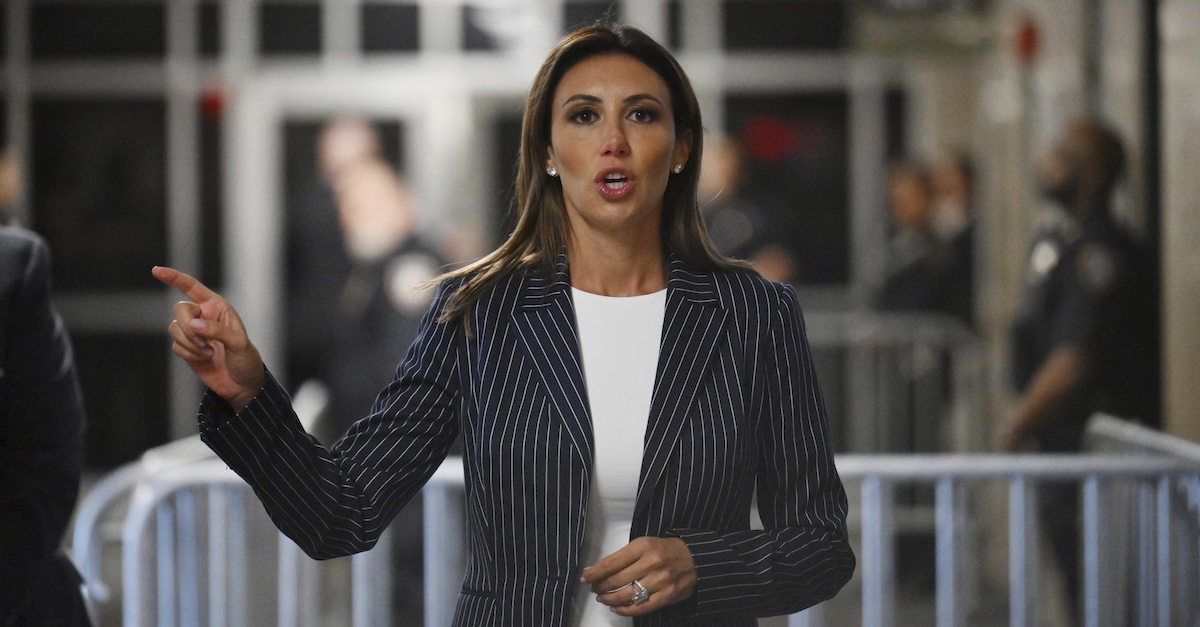

Alina Habba, an attorney for former President Donald Trump, speaks outside at Manhattan criminal court during Trump”s trial in New York, on Monday, April 22, 2024. Opening statements in Trump’s historic hush money trial began Monday. Trump is accused of falsifying internal business records as part of an alleged scheme to bury stories he thought might hurt his presidential campaign in 2016 (Angela Weiss/Pool Photo via AP).

Though he refused to dismiss a drug-trafficking indictment, a federal judge said he wants to hear more about whether U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi unlawfully reappointed acting U.S. Attorney Alina Habba to her role, opening the door to scrutiny of the Trump administration’s method of apparently sidestepping a court and the U.S. Senate’s blocking of certain nominations.

Chief U.S. District Judge for the Middle District of Pennsylvania Matthew Brann, sitting by designation in the criminal cases of Julien Giraud Jr. and Julien Giraud III after the New Jersey district court declined to appoint Habba itself upon the expiration of her 120-day acting limit, decided Friday that the Girauds were “not entitled to dismissal.” At the same time, the defendants made a persuasive enough case for “additional argument regarding the legality of Ms. Habba’s appointment” and the authority of the assistant U.S. attorneys under her command or supervision.

“I begin with dismissal of the indictment, which I conclude is not available, and then turn to injunctions against Ms. Habba and anyone acting under her authority, which I conclude would be appropriate if the Girauds prevail on the merits,” the judge wrote.

Regarding dismissal, Brann determined that the Girauds could not credibly argue their indictment, obtained through the Senate-confirmed then-U.S. Attorney Philip Sellinger, is “somehow retroactively taint[ed]” by Habba’s appointment, whether or not that was lawful.

But the Girauds can still make their best pitch for blocking Habba, and her assistants, from prosecuting them going forward.

