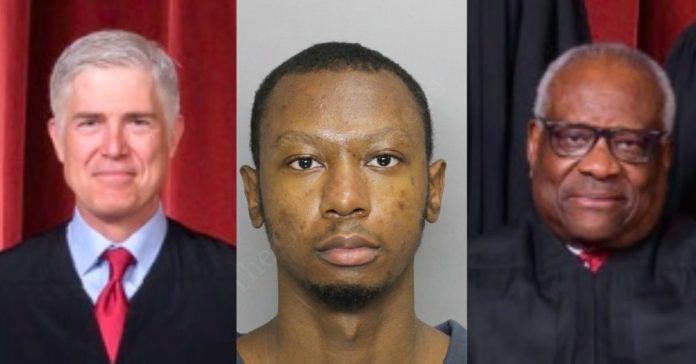

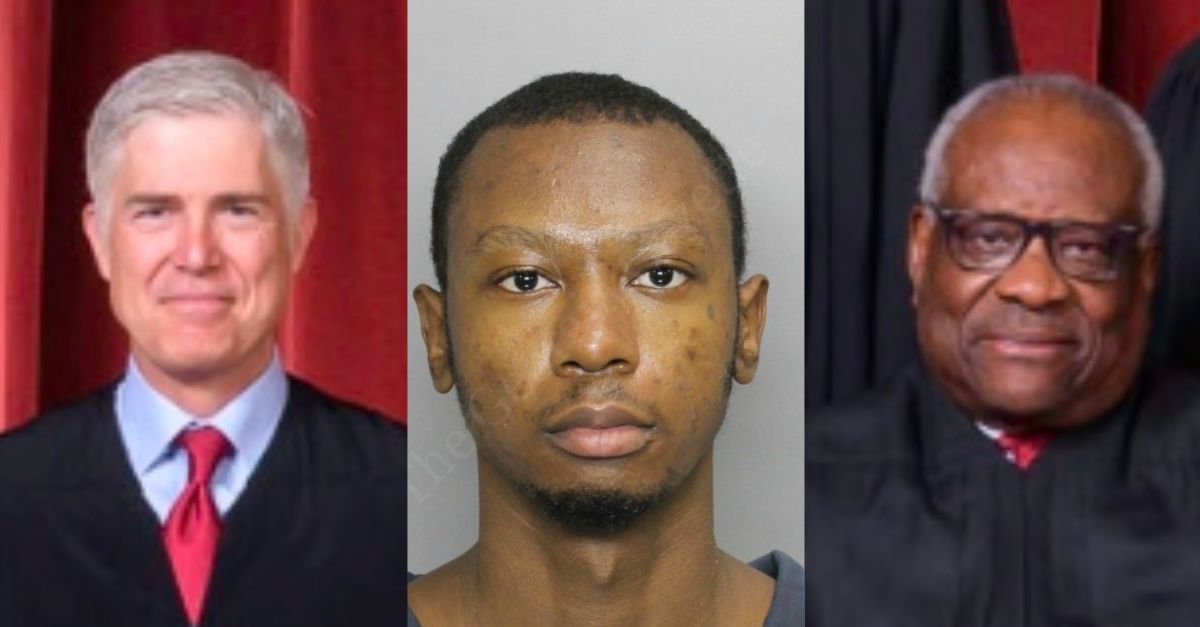

Left, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Neil Gorsuch; Right: Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Clarence Thomas (Photograph by Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States); Center: Damian McElrath (Photograph, Cobb County Sheriff’s Office).

The U.S. Supreme Court continued its term Tuesday with oral arguments in a case involving double jeopardy, mental illness, murder, and the state of Georgia.

In the case of McElrath v. Georgia, the justices will decide whether Georgia’s prohibition against successive prosecutions means that prosecutors can retry a mentally ill man who was found both guilty and not guilty of the same alleged murder.

The difference comes down to what mental state is required for each murder charge filed in the case.

Damian McElrath, then 18, stabbed his adoptive mother, Diane McElrath, to death in 2012.

After trial, a jury found McElrath not guilty of “malice murder” by reason of insanity. In Georgia, malice murder is the most serious murder charge, roughly parallel to a first-degree murder charge in many other states. It requires that the offender intentionally killed a victim.

The same jury, however, also returned a simultaneous verdict at the end of the trial that McElrath was guilty but mentally ill on charges of felony murder and aggravated assault. The felony murder rule allows prosecutors to charge defendants with murder even when a defendant did not directly cause a victim’s death. In Georgia, as in most states, felony murder is a less serious charge than malice (or first-degree) murder.

Either verdict might make sense on its own, as different mental states are required for the two crimes. However, as lawyers for McElrath noted before the Supreme Court on Tuesday, it is not not possible for a person to be both legally sane and legally insane at the same time during the commission of the same act.

Likely, the inconsistent outcomes were the result of the jury’s wanting to return a verdict for an offense less serious than malice murder.

