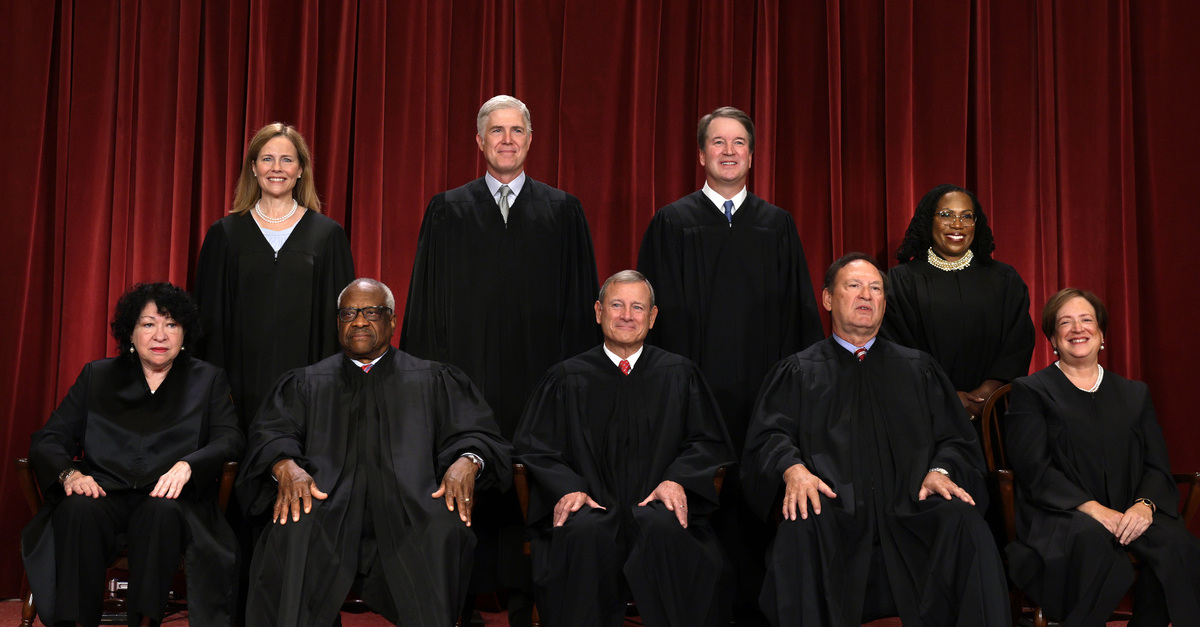

WASHINGTON, DC – OCTOBER 07: United States Supreme Court (front row L-R) Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan, (back row L-R) Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pose for their official portrait at the East Conference Room of the Supreme Court building on October 7, 2022 in Washington, DC. (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

The Supreme Court of the United States adopted an official and long-awaited Code of Conduct for Justices Monday, just weeks after Justice Amy Coney Barrett publicly said that all nine justices considered an ethics code “a good idea.”

Although the 14-page code details a number of ethical expectations, it conspicuously excludes any mention of enforcement mechanism or penalty for violation. The legal community appears divided over the significance of the omission; while some fault the justices for making much ado about a lamentably impotent set of ethics standards, others say that a more forceful enforcement mechanism would be constitutionally impossible.

As the justices noted in their introductory statement, many of the code’s requirements are “not new,” and mirrored ethics rules from other sources including those that apply to other members of the federal judiciary.

They further explained that their decision to issue a formal code of conduct was an attempt to correct a recent “misunderstanding” that the justices operated “unrestricted by any ethics rules.” The code, they explained, was merely an accounting of the standards to which they have already been holding themselves.

More specifically, the code requires that justices uphold the independence of the federal judiciary, avoid all forms of impropriety and outside influence, operate without bias or fear of criticism, recuse themselves in cases to which they are personally connected, avoid engaging in activities that “detract from the dignity” of official duties, and refrain from engaging in political activity.

All nine justices signed on to the new code.

Reactions to the Court’s release of the code were, as could reasonably be predicted, swift and fierce. The most common criticism, voiced by many lawyers, was that the code conspicuously lacks any enforcement mechanism.

University of Texas School of Professor Steve Vladeck observed that, “Nothing in the 14-page document, or the one-page cover note, addresses the elephant in the room: *Whatever* rules the justices *say* they are bound to follow, *who* is going to enforce those rules—and how?”

