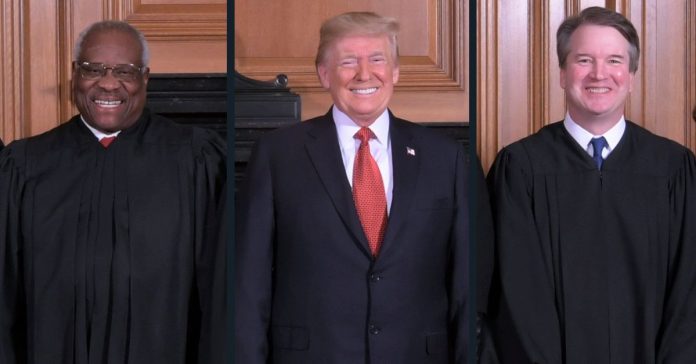

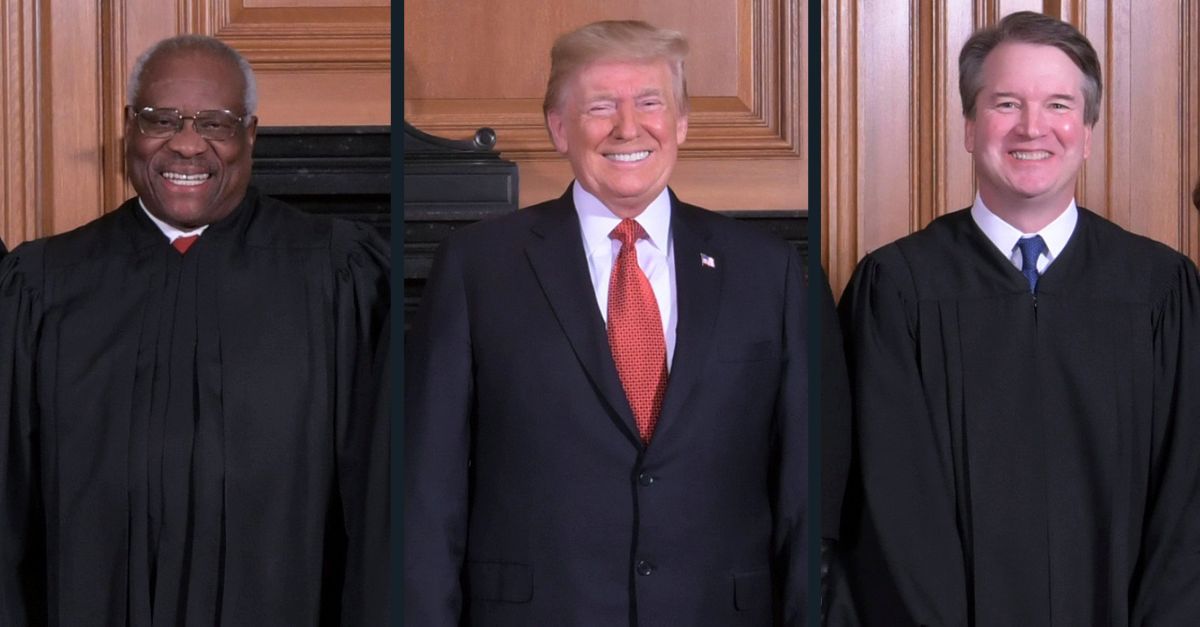

In this image provided by the Supreme Court, President Donald Trump (center) poses for a photo with Associate Justice Clarence Thomas (left) and Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh (right), in the Justices’ Conference Room before a investiture ceremony Thursday, Nov. 8, 2018, at the Supreme Court in Washington. (Fred Schilling/Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States via AP).

The justices heard much-anticipated oral arguments Thursday as they considered whether the state of Colorado has the authority to declare Donald Trump disqualified from seeking a second term as president.

The Court must review the Colorado ruling that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, known as the “disqualification clause,” is “self-enforcing” and can be used by a state to keep an insurrectionist off the presidential ballot — or if an act of Congress is required.

