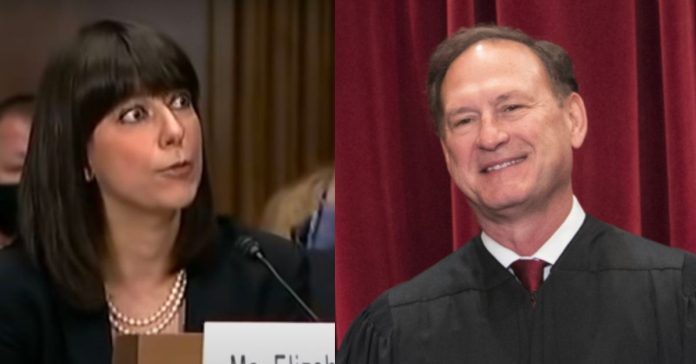

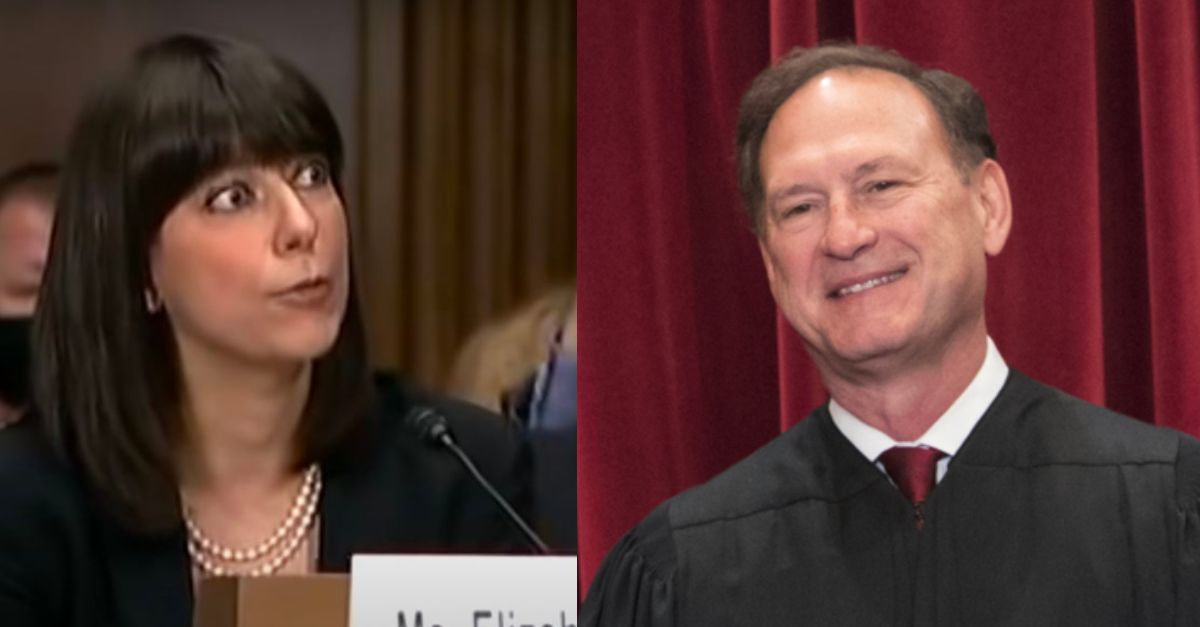

Left: Solicitor General of the United States Elizabeth Prelogar (screengrab via YouTube); Right: Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Samuel Alito (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

All nine justices of the Supreme Court of the United States — including Samuel Alito, who refused to recuse himself despite calls to do so — participated in Tuesday’s oral arguments in a case asking whether a Donald Trump-era “wealth tax” violates the Constitution. Alito had been asked to recuse himself because he had previously been interviewed by an attorney involved in the case, but the justice said there was no reason for him to avoid participating.

The case is Moore v. U.S., and it could have major implications on the federal government’s power to levy taxes under the Constitution.

The tax issue

The Sixteenth Amendment, ratified in 1913, allowed the federal government to collect income taxes (as opposed to property taxes) without the necessity that the taxes be apportioned among the states. Prior to the amendment, nationwide income tax laws were often challenged, repealed, then readopted. After the amendment, the federal government’s tax power became robust and broad. At issue before the Court is whether that power is so broad as to permit Congress to impose an unapportioned tax on “unrealized” sums — those investment profits that exist only on paper and before they are sold for cash.

The dispute involves Charles and Kathleen Moore and their 2005 investment in KisanKraft, an Indian corporation that supplies small farmers in India with modern tools. The couple received about 13% of the shares in KisanKraft in exchange for their $40,000 investment. Over the next many years, the Moores received no dividends or other distributions, though the company flourished. KisanKraft reinvested its profits in the business so that it could expand.

Neither KisanKraft’s earnings nor any increase in value of their shares was a taxable event for the Moores until 2017, because any income that may have occurred did so outside the U.S. However, a year after Trump was elected president, Congress enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act with its “mandatory repatriation tax” or “MRT.” The MRT, which intended to raise hundreds of billions over the next decades, imposed a one-time tax on a controlled foreign corporation’s earnings after 1986 even for those shareholders who did not receive distributions. The Moores owed $15,000 in taxes under the plan.

The Moores paid the MRT, then sued for a refund on the grounds that the mandatory repatriation tax violates the Constitution’s apportionment clause. Their argument — which was rejected by the district court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit — was that the Moores’ shares in KisanKraft were their personal property and not income, and that the Constitution requires each state to tax personal property in a manner proportional to its population. In other words, they said that the 2017 tax law was improper, because it taxed the wrong thing in the wrong way.

