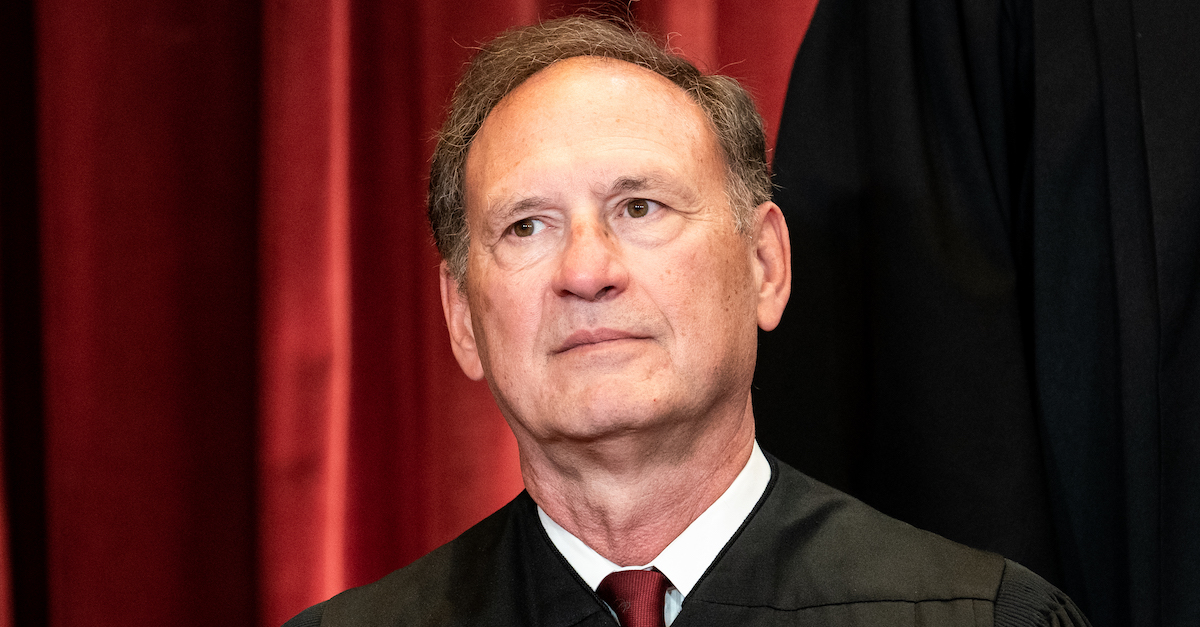

WASHINGTON, DC – APRIL 23: Associate Justice Samuel Alito sits during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

The justices of the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case of Muldrow v. St. Louis on Wednesday. The case asks whether a Missouri police sergeant was the victim of sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 when she was involuntarily transferred from an intelligence role to a patrol position because her supervisor preferred a man for her job.

Title VII only bars employment decisions as illegally discriminatory if those decision cause a significant disadvantage for the employee. Though an employee may prefer one role over another, that preference is not quite the same thing as a “disadvantage” for civil rights purposes.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit made up of U.S. Circuit Judges James B. Loken, a George H.W. Bush appointee, Bobby Shepherd, a George W. Bush appointee, and David Stras, a Donald Trump appointee, sided with the police department.

Jatonya Muldrow, a sergeant with the St. Louis Police Department, filed a lawsuit against the department, alleging that she was the victim of sex discrimination because she was involuntarily transferred from her position in the department’s Intelligence Division to a patrol position because her supervisor wanted to hire a man for her job.

While at the Intelligence Division, Muldrow worked on public corruption and human trafficking cases, served as head of the Gun Crimes Intelligence Unit, and oversaw the Gang Unit. She worked Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. or 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Muldrow was also deputized as a Task Force Officer by the FBI for its Human Trafficking Unit, which meant she had the same privileges as other FBI agents, including access to FBI field offices and databases, the opportunity to work in plainclothes, access to an unmarked FBI vehicle, authority to conduct human trafficking-related investigations outside of the St. Louis city limits, and the opportunity to earn up to $17,500 in annual overtime pay.

In 2017, Muldrow’s new supervisor made multiple personnel changes which included reassigning Muldrow to the Fifth District where she became responsible for administrative and supervisory duties of patrol officers, arrests, and reported crimes. In her new role, Muldrow was required to work a rotating schedule that included weekends, wear a police uniform and drive a marked police vehicle, and work within a controlled patrol area. She earned the same salary, but was no longer eligible for the FBI’s overtime pay. However, other overtime opportunities were available to her.

