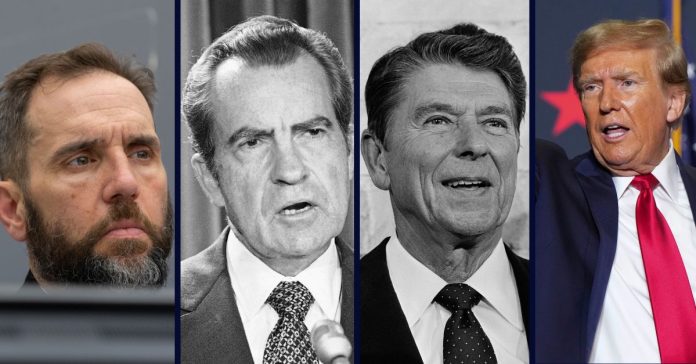

Left to right: Prosecutor Jack Smith of the U.S. waits for the start of the court session of Kadri Veseli’s initial appearance at the Kosovo Specialist Chambers court in The Hague, Netherlands, 2020. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong, Pool)/1973 file photo, President Richard Nixon speaks during White House news briefing in Washington. (AP Photo/Henry Burroughs.)/ Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan in September 1980. (AP Photo/NewsBase)/Republican presidential candidate former President Donald Trump attends a campaign rally at Charleston Area Convention Center in North Charleston, S.C., Wednesday, Feb. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/David Yeazell)

Asking the U.S. Supreme Court to deny Donald Trump‘s attempt to stop his criminal election subversion conspiracy trial in Washington, D.C., special counsel Jack Smith argued that not only is Trump’s so-called “presidential immunity” argument unsupported by caselaw with “deep roots” going back more than a century, but his premise also ignores how some of Trump’s own right-wing idols, like former presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, were treated under the law.

In the run-up to this showdown at the nation’s high court, Trump’s lawyers have argued that former and current U.S. presidents are “unexaminable,” by the courts, “absolutely” immune from criminal prosecution and, as special counsel Jack Smith put it to the U.S. Supreme Court late Wednesday night, seemingly permitted to receive a “blank check” for alleged criminal activity.

Trump contends that any treatment of the high office otherwise could impugn the powers of the presidency itself and make it impossible — or close to it — to govern without fear that presidents in the future will not be cowed by their opponent’s threats of “unfounded indictments,” Smith wrote Wednesday.

Yet that position glaringly overlooks key pieces of American history Trump might find relevant.

“For instance, former President Reagan was subject to criminal investigation for Iran/Contra, with the responsible federal prosecutor determining that the evidence did not warrant prosecution,” Smith wrote.

The Office of Independent Counsel investigating Iran/Contra was led by Lawrence Walsh, a lifelong Republican and former federal judge who was appointed to the bench by President Dwight Eisenhower, also a Republican. Walsh also worked under Nixon as a peace negotiator for a period, a 2014 profile from Politico notes.

At the end of his report, Walsh concluded Regan would not be criminally prosecuted. Not that he could not be criminally prosecuted.

“But because a president, and certainly a past president, is subject to prosecution in appropriate cases, the conduct of President Reagan in the Iran/Contra matter was reviewed by Independent Counsel against the applicable statutes. It was concluded that President Reagan’s conduct fell short of criminality which could be successfully prosecuted,” the 1993 final report stated.

Smith noted too that longtime Republican and former Attorney General Bill Barr, whom Trump once saw fit to appoint to the powerful role, declared in May 2020 that he did not expect criminal charges would be brought against former President Barack Obama despite Trump’s public clamoring for his incarceration at the time.

“People should be going to jail for this stuff,” Trump said, according to a Washington Post report cited by the special counsel in Wednesday’s brief.

Another one of Trump’s heroes central to the government’s brief is Richard Nixon, better known for disgracing the presidency with the Watergate scandal than his lengthy pen pal relationship with Trump in the 1980s.

And yet despite a decades-long affinity, Trump and his lawyers appear willing to disregard the lessons, and moreover, the caselaw, imparted in U.S. v. Nixon and Nixon v. Fitzgerald.

In Fitzgerald, the high court found that a balance existed between “the constitutional weight of the interest to be served against the dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch,” Smith wrote.