However, because the verdicts conflicted with one another, the trial court pronounced them “repugnant” under Georgia’s statute and vacated both verdicts, and allowed a second trial. It is that second trial against which McElrath, through his attorneys, now fights.

McElrath’s argument is that the jury’s finding of not guilty by reason of insanity constitutes an acquittal, and that Georgia is thereafter prohibited from retrying McElrath for the same crime. The Georgia Constitution guarantees a right against double jeopardy that mirrors the federal guarantee, that “[n]o person shall be put in jeopardy of life or liberty more than once for the same offense except when a new trial has been granted after conviction or in case of mistrial.”

Georgia contends that the dueling verdicts are not really verdicts at all, but that they amount to no more than intermediate steps in the trial process. Moreover, Georgia says, the right to define what’s what within its own criminal system belongs to it as part of state sovereignty. Therefore, the Peach State says, double jeopardy does not attach.

The McElrath case reaches the justices via appeal from the Supreme Court of Georgia, which agreed with the trial court that the verdicts were “repugnant,” and held, “Put simply, we determined, based on the evidence presented at trial, that it was not legally possible for McElrath to simultaneously be both sane (guilty but mentally ill) and insane (not guilty by reason of insanity) during the single episode of stabbing his mother.”

The Georgia Supreme Court acknowledged that individuals have the right to be free from successive prosecutions or punishments for the same crime, and that even the same issue cannot be relitigated once a final judgment on the merits is reached. However, it denied that the rule applied in McElrath’s case. The jury’s conflicting findings were “valueless,” said the court.

“There is no way to decipher what factual finding or determination they represent, and McElrath cannot be said with any confidence to have been found not guilty based on insanity any more than it can be said that the jury made a finding of sanity and guilt with regard to the same conduct,” wrote Justice Charles Jones Bethel for the court.

The justices of the U.S. Supreme Court are now reviewing the Georgia court’s finding, and heard oral arguments on Tuesday.

When attorney Richard Simpson argued on behalf of McElrath, the justices posed multiple questions centered on Georgia’s right as a sovereign state to define its criminal procedure the way it chooses. Chief Justice John Roberts compared McElrath’s case to one in which a jury failed to follow procedural rules requiring a signed verdict sheet.

Simpson said that a state would be free to enforce such a procedural requirement that might prevent a verdict from actually being pronounced; Simpson said such a scenario differed from McElrath’s case in that the Georgia court simply declared the McElrath verdict void after it was rendered based on its conflict with the second verdict. Once a not-guilty verdict was reached, said Simpson, the right against double jeopardy was triggered.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson then shifted the focus to past cases in which federal, not state, authorities were the ultimate determiners of acquittals for purposes of double jeopardy, offering, “I had understood [the determination of whether something is an acquittal] to be a federal question.”

When Georgia Solicitor General Stephen Petrany took the podium for the state, he argued that despite McElrath’s assumptions, there simply was no verdict in his case. Under Georgia law, Petrany said, a jury cannot render a verdict by giving “incoherent, contradictory statements” that “do not resolve the factual inquiry.”

Justice Clarence Thomas, a Georgia native, pressed Petrany on the state’s logic and asked why either verdict would have been sufficient its own while both together are “not verdicts” per Georgia’s argument.

Thomas commented, “I don’t know how you get around the notion that before [the verdict is voided for repugnancy], there actually is a verdict.”

Petrany disagreed, holding firm to his position that “there was never a verdict,” because the jury was “speaking out of both sides of its mouth” and declaring McElrath “both sane and insane at the same time.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch referred Petrany to the laws of other states, none of which have statutes that create the kind of legal conundrum at issue in the McElrath case. Gorsuch delivered something of a soliloquy about the relative untouchability of acquittals by the judiciary:

Shouldn’t that tell us something? That for 230 years in this country’s history, we have respected acquittals without looking into their substance and without looking into how they fit with other counts and said that a jury is a check on judges. It’s a check on prosecutors. It’s a check on overreach and a check on our democratic system. And we do not ever talk about whether they make sense to us. They may be products of compromise. They may be inconsistent with verdicts on other counts. We don’t question them. This is the first time this issue has arisen here. Shouldn’t that tell us something?

Kagan, a former prosecutor, followed up with case law that continued to conflict with Georgia’s position. Kagan said that the Court, in “numerous cases,” “rejected out of hand” the idea that a state could pass a law declaring that inconsistent verdicts by a jury would constitute no verdict at all.

The McElrath case is not the first time Gorsuch has been skeptical about any narrowing of double jeopardy guarantees. In June 2022, Gorsuch penned a dissent joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan in another double jeopardy case. Gorsuch bluntly summed up the relevant considerations: “Same defendant, same crime, same prosecuting authority.”

Thomas has shown uncharacteristically pragmatic thinking in cases involving double jeopardy, even acknowledging in a 2019 ruling that modern cases raise double jeopardy questions that were likely not even considered 200 years ago. Thomas also specifically commended Gorsuch on his double jeopardy analysis in that case.

You can listen to the full oral arguments in McElrath v. Georgia here.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]