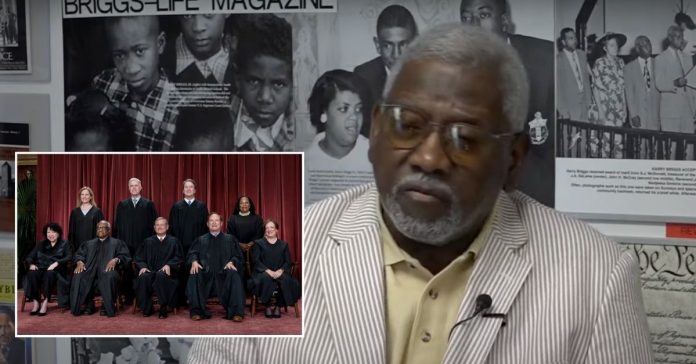

Main: Nathaniel Briggs discusses his petition to the Supreme Court to change the name of the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka to Briggs v. Elliott (Screengrab via YouTube/WLTX). Inset: the justices of the United States Supreme Court are shown. (Alex Wong/Getty images).

The United States Supreme Court declined to even consider correcting a clerical error that descendants of civil rights activists say resulted in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka being known by the wrong case name for nearly seven decades. According to the family involved, an “inadvertent clerical misstep” has deprived them of “their rightful place in history in spite of the great physical, emotional, and financial risks” taken by their loved ones.

During the early 1950s, five cases challenging the constitutionality of state-sponsored racial segregation in schools reached the Supreme Court: Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Briggs v. Elliott, Davis v. Board of Education of Prince Edward County (VA.), Bolling v. Sharpe, and Gebhart v. Ethel. The cases arose from different school districts and had different underlying facts, but focused the same central legal issue.

In 1952, the Supreme Court consolidated all five cases under the name Brown v. Board of Education. Renowned civil rights lawyer Thurgood Marshall, who went on to become the first African American Supreme Court justice, argued the cases on behalf of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. The court’s 1954 ruling — that “separate but equal” facilities for Black people and white people are inherently unequal and therefore violative of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment — became one of the most well-known precedents in legal history.

Nathaniel Briggs, the son of Harry and Eliza Briggs of the Briggs v. Elliott case, said in a November 2023 filing that the case should never have been known as “Brown,” and that notoriety connected with the momentous civil rights victory should have belonged to their family. Without a correction, the Briggs family’s role in Southern school desegregation would continue as little more than a footnote to history, they argued.