Similarly, Fix the Court’s Gabe Roth released a statement slamming the justices for “clearly and for years fail[ing] to live up to their ethical responsibilities,” and pronouncing the Code as one which “leave[s] much to be desired.”

“If the nine are going to release an ethics code with no enforcement mechanism and remain the only police of the nine, then how can the public trust they’re going to do anything more than simply cover for one another, ethics be damned?” asked Roth, who also specifically noted that the Code’s use of the word “knowingly” appeared to signal an excuse of Justice Clarence Thomas’ dealings with Harlan Crow.

Likewise, Georgia State Constitutional law professor at Georgia State University College of Law Anthony Michael Kreis said, “A Code of Conduct with no meaningful enforcement mechanism is a mere gesture.”

Anthony Coley, former Head of Public Affairs of the U.S. Justice Department under Barack Obama, slammed the code for having “no teeth.”

“It’s silent on the most important question: When a Justice violates it, then what?” asked Coley.

However, Constitutional expert and former Antonin Scalia clerk Ed Whelan argued that the absence of a specific enforcement mechanism is “a necessary imperfection in the system” and that proposals to correct that imperfection “would likely create more problems than they would solve.” Whelan’s comments quoted partially from a 2021 official report made by Brookings Institution Research Fellow and former Deputy Director of the Federal Judicial Center Russell R. Wheeler to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States.

In Wheeler’s report, he specifically addressed the question of whether Congress should create a mechanism by which other judges would investigate and sanction misconduct by Supreme Court justices. Wheeler concluded that the answer was a blunt “no.” Wheeler detailed the road to his conclusion: if Congress were to create a disciplinary mechanism, most — or perhaps the only— plausible people to staff it would be lower court judges or retired justices. That would be a problem, said Wheeler, because lower court judges, “simply have no legitimate role in the administration of the Supreme Court,” specifically due to the fact that lower courts were created by Congress while SCOTUS was created directly by the Constitution.

Furthermore, said Wheeler, an official enforcement body could “weaponize a judicial conduct complaint procedure for the justices, drawing in not only the justices but also those who appoint the panel.” Under such a system, Wheeler noted, complaints might become the favored response to misconduct, simply because impeachment is more cumbersome. Moreover, a small bureaucracy would need creation to handle what would likely be a flood of complaints, though “almost all of them frivolous,” given comparable data.

Vladeck and Whelan went back and forth several times online with Vladeck pointing to a suggestion he raised in October. Vladeck advocated for the appointment of an Article III Inspector General who would monitor compliance with ethics rules, and discipline employees who are not Article III judges, recommend disciplinary action against lower court judges, and report misconduct by Supreme Court justices directly to Congress.

Whelan, in turn, pointed out that Vladeck’s proposed solution was action by Congress and not the Court itself, to which Vladeck responded, “Sure, but if the justices were truly committed to putting teeth into these new rules, they could certainly work with Congress—or, at the very least, note the possibility of such a mechanism.”

In recent months, calls for ethics checks on Supreme Court justices reached something of a climax. In late October, the Senate Judiciary Committee posted on X, previously known as Twitter, that a “[n]ew report finds that Justice Clarence Thomas failed to disclose $250,000+ of loan forgiveness for an RV, lent to him by a wealthy health care industry benefactor.”

Last July, the Senate Judiciary Committee passed a measure that would subject Supreme Court justices to stricter standards, increased public scrutiny, and a dedicated investigative board for misconduct allegations. Though Senate Judiciary Chair Dick Durbin, D-Ill., hailed the the bill as “a crucial first step in restoring confidence in the Court,” Senate Republicans declared the measure “dead as fried chicken.”

Of course, Supreme Court justices — like other members of the federal judiciary — can be removed through the impeachment process for misconduct. Indeed, as allegations against Thomas have mounted, some have suggested his impeachment. However, despite the theoretical possibility of impeachment, only one justice has ever been impeached. Associate Justice and note Federalist Samuel Chase was impeached in 1804 after the House of Representatives passed Articles of Impeachment against him for allowing partisan loyalty affect his court decisions. However, Chase was acquitted the following year by the Senate and remained in office.

You can read the full Code of Conduct for Justices here.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]