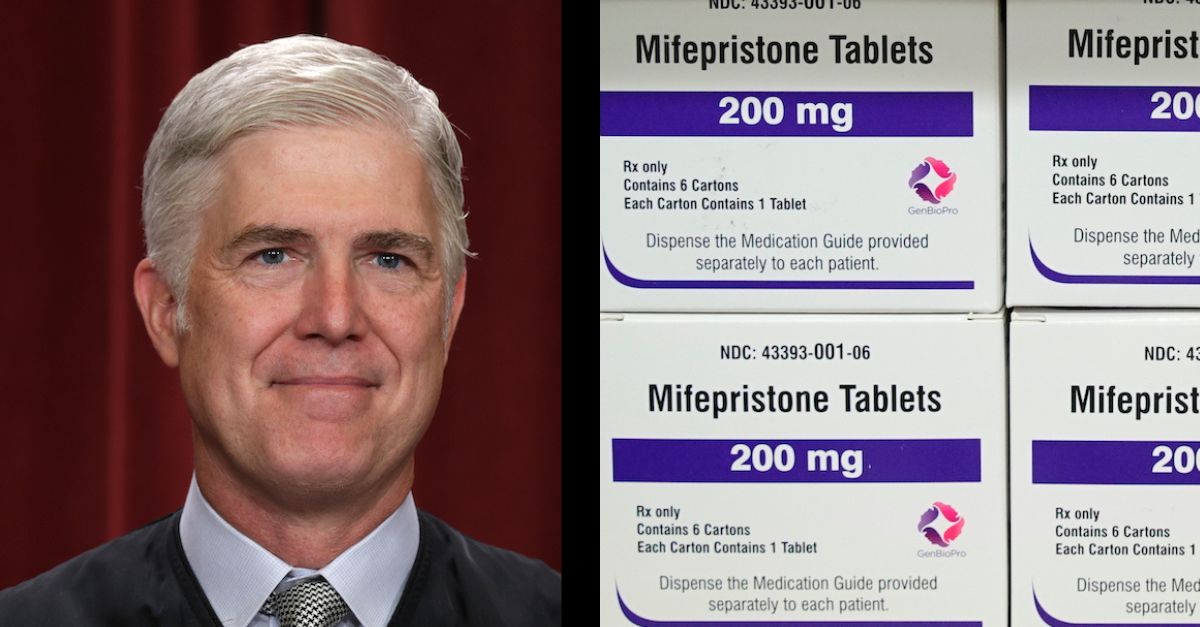

Left: Justice Neil Gorsuch poses for an official portrait in the East Conference Room of the Supreme Court building on October 7, 2022 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images). Right: Boxes of the drug mifepristone sit on a shelf at the West Alabama Women’s Center in Tuscaloosa, Ala., on March 16, 2022 (AP Photo/Allen G. Breed, File).

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine on Tuesday — a case centered around a commonly-used abortion drug that threatens widespread consequences for the entire drug industry.

The justices focused nearly the entirety of the proceedings on whether the plaintiffs in the case — a group of anti-abortion doctors who claimed the drug should be taken off the market because of how it affects them, not people who have taken the drug — have an appropriate claim to bring before the judiciary. The plaintiffs’ argument is a novel one, and should the Supreme Court rule in their favor, the decision has potential to affect much more than just abortion pills.

However, the bench did not appear warm to the idea of siding with the doctors in their crusade against the medication, and Justices Neil Gorsuch and Ketanji Brown Jackson emerged as a pair of unlikely bedfellows as they expressed the same overt skepticism about the doctors’ claims against the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

A decades-old approval, an unprecedented decision, and broad consequences

The FDA approved mifepristone in 2000; the drug is one part of a two-drug combination used in the U.S. for medication abortions. Misoprostol, the second drug used as part of the regimen, also has uses unrelated to the termination of pregnancy.

At the center of the dispute lies an unprecedented decision by U.S. District Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk in which Kacsmaryk, a Donald Trump appointee, single-handedly ordered the FDA to revoke its approval of mifepristone. The ruling was the result of a lawsuit, likely strategically filed for the purpose of reaching Kacsmaryk, by the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (AHM) in which it claimed that the FDA’s approval should be revoked because the drug is unsafe.

After a lengthy hearing on the drug’s safety, Kacsmaryk issued the order AHM requested. The Biden administration appealed and argued that allowing a judge to second-guess the FDA’s scientific judgment is dangerous for women. More than 250 members of Congress support the administration’s position, and filed an amicus brief explaining that when it authorized the FDA to approve drugs, “it did not invite federal courts to substitute their judgment for the expert conclusions of FDA’s scientists.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit ruled on appeal that it was too late for the doctors and medical groups to challenge the 2000 approval of mifepristone, but kept part of Kacsmaryk’s order in place, resulting in decreased access to the drug. The justices will now review both Kacsmaryk’s underlying order and the Fifth Circuit’s decision.

The case has major implications that go far beyond the context of abortion. Should the justices rule to uphold Kacsmaryk’s first-of-its-kind decision to demand the FDA roll back a decades-old drug approval, it could set the precedent that other judges could similarly interfere with approval of any and all drugs.

A key procedural requirement takes center stage

The justices have already dealt with the case on an emergency basis and issued a temporary order that allowed mifepristone to remain widely available while the challenge to its approvals continued. However, Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito indicated that they would have ruled differently.

The primary legal issue in the case is that of standing — the requirement under Article III of the Constitution that every plaintiff in a justiciable case suffer an actual concrete injury or certain impending injury that goes beyond the mere hypothetical.