The disqualification clause served to protect the post-Civil War federal government from the risk of former Confederate civil and military officeholders holding government office and throwing the country into chaos. The need was relatively short-lived, because in 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Amnesty Act, which removed the prohibition against former Confederates holding office and pardoned secessionists for their participation in the Civil War.

The Supreme Court’s conservative justices are known for their prioritizing of historical bases for rulings. In the Trump case, the relevant history is both scant and conflicting. That did not, however, stop some justices from looking backward into history as they questioned the plaintiffs’ attorney, Jason Murray.

Justice Clarence Thomas began by asking Murray to provide “contemporaneous examples” from the time of the adoption of the 14th Amendment that would support his argument that Colorado is authorized to disqualify a presidential candidate.

Murray was ready for the question and offered a single example: John H. Christy. Christy won a congressional election in Georgia in 1868, but was stopped from taking office when Georgia’s governor learned that Christy had been a Confederate and declined to certify the results of the election, finding Christy disqualified.

Murray noted in his response to Thomas that the scarcity of similar historical examples was unsurprising due to the way elections were carried out during the 1800s. At the time, Mitchell said, names of presidential candidates were not printed on advance ballots in the way they are now. Rather, candidates names would be written in by voters on Election Day. Therefore, there would have been neither a need nor a mechanism for declaring a candidate disqualified before that candidate were actually elected.

Thomas, however, barreled on, undeterred by Mitchell’s explanation and repeating the same call for historical examples.

“But it would seem that, particularly after Reconstruction and after the Compromise of 1877, and during the period Redeemers, that you would have that kind of conflict,” the justice said. “There were a plethora of confederates still around, there were any number of people who would still run for state office or national offices so that would suggest that there would at least be a few examples of national candidates being disqualified — if your reading is correct.”

Mitchell agreed that there were certainly former Confederates who were disqualified by Congress refusing to seat them.

Thomas pushed, saying congressional disqualification is not what is at issue in the Trump case.

“Did states disqualify them?” asked the justice.

Mitchell answered again that the lack of examples were “unsurprising,” because elections were handled without the step of putting candidates on a ballot as we do know.

Thomas did not let it go.

“If you are right, what are the examples?” he demanded.

“There are people who felt very strongly about retaliating against the South, the radical Republicans,” lectured Thomas, “but they didn’t think about letting the South disqualify national candidates.”

Murray answered that historians filed briefs that support his argument in the case, and told Thomas for a third time that elections were simply different during the 1800s. Although states did have the power to run their own elections, they did not begin using that power to police the ballot process until the 1890s, he said — and by that time, the former Confederates had all been pardoned.

Chief Justice John Roberts joined the fray to paraphrase Thomas’ unusual take on the 14th Amendment. Roberts summed up, saying that since “the whole point of the 14th Amendment is to restrict states’ power,” it would be “the last place you would look” as a basis for state authority to disqualify a national candidate. In other words, if the 14th Amendment were meant to neuter the Southern states, it would not have simultaneously handed those states control over the presidency.

Murray later pointed out in a colloquy with Justice Brett Kavanaugh that there is no shortage of historical examples of states having authority to disqualify a presidential candidate for reasons unrelated to insurrection.

“I don’t take it that there’s a great debate about whether or not states are allowed to excuse underage or foreign-born candidates, or if President Bush or Obama wanted to run for a third term, they could be excluded,” Murray argued.

Kavanaugh later attempted make the point that the lack of similar historical examples supports Trump’s position in the case. Kavanaugh said that in his mind, the reason why state attempts to disqualify candidates “have been dormant” is because there a “settled understanding for 155 years” that the authority belonged only to Congress.

Murray was unwilling to share Kavanaugh’s take on history.

“No, Justice Kavanaugh,” he snapped. “The reason why it’s been dormant is because by 1876, essentially all the confederates had received amnesty.”

“And we haven’t seen anything like an insurrection since then,” Murray added.

Justice Samuel Alito took the chance to make his own point: history does not always repeat itself.

“I don’t know how much we can infer from the fact that we haven’t seen anything like this before, and therefore conclude that we’re not going to see something in the future.”

Alito noted that while 100 years passed between the impeachments of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, there have been three impeachments in recent history.

You can watch the full oral arguments here.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]