“The Girauds argue in the alternative that Ms. Habba should be enjoined from prosecuting their case, and that any AUSAs acting under her supervision be similarly barred. As discussed in the previous section, the Court generally agrees that this remedy would be the appropriate response to the constitutional and statutory violations the Girauds claim,” the judge wrote. “This relief raises two questions: (1) can the Court bar Ms. Habba from participating in the Girauds’ prosecution, and (2) does a bar on Ms. Habba’s participation extend to AUSAs?”

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox

“As to the first question, I conclude that the answer is yes,” Brann added.

The answer to the second question, about Habba’s AUSAs, was more nuanced. Brann indicated he would not go so far as to block the whole office from prosecuting, but that he could when these prosecutors “do so under Ms. Habba’s authority” — again, if her reappointment was illegal.

“To be clear, the Court is not suggesting that it might impose the ‘officewide disqualification’ the Government fears,” the judge said. “Instead, the Court agrees that a valid remedy for the violations the Girauds’ assert, if I find that they occurred, may be to bar AUSAs from engaging in prosecutions when they do so under Ms. Habba’s authority.”

The line prosecutors or a higher-up DOJ official could still legally come to court under AG Bondi’s authority, with Habba in effect recusing herself and not putting her name and title on any filings, Brann said.

“The Court sees no reason why AUSAs acting directly under the delegated authority of Ms. Bondi, or possibly another Department of Justice official with sufficient authority to extend Ms. Bondi’s powers to AUSAs in New Jersey, would need to be disqualified,” he explained. “Moreover, so long as it is clear that they are acting under Ms. Bondi’s—and not Ms. Habba’s—authority (essentially a temporary recusal until this matter is resolved), there would appear to be no issue with all of District of New Jersey’s AUSAs moving prosecutions forward now.”

Along the way, even as the judge blasted as “misplaced” the Girauds’ challenge of Habba’s authority for relying on U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon’s Appointments Clause-based dismissal of special counsel Jack Smith’s Mar-a-Lago prosecution of Trump, Brann also had some stern words for the DOJ.

The judge noted that he had ordered both the defendants and the DOJ to submit briefs under the assumption that Habba was unlawfully appointed, yet the DOJ included an argument that said Habba was lawfully appointed one way or another.

Recall that in order to keep Habba as acting U.S. attorney Trump pulled her nomination. Habba resigned before her acting 120-day stint technically expired and before her first assistant Desiree Leigh Grace’s appointment by court as U.S. attorney became effective.

Bondi promptly fired Grace and then reinstalled Habba, citing the Federal Vacancies Reform Act when naming Habba first assistant in the U.S. attorney’s office. At the same time, just in case anyone questioned that legal authority, Habba was named a “Special Attorney to the United States Attorney General” under a federal statute governing the commission of special attorneys, giving her the power to act as a U.S. attorney through another means.

Brann said the DOJ violated his order by citing the latter authority in support of Habba, putting the proverbial “cart before the horse.”

“The Government’s argument to the contrary puts the cart before the horse. It argues that no remedy is available to the Girauds by simply rejecting the premise—which I ordered them to assume—that Ms. Habba has been illegally appointed, instead contending that she is legally exercising the powers of the United States Attorney through a delegation of the Attorney General’s power to conduct and supervise ‘all litigation to which the United States . . . is a party’ as a ‘Special Attorney’ or in her role as the First Assistant United States Attorney,” he wrote.

“But that is explicitly a merits argument: the Girauds are only entitled to no remedy if the Court finds that Ms. Habba’s appointment as a Special Attorney is valid or that Ms. Bondi can delegate a First Assistant a level of authority commensurate with the United States Attorney’s,” Brann continued. “Because it violates my Order, I do not consider the argument at this stage.”

The judge added that the DOJ’s maneuvering has “extreme implications that it openly embraces,” making a full briefing and oral argument on the “completely novel question” appropriate.

“[B]y using the Special Attorney designation and delegation, Ms. Habba may exercise all of the powers of the United States Attorney without being subject to any of the statutory limitations on that office,” Brann wrote, summarizing the DOJ’s argument. “Whether the Attorney General may statutorily or constitutionally delegate all of the powers of a specific office created by separate statute and constrained by its own statutory limitations in order to evade those limitations is a completely novel question, and one that inherently implicates the Appointments Clause and thus the merits of the Girauds’ motion. I defer resolving it until it has been fully briefed.”