The AHM mifepristone plaintiffs are a group of anti-abortion doctors, and not patients who have taken the drug. These doctors argued that their quality of life was harmed because it was “emotionally taxing” for them to treat women who had taken mifepristone to terminate a pregnancy. According to the plaintiff doctors, some of these unfortunate patients suffered “torrential bleeding,” which was upsetting for the doctors to witness. These unwanted emotional consequences are what the doctors claimed was the injury that created their right to sue.

Additionally, they argued that other doctors — although not they themselves — were forced to perform surgical abortions after patients experienced complications from taking mifepristone, and that doing so went against those doctors’ personal beliefs.

The FDA’s label for the drug shows that between 0.04-0.6% of users in three studies were hospitalized after taking the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol.

Danco, the company that manufactures mifepristone, argued in its brief that if the justices agree that these doctors have standing to sue, it would risk “virtually every government regulation that touches on health or safety.” Not only could doctors argue against approval of every drug, but teachers could challenge regulations that allegedly disrupt their classrooms, for example, and firefighters could upend regulations they claim present fire risks.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar argued Tuesday that there is a “profound mismatch” between the injury the plaintiff doctors claim and the relief they are asking the justices to provide, and her argument found a particularly receptive audience in Gorsuch and Jackson.

The Court’s most outspoken foe of administrative agencies essentially goes to bat for the FDA

Although the current Supreme Court generally — and Gorsuch specifically — has proven hostile to federal administrative agencies, Gorsuch emerged from oral arguments as an outspoken skeptic with regard to AHM’s rather attenuated argument on Article III standing.

Gorsuch pressed AHM’s attorney Erin Hawley — wife of arch-conservative Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., with a somewhat checkered history of appearances before the Supreme Court — on the correlation between the harm AHM alleged and the remedy it seeks. He commented that typically, in the case of a handful of individuals with conscience-based objections — here, doctors who oppose performing abortions — the appropriate remedy would be to allow equitable relief such that would simply exempt those particular individuals from any legal requirement to perform the objectionable activity, and as Gorsuch himself said, “go no further.”

“[B]ut recently … one might call it a rash of universal injunctions or vacatures and this case seems like a prime example of turning what could be a small lawsuit into a nationwide legislative assembly on an FDA rule or any other federal government action,” continued Gorsuch in a warning.

He went on, appearing to tip his hand to his position on AHM’s request.

“You’re asking us to extend and pursue this new remedial course which this court has never adopted itself,” he said. “Lower courts have kind run away with it.”

The legal community noticed Gorsuch’s hostility toward AHM’s position immediately.

Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern commented on X (formerly Twitter) that Gorsuch’s words from the bench amounted to “undisguised contempt” for Kacsmaryk’s ruling and predicted, “Obviously a bad sign for the anti-abortion advocates here.”

Likewise, The Nation’s Elie Mystal noted that Gorsuch’s comments from the bench indicated that he was “‘in play’ for keeping the abortion pill.”

Jackson, who is usually known for landing on the opposite end of the ideological spectrum from Gorsuch, picked up where her fellow justice left off.

Jackson said it made “perfect sense” for individual doctors to ask for a conscience-based exemption, but questioned why such a request should mean that “everyone else should be prevented from getting this kind of medication.” The justice said she was concerned about the “mismatch between claimed injury and the remedy that’s being sought.”

“Why isn’t that plainly overbroad?” Jackson demanded.

Hawley argued that doctors in emergency situations might be forced, over their conscience objection, to perform abortions. Jackson, however, pointed out that no such doctor has actually pleaded that they fit into Hawley’s hypothetical.

Jackson pressed Hawley, “Can you point to any place in the declaration where respondents attempted to object and couldn’t?”

A stammering Hawley admitted that no such declaration existed, and explained that doctors who scrub into surgeries do not necessarily know what kind of procedure they will be performing.

Jackson was both unconvinced and unrelenting.

“Assuming we have a world in which they can actually lodge the objections that you say that they have, isn’t that enough to remedy their issue?” she asked. “Or do we also have to also entertain your argument that no one else in the world can have this drug — or no one else in America should have this drug — in order to protect your clients?”

Only Thomas and Alito appeared to be receptive to AHM’s standing argument.

Alito zeroed in on Danco’s financial interest in mifepristone, pointing out that the pill is the only drug the company is currently marketing and asking, “I gather your injury is, you think you’re going to sell more if restrictions that were previously in place were lifted. You’re going to make more money?”

When Ellsworth answered that the company’s injury is that it might be prevented from selling a product that has been approved by the FDA, Alito asked, “You think the FDA is infallible?”

Ellsworth returned the colloquy to the primary issue at hand, and argued that AHM’s argument is “revolutionary” in that it is contending that people who neither use nor prescribe a product have the right to seek a court order upending an FDA drug approval.

Jackson later flipped Alito’s question on its head and asked whether it should be left to judges to parse medical and scientific studies and make independent determinations on efficacy and safety.

“Do you think courts have specialized knowledge on pharmaceuticals?” Jackson asked Ellsworth, who answered that courts are not in the position to second guess the FDA’s scientific judgment.

Although Supreme Court has shown itself to be divided on issues involving abortion law, it has often acted with one mind on procedural matters such as standing, even when the underlying lawsuit relates to abortion. Ruling against AHM on the issue of standing would allow the justices to shut down Kacsmaryk’s sweeping order without giving up any ground on the underlying issues of either abortion or administrative agency law.

You can listen to the full oral arguments here.

Brandi Buchman contributed to this piece.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]