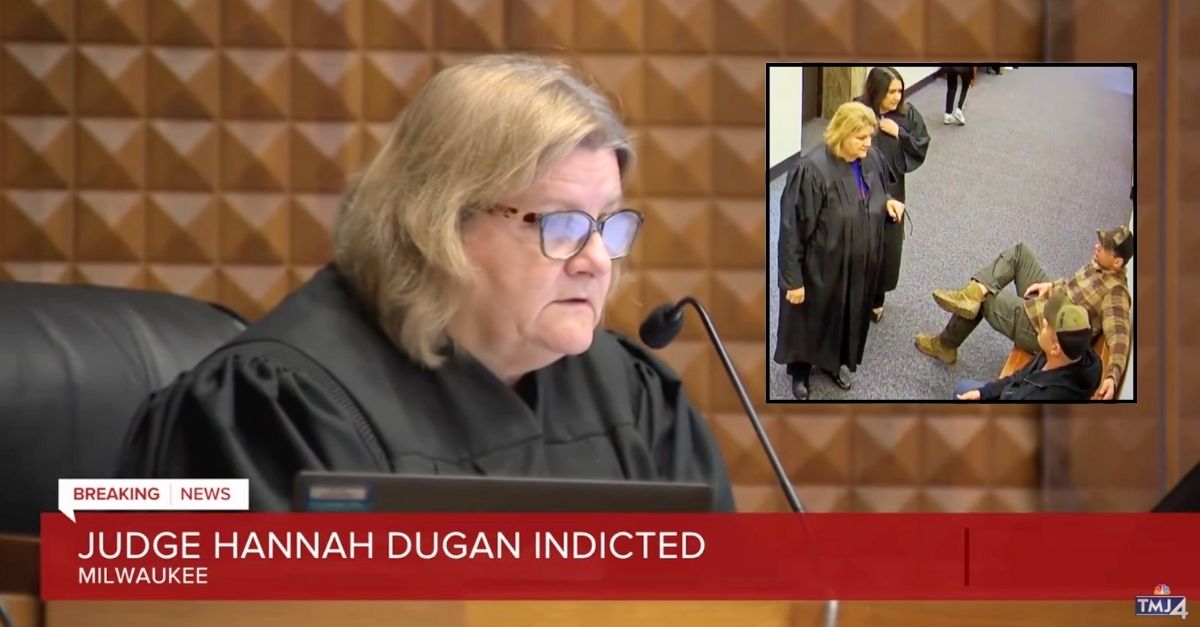

Background: Milwaukee County Judge Hannah Dugan in court (WTMJ/YouTube). Inset: Surveillance video shows Milwaukee County Judge Hannah Dugan speaking with ICE agents before Eduardo Flores-Ruiz’s detainment (WDJT/YouTube).

Prosecutors and defense attorneys for Hannah Dugan, the Wisconsin judge indicted on federal charges for allegedly impeding ICE agents during an immigration bust, have traded legal blows over whether her case should proceed — with Dugan’s side condemning her prosecution as “far-fetched,” while the federal government claims she is using “amorphous and contestable distinctions” to prop up her arguments.

Dugan, 66, was indicted earlier this year for allegedly helping an undocumented immigrant evade federal officers shortly after he appeared in her Milwaukee County Circuit courtroom in connection with a domestic abuse case. She filed a motion in May seeking to have the federal obstruction charges she’s facing thrown out, arguing that — much in the way that the president is immune from prosecution for official acts while in office — she too is the beneficiary of broad judicial immunity.

Since then, prosecutors and defense attorneys have made various arguments in regard to why the case should be dismissed or proceed. Dugan’s team hit the government with a 30-page filing on July 15, saying she was being prosecuted “for doing her job, not in the way that some federal agents preferred, true, but her job all the same.” The Justice Department responded Tuesday with a 30-page filing of its own, which rebuked Dugan’s claims and skewered her for explaining them in a “gerrymandered way,” per the DOJ.

“Dugan’s assumption of immunity wrongly inverts the analysis on a motion to dismiss charges that are properly pled in an indictment,” federal prosecutors said. “Even in her view, criminal prosecutions of state judges are undisputedly permitted in certain circumstances. However, this does not in any way imply the creation of categories where prosecutions are forbidden in other circumstances.”

According to the DOJ, Dugan is “simply attempting to explain away the historical prosecution of judges” in a way that relies on “amorphous and contestable distinctions to carve her case out.”

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

In their July 15 filing, Dugan’s attorneys claimed that if the case proceeded, state and federal judges would be “vulnerable” to prosecution by the federal executive “any time they handle a trial involving contraband in evidence or schedule a hearing in ways that inconvenience — and thus arguably impede — federal officers,” according to the filing.

Central to her arguments, per the DOJ, is the “misconception” that Dugan is charged for committing “official acts in the course of her ordinary duties” as a “state judge,” and she was doing “her job” and “nothing more.” Dugan’s lawyers say the government has now opened the door for criminal charges to be filed in relation to court tasks and certain procedures, such as showing evidence at trial.

“A judge handling a child pornography case or a drug case, with either child pornography images or controlled substances passed around as evidence in court (that is, possessed and distributed), would be at the mercy of federal law enforcement,” the lawyers charged. “So would any state or federal judge scheduling a hearing or holding over an undocumented accused, victim, or material witness in ways that irritate or slow federal officers hoping to arrest or remove the undocumented person with a crucial role in the case.”

Writing in a footnote, Dugan’s team admitted that “some of these examples seem far-fetched,” per the filing.

“So did this prosecution until it happened,” they proclaimed.

“The Court can avoid definitively resolving these constitutional questions by recognizing that the statutes at issue here do not reach the conduct alleged,” Dugan’s lawyers added. “There are countless ways to obstruct justice or harbor a fugitive that do not involve the exercise of state judicial power. There is no reason to think that the Congress that enacted these statutes thought it was empowering federal agents to arrest and prosecute state judges for official acts.”

Prosecutors argued in their filing Tuesday that “if it were in fact true” that judges enjoy general judicial immunity subject to certain defined legal exceptions, a court would have said so at some point. “Quite simply, the Supreme Court has never retreated from its observation that judicial immunity does not apply in criminal cases,” the DOJ said. “Rather, the dividing line is whether the conduct fits the elements of a criminal statute.”

Earlier this month, U.S. Magistrate Judge Nancy Joseph in the Eastern District of Wisconsin issued a recommendation to U.S. District Judge Lynn Adelman, the judge presiding over Dugan’s case, that said while judges are largely immune in civil cases for their official actions, no such judicial immunity exists when one is criminally charged. Prosecutors said Tuesday they believed Joseph’s recommendation was correct and that Dugan’s objection would not provide a “sound reason” to dismiss her indictment now.

“Accepting her claim about the nature of her prosecution would require fact-finding, which is untenable on a motion to dismiss, a principle that the magistrate judge followed and to which Dugan has not objected,” the DOJ said.

“Under Dugan’s framework, in which complete judicial immunity from criminal law is needed to protect judges from prosecution in these every-day scenarios, the rest of the operatives in the criminal justice system, from jurors to government analysts to law enforcement officers to undercover agents, would be left subject to criminal charges for attending to their duties,” the prosecutors added. “But that is not the way the criminal justice system operates. Recognizing the common-sense proposition that operatives in the criminal justice system do not violate the criminal law on mere proof, without more, that they are in good faith carrying out their required duties, does not translate into a need to recognize blanket judicial immunity for all acts done under the guise of a judge’s duties.”

Conrad Hoyt contributed to this report.