A young person does a video call in the video room next to the St. Clair jail lobby. Photo provided in civil complaint against St. Clair County officials and Securus Technologies. Inset: Sheriff Mat King, St. Clair County, Michigan (YouTube/CTV Community Television screengrab, 2021).

Children and families in Michigan say they are being stripped of their right to see their incarcerated loved ones in person for years just so county officials and prison telecom companies and their partners can reap lucrative profits in an illegal kickback scheme while the families suffer long term consequences.

The allegations are found in a pair of class action lawsuits filed last month in Michigan. The class actions are separate, and the group of plaintiffs in both are diverse and are made up of parents and family members of inmates incarcerated in St. Clair and Genesee County, Michigan.

Represented by their parents or guardians, some plaintiffs are as young as just 2 years old. Many are preteens on the verge of life’s big changes from childhood to adolescence and have told the court they are looking for connection and guidance from their parents despite the circumstances.

At least one plaintiff is the mother of an incarcerated woman who alleges that an underlying scheme to cut off in-person visitation in favor of video-call visits only has relegated her relationship with her daughter to a series of dropped calls, slowly eating away at their relationship and contributing to the destruction of their mutual well-being.

One of the class action lawsuits is filed against Sheriff Mat King of St. Clair County, Michigan, and names the prison telecom company Securus Technologies and its parent owner Platinum Equity. It is specific to inmates housed in St. Clair County Jail and alleges that the kickback scheme that forced families into an “impossible position” originated in 2017.

The other class action stems from an even older ban on in-person visitation in Genesee County, Michigan. This started in 2014, according to the lawsuit filed in the Seventh Circuit Court for the County of Genesee. This complaint names Sheriff Christopher Swanson in Genesee County as well as Global Tel*Link Corporation which does business as ViaPath Technologies.

The allegations in each claim largely mirror one another.

In St. Clair, for example, when the in-person family visitation ban went into effect in 2017, it forced “families desperate to maintain some form of contact with their loved one, however inferior” to choose between paying $12.99 for 20 minutes of “painfully inadequate video” or paying for basic necessities like food, rent, gas or hygiene products.

“Even these low-quality video calls are completely inaccessible to many because of their price tag, because of the required technology, or because the video call format is meaningless for infants, neuro-divergent children, and people with various disabilities. Many people will not see their loved one’s face — even as a frozen or pixilated image on a screen — for months or years until they are released or transferred,” the 96-page St. Clair complaint states.

Securus is alleged to pay St. Clair County 50% of that $12.99 and 78% of the 21 cents per minute cost of each and every phone call among inmates, the class action states. Text messages cost a 50 cent “Stamp” plus a $3.75 transaction fee to purchase them.

Securus is charging families “exorbitant rates” to talk to inmates while it garners a guaranteed contract that St. Clair County would pay the company at least $190,000 annually, the plaintiffs say.

At bottom, the contracts incentivize jails to go to an all-digital visitation format and it was this bargain that allowed Securus, for example, to install its own digital kiosks where in-person visits once took place.

The Michigan Constitution enshrines the “fundamental” rights of intimate association and family integrity, lawyers for the St. Clair plaintiffs write. That means that the integrity of parent-child relationships, even for incarcerated parents since their children and family members are entitled to keep their relationships alive through physical contact, too.

Under the visitation ban in St. Clair, “children and parents are unable to look directly into each other’s eyes, hold each other’s hands, give each other a hug or otherwise maintain the in-person connection that are essential to intimate family relationships.”

At best, they say videos are “grainy and jerky” and malfunction or show only a “green screen where the caller should be.” The audio is frequently no better: it is muffled and garbled and family members must strain to hear over the din over background noise from the inmate’s housing pod, the plaintiffs say. Sometimes, the plaintiffs say, there is no audio at all. And when the video call option completely vanishes — whether it is because the inmate wasn’t released from their cell on time or because the call didn’t connect or because the call kiosk malfunctioned, or the quality was too poor — the plaintiffs say their money isn’t refunded.

The St. Clair lawsuit was accompanied by affidavits from some of the children of the incarcerated. They, their parents and expert testimony from doctors and psychologists consulted for the case urge that “completely separating children from their parents — keeping them from seeing and touching one another” is similar to “torture.”

“Such separation causes children and parents serious adverse health effects that follow them into adolescence and adulthood. As a result of Defendants’ Family Visitation Ban, the children and parents bringing this case have experienced grievous harm that will change them for the rest of their lives,” they allege.

