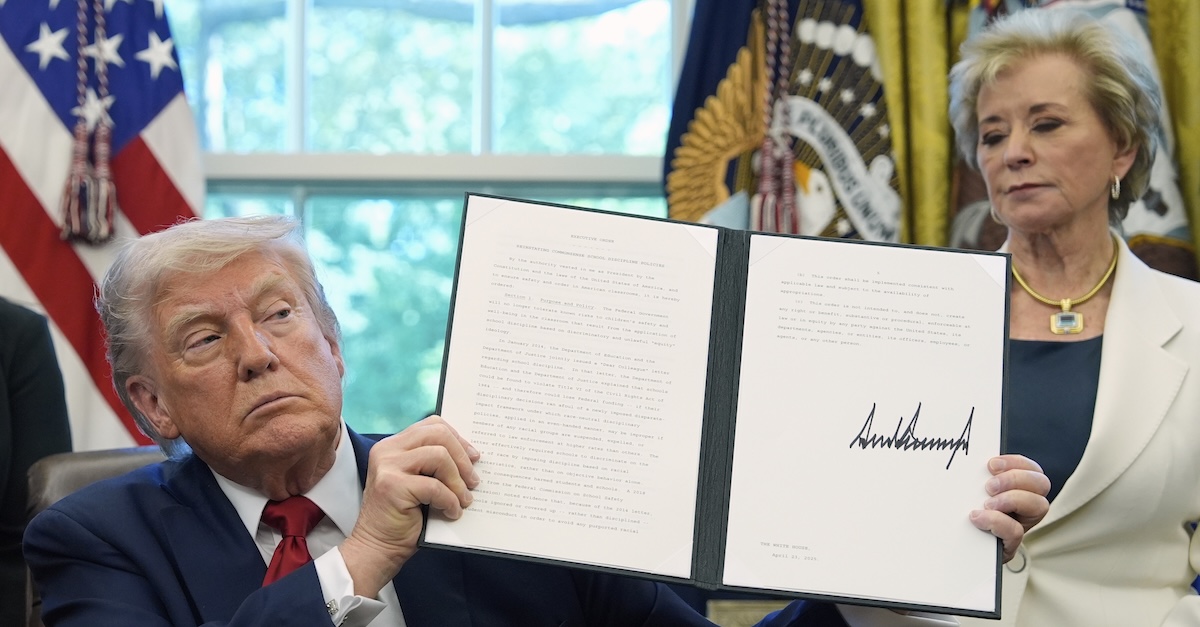

President Donald Trump holds a signed executive order relating to school discipline policies as Education Secretary Linda McMahon listens in the Oval Office of the White House, Wednesday, April 23, 2025, in Washington (AP Photo/Alex Brandon).

A federal judge in Baltimore this week gave the Trump administration a limited — but significant — victory in a case challenging the wholesale restructuring of the U.S. Department of Education.

On March 20, President Donald Trump issued an Executive Order titled “Improving Education Outcomes by Empowering Parents, States, and Communities.” The order broadly summarizes the 45th and 47th president”s long-promised plans to shutter the Jimmy Carter-era agency. Prior to that, Education Secretary Linda McMahon had issued a series of directives – including mass firings and grant rescissions – geared toward dismantling the agency.

A coalition of plaintiffs led by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sued. The lawsuit alleges that ensuing actions by the government to effectuate the order were “unconstitutional” and in violation of “Congress’s directives in creating the Department and assigning it specific duties and appropriations.” Months later, the plaintiffs moved for a preliminary injunction.

Earlier this month, the Trump administration aimed to quickly end the case by asking U.S. District Judge Julie Rubin, a Joe Biden appointee, to dismiss both the complaint and the injunction request.

Now, in a 39-page memorandum opinion, the court denied both parties’ motions without prejudice – favoring a fuller record.

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

At the heart of the dispute is the NAACP’s claim that the Trump administration is trying to shutter the Department of Education. This claim, in motions, is hotly disputed by the U.S. Department of Justice.

The judge, for her part, tends to agree with the plaintiffs – but says it does not really matter in the context of the legal claims asserted.

“The court does not doubt that Plaintiffs have made a strong showing that Defendants’ collective actions amount to an effort to close the Department,” the opinion reads. “Of course, this alone is not enough to do what they ask of the court. To grant a [preliminary injunction] motion, the court must find the movant has made a ‘clear showing’ that the ‘extraordinary and drastic’ remedy of a preliminary injunction is warranted.”

Here, the court takes the lead from the DOJ’s early August motion – and looks to case law recently developed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

In one instance, the nation’s high court stayed a preliminary injunction, effectively allowing the Department of Education to move forward with large-scale reductions in force (RIFs) affecting thousands of workers. In the second instance, a majority of justices stayed an injunction – allowing the agency to cancel some $65 million in grant funds.

Rubin finds those cases instructive.

“[T]his court is obliged to follow the direction of the Supreme Court,” the opinion goes on. “In view of the caselaw that has developed on these very topics (including the scope of relief sought), the court is unable to conclude that Plaintiffs are likely to succeed.”

Specifically, the NAACP is challenging the RIFs, the grant cuts, and a third category of actions: the cancellation of research contracts.

While the high court has yet to consider challenges to the contract issue, other courts have had the opportunity. In those cases, district courts in Maryland and the District of Columbia have denied requests for preliminary injunctions that would have maintained the contracts.

All this, the judge says, points exactly one way.

“[T]hose challenges have failed, in part, due to the ongoing legal development in this area punctuated by Supreme Court stays pending appeal in various circuits, as well as issues that flow from the very relief Plaintiffs seek here,” the opinion continues. “These various cases, including specifically (but not exclusively) the Supreme Court’s stays in New York and California, have resulted in quickly evolving and divergent caselaw that raises material questions, if not doubts, that bear on this court’s exercise of jurisdiction, the merits of Plaintiffs’ claims, and the court’s authority to order the relief sought.”

Still, the judge is careful to say she “does not read” the current legal landscape “to foreclose” against the NAACP’s claims entirely – and certainly not to “support dismissal” of the claims. Rather, Rubin says the record does not support injunctive relief at the present time.

Here, the judge takes the opportunity to telegraph some minor criticisms of how, exactly, the high court’s majority has ruled on the cases – noting that the stays came “without accompanying reasoned analysis.” This is an implicit reference to what legal scholars have long referred to as the Supreme Court’s “shadow docket.”

In shadow docket cases, the court’s majority often pens highly influential rulings – in terms of real-world impact – without full analysis that would allow lower courts to discern what, if any, precedent is being created. Critics say these rulings tend to fall along starkly partisan lines in the conservative Roberts Court.

But, Rubin says, they are still Supreme Court rulings after all.

“These stays of orders implementing much of the exact relief sought here, on fundamentally similar claims raise serious concerns about this court’s authority to order the relief Plaintiffs seek,” the opinion reads. “The court is acutely aware that a ‘stay order is not a ruling on the merits,’ however, the Supreme Court’s California and New York stays necessarily called upon the Court to conclude that the Government is likely to prevail.”

The judge also says the plaintiffs veer near territory the high court expressly forbid in the landmark case barring universal injunctions.

“The relief requested here raises a serious risk of doing precisely what the Court has cautioned the court to avoid,” Rubin’s analysis concludes. “Ultimately, this court may not overreach its authority to order the Executive to act within the confines of its own.”

Citing “material overlap” between both parties’ motions, the court also “administratively” denied the DOJ’s motion to dismiss. Rubin says this move is “for efficiency and clarity of the record, and to enable the parties a more fulsome opportunity to hone their arguments against the backdrop of the court’s analysis.”