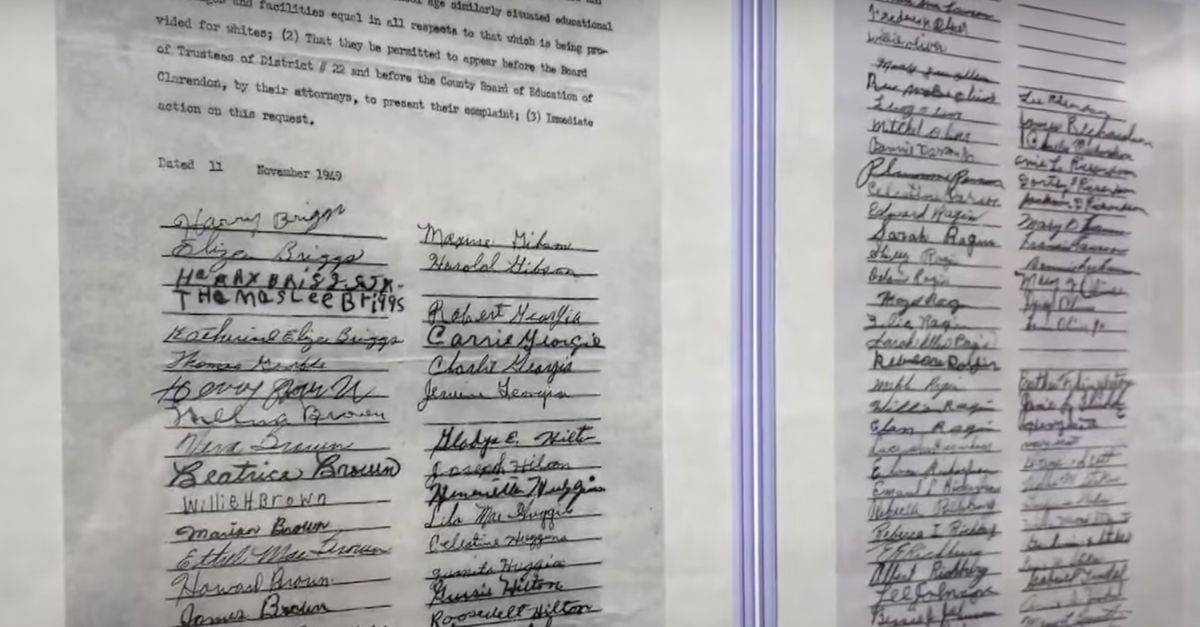

The signature lines from the case that came to be known as Briggs v. Elliott is shown with Henry and Eliza Briggs as the top two plaintiffs (screengrab via YouTube/WLTX).

Attorney Thomas Mullikin, who represented Nathaniel Briggs and his five children in their 2023 filing, told press at the time that Briggs v. Elliott had actually been the first case filed and deserved the name recognition instead of the Brown case.

“Being first in life sometimes does matter,” Mullikin quoted from his clients’ petition.

“These petitioners stood courageously for a matter of great importance only to find themselves in harm’s way and their place in history discarded,” argued the petitioners in their 2023 petition to the justices.

The relative timing of the various cases is a somewhat complicated matter. The Briggs plaintiffs filed a lawsuit in 1951 in the Eastern District of South Carolina that challenged segregated school bus transportation. A three-judge panel granted an injunction to equalize educational facilities in the county and ordered it to desegregate within six months. However, it denied an injunction abolishing segregation altogether on the grounds that there was no legal precedent for such a decision. The Briggs petitioners appealed the denial and while that appeal was pending, a district court in Kansas decided Brown v. Board of Education.

Over the next three years, the various desegregation cases were appealed, re-heard, and re-appealed several times. Briggs was the first of the cases appealed to the Supreme Court and according to the current Briggs petitioners, it was the panel’s decision in the Briggs case that became the ultimate basis for the Court’s decision in what became known as Brown v. Board of Education.

The current petitioners said that at the time, the court clerk incorrectly docketed Brown before Briggs — a simple error that had the dramatic result of relegating the courageous Briggs plaintiffs to being simply “a companion case” to Brown that thereafter “faded into relative anonymity.” They urged the Supreme Court to correct the record, recognize the Briggs family for their great sacrifice, and put an end to the “misappropriat[ion] of their rightful place in history.”

In their petition to the Supreme Court, the current Briggs petitioners gave context for what it meant for their family members to become civil rights plaintiffs in the segregated South:

In the sweltering heat of segregation in the South, families assembled to sign a petition challenging the egregiously unfair education system. For some, signing was tantamount to a death sentence. This valiant act would strike a match that would lead the civil rights movement across the country and cost these heroic families their physical, emotional, and economic security.

Those petitioners “faced unimaginable physical and financial terror,” and risked “horrible deaths” and “unspeakable emotional and physical threats,” the petition continued. Still, the courageous petitioners “stood for righteous relief in the presence of bitter hatred” that cost them dearly.

“To subordinate these courageous Americans is to deny the very significance of our jurisprudence as the fair and blind system that provides a path for meaningful redress of inequities rather than through less legitimate means,” read the brief. “Being first sometimes matters.”

The Briggs family also argued that using the caption from the Kansas case was especially unfair given the context of the two locales.

“Unlike Briggs, which arose in the deep south, Brown was a case out of Topeka, Kansas,” they explained. Black schools in segregated South Carolina at the time were not only “dilapidated, overcrowded, and underfunded” to a greater degree than their counterparts in Kansas, but the Topeka school district also began integrating its schools as early as 1941.

The justices were apparently unconvinced. The Supreme Court denied the petition for writ of mandamus Monday without comment.

In an email to Law&Crime Tuesday, Mullikin said he was disappointed with the Court’s decision not to hear his clients’ case and noted that, “the Briggs petitioners stood for righteous relief in the presence of bitter hatred that cost many of them their lives and small economic fortunes.”

Mullikin also said:

The South Carolina case of Briggs v. Elliott was the first case filed in federal district court; Briggs was the first case appealed to the United States Supreme Court; Briggs was argued by the future United States Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall; and the dissenting opinion written by U.S. District Court Justice Waties Waring became the basis of the ultimate decision of the court. Our petition was simply to pay gratitude to these brave and

determined South Carolinians who led our nation to a stronger, better and more equitable education

Editor’s Note: This piece was updated to include comment from counsel.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]