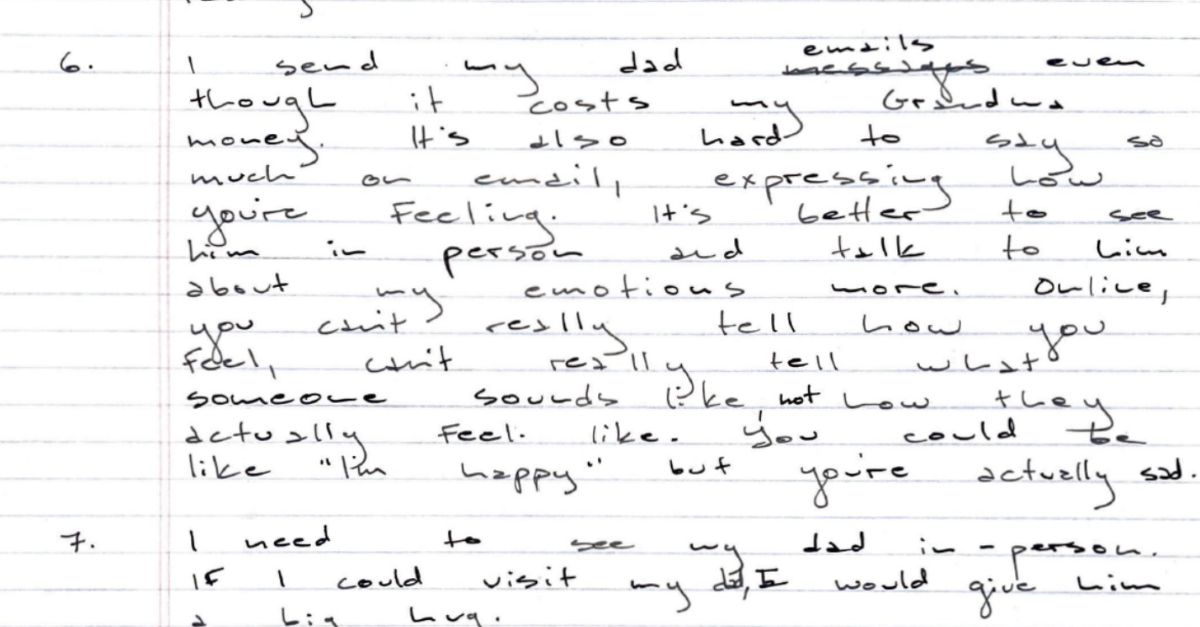

In one affidavit from plaintiff M.M., a 12-year-old whose father is incarcerated in St. Clair, they expressed how difficult it is to say how “low” you are feeling on an email:

It’s better to see him in person and talk to him about my emotions more. Online, you can’t really tell how you feel, can’t really tell what someone sounds like or what they actually feel. You could be like, ‘I’m happy’ but you’re actually sad.

I need to see my dad in person. If I could visit my dad, I would give him a big hug.

I know this is happening to a lot of other kids and parents. I’ve talked to lawyers about what it means to be involved in a class action. I want to be a part of this case so I can help other kids like me be able to see their parents and help parents like my dad be able to see their kids.

A handwritten affidavit from an inmate’s 12-year-old child (via complaint against St. Clair County officials and Securus Technologies).

In the Genesee complaint, more than a half dozen children as well as adult family members say the county had a similar setup with Securus until July 2018 when it switched over to Global Tel*Link. That deal proposed a fixed commission on the phone call system of $15,000 a month, or $180,000 annually — regardless of monthly call usage.

The plaintiffs say this was a 25% increase over the kickback revenue it was getting from Securus before Genesee County switched to Global Tel*Link, or GTL.

“In addition, GTL offered a $60,000 yearly cash bonus it called a ‘technology grant’ and 20-percent of video call revenue, estimated at $16,644 annually, and subject to considerable increases if the county defendants could accomplish a large video-call volume,” the complaint states.

All told, the county stood to make a minimum of $240,000 for each year of the contract it secured.

In 2018, GTL and Genesee County set the price for remote video calls at $10 for 25 minutes and “stipulated that Genesee County would receive a 20% commission paid out monthly.”

These “monopoly contracts” are creating huge burdens on people who are already low-income and have no choice but to pay the fees the companies and county set, the lawsuit says. A June 2021 report in Business Insider, the plaintiffs in the Genesee lawsuit note, found that the exceedingly high cost of prison phone calls raked in $1.4 billion while women and people of color were driven into debt.

Both lawsuits seek an immediate end to the bans on in-person visits.

An spokesperson for Securus’ parent company, Aventiv Technologies, told Law&Crime in an email Monday that the case against them in “misguided and without merit.”

“We look forward to defending ourselves, and we will not let this suit detract from our successful efforts to create meaningful and positive outcomes for the consumers we serve,” the spokesperson said.

Swanson and King did not respond to request for comment.

An attorney representing the plaintiffs in St. Clair County, Cody Cutting of Civil Rights Corps, said in an email Monday that the next steps will be for the sheriff and county in each case to respond to their request for the preliminary injunction and then a hearing will be held to air out the evidence in each case. The hearing in Genesee is slated for April 15; plaintiffs in St. Clair meet on April 29.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]