. Still, it is not difficult to imagine the Court’s 1982 reasoning being applied to the Trump case — particularly by conservative justices who seek to use historical precedent whenever possible to justify current decisions.

Justice Lewis Powell wrote in the Nixon case that “[a] rule of absolute immunity for the President will not leave the Nation without sufficient protection against misconduct on the part of the Chief Executive,” because presidents are subject to impeachment, “vigilant Congressional oversight,” and “constant scrutiny by the press.”

He said there are also “other incentives to avoid misconduct” such as “the desire to earn reelection, the need to maintain prestige as an element of Presidential influence, and a President’s traditional concern for his historical stature.”

If that logic were applied to the Trump case, it would create something of a circle: that Trump should be immune to prosecution for illegal efforts to reinstate himself as president, because his desire to get reelected is a safeguard against his acting illegally. Still, many of the underlying truths relevant to the Nixon decision are still true today: presidents are indeed subject to scrutiny by both Congress and the media, and both the political process and the desire for a positive legacy can be powerful catalysts for accountability.

Whether Thomas or others would use those words to justify a vote for Trump in a case with such different facts remains to be seen, but the underlying concepts mentioned by Powell are certainly applicable.

Thomas has spoken out about the need to “reexamine” immunity in other contexts in the past. He criticized the power held by tech companies because of immunity under Section 230. He has many, many times called for the Court to revamp its take on qualified immunity, which protects government officials from civil rights lawsuits.

Presidential immunity, though, is in a category by itself. And in matters that involve conflicts between branches of government, Thomas and other conservatives tend to prefer a hands-off approach.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]