The Ninth Circuit disagreed with the Moores and held that “realization of income is not a constitutional requirement” for taxes and there was “no constitutional prohibition against Congress attributing a corporation’s income pro rata to its shareholders’ and then taxing them on it, as happened here.”

The Moores, supported by numerous amici, appealed to the Supreme Court hoping that the Court’s wariness against all things administrative agency might mean a ruling that would prevent Congress from ever enacting other “wealth taxes” on the value of assets or other investments.

The Alito issue

Alito refused to recuse himself in the case, even after being formally requested to do so by a leading member of Congress. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal in July, Alito spoke about his “controversial view” that the Constitution does not specifically authorize Congress to regulate the Supreme Court. One of the bylines in the article belonged to David Rivkin, an attorney who represents the Moores in the case before the Supreme Court.

Last August, Sen. Dick Durbin, an Illinois Democrat serving as the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, sent a letter to Chief Justice John Roberts regarding Alito’s Wall Street Journal interview. Durbin said that while the Moore case was pending, Alito sat for two interviews with Rivkin and that the personal contact “could cast doubt on Justice Alito’s ability to fairly discharge his duties in a case in which Mr. Rivkin represents one of the parties.”

Alito denied there was any valid reason for recusal and noted that those connected with media entities frequently have cases before the justices. Alito said that Rivkin was a “much-published opinion-journalist and a practicing attorney,” and that there was nothing “out of the ordinary” about the interviews during which Rivkin acted as a journalist and not an advocate.

Trump taxes, championed by Biden’s DOJ

Attorney Andrew Grossman represented the Moores in Tuesdays lengthy oral arguments.

An overtly skeptical Justice Sonia Sotomayor suggested that Grossman’s theory in the case could undermine the entire idea of corporate structure. Sotomayor said that history provides many examples of Congress taxing unrealized income. The justice warned that what Grossman was suggesting — “to announce what ‘realization’ is out of context” — is something the Court has specifically avoided doing for over 100 years, because it is “dangerous.” Rather, Sotomayor said, considering the issue as one of pass-through income from KisanKraft itself to the Moores, would not require such a bold rule.

When she took the podium for the Department of Justice, Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, appointed by President Joe Biden 2021, gave nothing less than a full-throated defense of Trump’s 2017 MRT. Prelogar fielded the justices’ questions with ease as she argued that the MRT is consistent with the “historical tradition” of other taxes and that ruling it to be constitutionally deficient would cripple federal taxation efforts and create loopholes for those attempting to hide income in offshore accounts.

Alito began a series of questions to Prelogar by asking about an argument that Alito noted “has resonated a lot in [media] coverage of this case.”

“The adoption of Petitioners’ argument would have far-reaching consequences in this case, isn’t that correct?” Alito began. “Do you think it is fair then, to explore what the consequences of what your argument would be?” he challenged.

Prelogar said that while she was happy to respond to Alito’s question, the Court could actually rule “quite narrowly” in the case. She continued, reminding Alito that the Court need not announce any bright-line rule about income generally, and could confine its ruling to a particular kind of undistributed earnings. Justice Brett Kavanaugh interrupted Alito’s line of questioning to underscore the point that the case could be decided even without considering the Moore’s earnings “unrealized” — and rather, consider those funds “earned” by the corporation itself and then simply “attributed” to the Moores as shareholders.

Alito was clearly unconvinced, and tag-teaming with Justice Neil Gorsuch, the two raised and refined several hypotheticals.

“Let’s say that somebody graduates from school and starts up a little business in his garage and 20 years later, 30 years later, that person is a billionaire,” Alito began and asked. “Under your argument, can Congress tax all that on the ground that it is income?”

Prelogar was ready for the question and responded, “Sounds to me that the hypo is actually functioning as a property tax.”

In response, Alito changed the facts a bit and asked about the appreciation of stock value over two or three decades.

Prelogar called that a “harder question,” but said that it is one without a history and tradition that supports such a tax.

Gorsuch, the Court’s fiercest opponent of federal administrative agencies such as the IRS, picked up on Alito’s line of questioning and asked about “millions of Americans” with small investment or retirement accounts. Prelogar said such a tax would not necessarily be invalid.

Gorsuch parried and characterized a ruling in the DOJ’s favor one that could require overturning 100 years of precedent. At the next opportunity, Justice Elena Kagan seized the chance to press the point.

Justice Gorsuch said you were asking us to overrule 100 years of our precedent,” Kagan commented. “Sounds bad. Are you?”

Prelogar responded that she was not asking the Court to overrule anything, but rather, to follow its own precedent.

Alito then circled back to Gorsuch’s earlier question and asked again about the “millions of Americans” with mutual funds.

“Without selling the shares in those mutual funds, can that be taxed under the Sixteenth Amendment?” asked Alito.

“I think if Congress actually enacted a tax like that — and it never has — that we would likely defend it as an income tax,” came Prelogar’s response.

“But you don’t have to agree that that tax would be valid to uphold the MRT,” she added, dodging Alito’s volley.

The blunt and often comedic Kagan could not resist throwing a few barbs Alito’s way via contextualizing Prelogar’s comments.

Kagan said Alito’s hypothetical presented “a number of taxes which we’ll probably never see in our lifetimes,” and reminded Prelogar that she answered that if she did see them, she would probably defend them.

Kagan then asked the Biden appointee, “When you say that, that’s your job right?”

“Yes, we generally defend the constitutionality of statutes,” answered the solicitor general, chuckling.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]