Under Title VII, it is illegal for an employer to “fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment,” because of protected characteristics such as race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Loken wrote for the panel of the Eighth Circuit and said that Muldrow’s deposition testimony that the work at her new position “was was more administrative and less prestigious than that of the Intelligence Division” was not persuasive without more evidence. Loken noted that Muldrow only spent eight months in the Fifth District, and the brief reassignment “did not harm her future career prospects.” The appellate court upheld the trial court’s ruling that the defendant police department was entitled to summary judgment in its favor.

On appeal, the justices are not considering whether Muldrow was actually fired because she is a woman, as that would be a matter for the finder of fact to decide after hearing evidence at trial. Rather, they are reviewing the summary judgment ruling to decide whether, as a matter of law, Title VII considers a transfer to be the kind of adverse employment action that would give rise to a civil claim if it were done on the basis of a protected characteristic such as sex.

During over 90 minutes of oral argument, the justices spent the bulk of argument time devoted to the question of whether Title VII requires an articulable injury or whether discrimination — that is, the disparate treating of a particular group — is an injury in itself.

Some of the conservative justices seemed quite opposed to any rule that a simple difference in treatment should be actionable on its own without a more concrete injury — rather an inconsistent position set against the Court’s recent ruling in the affirmative action admissions cases.

Last June, the Supreme Court held that affirmative action policies in college admissions constituted illegal race-based discrimination. Although the disparate treatment may have been carried out in an effort to foster diversity, “Eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it,” said Chief Justice John Roberts.

Logically in line with that ruling, attorney Brian Wolfeman argued for Muldrow that treating someone “differently” is the same as treating someone “disadvantageously” when person is a protected class, because discrimination itself is injurious.

Some of the justices, however, seemed unconvinced that disparate treatment in the employment context was as problematic as disparate treatment in an affirmative action context.

Roberts tossed out a hypothetical involving coworkers of different sexes being placed in offices painted different colors or with different views.

Justice Samuel Alito said that although disparate treatment on the basis of a protected characteristic is “wrong,” that some sort of minimum threshold requirement for court action could be appropriate.

Without such a threshold, Alito said, the door would be open for employees to sue under Title VII for if a boss were to regularly ask one coworker, but not another, whether they had a nice weekend. The justice said that the case was not about whether there are “benign” forms of discrimination, but rather, whether discrimination with only “de minimus” effects really belongs in federal court.

Alito said a second time, “all discrimination is morally wrong.”

Justice Elena Kagan, however, challenged Alito’s blanket statement asking if there were not some differences and distinctions in treatment that could make those with protected characteristics better off.

During his colloquy with Assistant to the Solicitor General Aimee Brown (who supported Muldrow’s petition on behalf of the Biden administration), Alito raised concerns about overrunning federal court dockets with hundreds of discrimination claims over what he called “trivial disparate treatment.” Alito said his concern was not about what’s “moral and immoral,” but rather, about “what belongs in federal court,” and about the desire to permit federal judges some discretion to dismiss trivial cases at an early stage in litigation.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who had slammed the Court’s affirmative action decision as being “without any basis in law, history, logic, or justice,” and grounded in “let-them-eat-cake obliviousness,” asked about the need and usefulness of any requirement that there be a threshold injury. Jackson asked whether the nature and extent of a victim’s injury could not be more appropriately addressed at the damages phase of a lawsuit — rather than as an element of the claim. In such a framework, a victim of so-called “de minimus” discrimination would still have a legal claim, but would be awarded minimal damages.

Jackson also argued that “every defendant” would argue that because a person passed over on the basis of a protected characteristic “went on to do great things,” that the person had not been harmed at all.

Justice Clarence Thomas, long a fierce opponent of affirmative action, asked about a hypothetical police department that decided it had a legitimate need to transfer Black or Hispanic officers to a certain precinct.

“So simply making the selection or the transfer based on race or sex in and itself becomes actionable?” Thomas asked Brown.

When attorney Robert Loeb argued on behalf of the police department, Justice Sonia Sotomayor brought the questioning around to the practical impact of the discrimination at hand.

“I have a very hard time understanding how a court could ever see that switching someone’s schedules isn’t enough of an injury,” Sotomayor said.

In March 2021, Muldrow was charged by local authorities with misdemeanor witness tampering after being accused of attempting to dissuade another officer from reporting a sexual assault that allegedly occurred in 2009. Prosecutors alleged that Muldrow characterized the reported assault as “just a misunderstanding.”

Ultimately, police determined that there had been no credible allegation of sexual assault and the related misdemeanor charges against Muldrow were dismissed because prosecutors filed them one day after the statute of limitations had expired.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]