In United States v. Nixon, the idea was similar.

There the court weighed the interests of the executive branch as it pertained to confidential communications against “the primary constitutional duty of the Judicial Branch to do justice in criminal prosecutions,” Smith noted.

The rest was history and the court ruled unanimously that a president does not have executive privilege in immunity from subpoenas or other civil court actions.

Even after Watergate and with the “succession of independent counsels and special counsels” that followed, Smith argued, the suggestion that a former president has total immunity from federal criminal prosecution “finds little mention in any source before applicant’s briefs in this case.”

The special counsel reminded the justices:

The recognition that civil immunity does not imply criminal immunity for these officials has deep roots in the law. E.g., Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 348 (1879).

And exposure to criminal liability is one of the justifications for civil immunity; despite immunity from private civil damages actions, criminal prosecutions exist to deter and provide accountability for crimes.

This Court has thus “never held that the performance of the duties of judicial, legislative, or executive officers, requires or contemplates the immunization of otherwise criminal deprivation of constitutional rights.” O’Shea v. Littleton, 414 U.S. 488, 503 (1974).

“On the contrary, the judicially fashioned doctrine of official immunity does not reach ‘so far as to immunize criminal conduct proscribed by an Act of Congress.’” Ibid. (quoting Gravel v. United States, 408 U.S. 606, 627 (1972).

Trump’s argument that he cannot be criminally prosecuted either because he was already acquitted of similar charges through impeachment by Congress also fails to hold up, according to Smith.

Justices wrote in U.S. v Nixon that “[A President] can be indicted after he leaves office at the end of his term or after being ‘convicted’ by the Senate in an impeachment proceeding.”

“Applicant makes no effort to square his position with that established view,” Smith wrote.

Trump’s lawyers do make the point for prosecutors that their “chilling” theory is moot, however, he argues.

“During the Nixon Presidency, misconduct in the White House intended to harm political rivals and keep the Administration in power led to a criminal investigation, federal indictment of the Watergate conspirators, and the naming of then-President Nixon as an unindicted co-conspirator and his subsequent acceptance of a pardon for all criminal offenses arising from his conduct,” Smith wrote. “Yet no later prosecutions of former Presidents ensued — until applicant’s indictment 50 years later for allegedly seeking to thwart the political process and perpetuate himself in power.”

The nation’s tradition is clear before the Supreme Court, the special counsel argued.

“Presidential conduct that violates the criminal law to achieve the end of remaining in power may be subject to a prosecution. That possibility should not chill legitimate Presidential

conduct,” he wrote.

Multiple lower courts have rejected Trump’s theory that criminal prosecution can only occur after impeachment and conviction. The theory was rejected — somewhat ironically — in another case involving a different Nixon, federal judge Walter Nixon Jr.

In Nixon v. United States, it was a rare instance of criminal prosecution and impeachment proceedings being involved simultaneously.

Walter Nixon Jr.’s case doused Trump’s “impeachment-first” theory, Smith wrote, before also suggesting that the former president’s defense team was imposing a “tortured” interpretation of case law:

If applicant’s interpretation were correct, all federal officers, not just the President, would have to be impeached and convicted before prosecution. But history reflects a clear separation between the two constitutionally distinct procedures. Although scores of federal officers have been criminally prosecuted throughout our history, fewer than two dozen officers have ever been impeached by the House, with only eight — all federal judges — convicted in the Senate. And in the few cases in which both procedures have been invoked, prosecution has regularly preceded impeachment.

The Justice Department rejected that an impeachment acquittal bars criminal prosecution in a 2000 Office of Legal Counsel opinion from then-assistant Attorney General Randolph Moss.

Significant as well in Smith’s argument is his citing of Trump to himself.

“The Framers did not provide any explicit textual source of

immunity to the President,” Smith wrote. “‘The text of the Constitution explicitly addresses the privileges of some federal officials, but it does not afford the President absolute immunity.’ Appl. App. 44A (quoting Trump v. Vance, 140 S. Ct. 2412, 2434 (2020) (Thomas, J., dissenting)).”

To resolve this question promptly, Smith urged the court to get down to business and treat the request for a stay as a petition to the court for oral arguments.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]