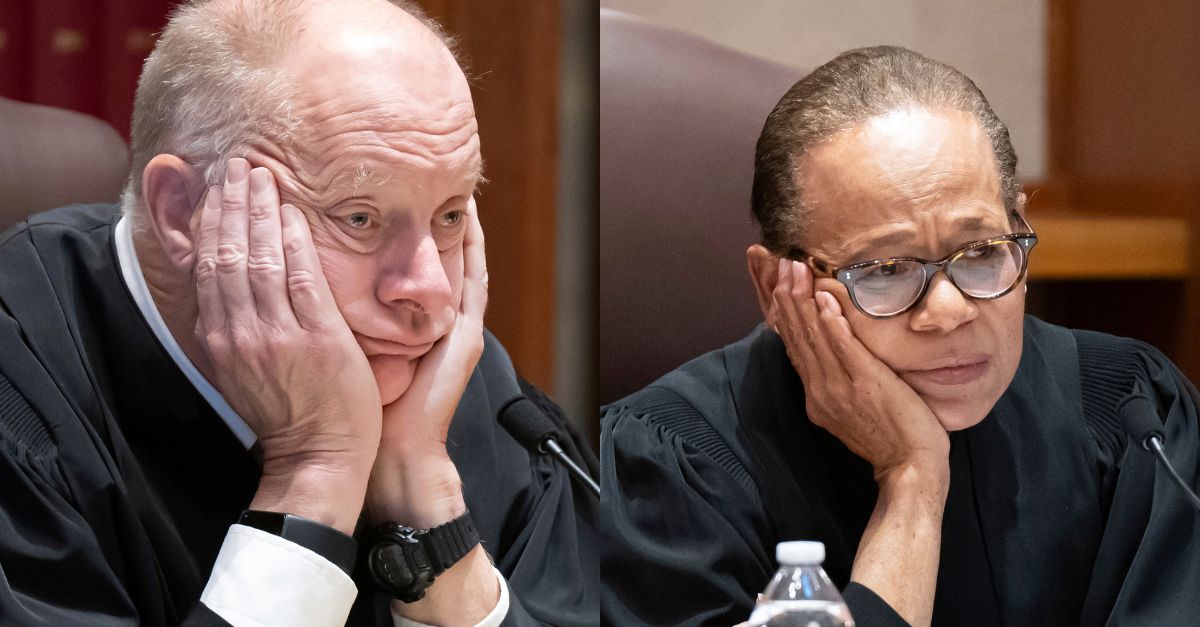

Left: Judge Sarah B. Wallace speaks during a hearing for a lawsuit to keep former President Donald Trump off the state ballot in Denver District Court Thursday, Nov. 2, 2023, in Denver. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski, Pool). Right: Donald Trump closes his eyes against the sunlight as patriotic music plays before he gives remarks during a campaign event held at Trendsetter Engineering Thursday, Nov. 2, 2023, in Houston. (AP Photo/Michael Wyke)

The question of whether Donald Trump can remain on the ballot in Colorado for the 2024 election has continued to unfold rapidly and is nearing its conclusion as other challenges in different states are only starting to gather momentum.

The trial in Colorado launched on Monday before Second Judicial District Judge Sarah Wallace has already seen a slog of witnesses from either side appear. There have been constitutional scholars, experts on extremism, congressional lawmakers and activists alike who supported Trump’s 2020 campaign, as well as former Trump administration appointees who have testified. Police who defended the Capitol have also testified.

For the group of voters — including six Republicans and one unaffiliated voter —asking Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold to remove Trump from the ballot, they contend their case is a simple one: Trump’s conduct around Jan. 6 amounts to insurrectionist behavior in violation of Section III of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Civil War-era provision bars any person who has sworn an Oath to the U.S. Constitution and then engaged in insurrection from ever again serving in public office short of amnesty granted by Congress.

The disqualification also stretches to those who provided “aid and comfort” to insurrectionists.

Attorneys representing Donald Trump in Colorado have tried to test the definition of the word “insurrection” plus what it means to “engage” in one. They have also raised whether it is even appropriate for the courts to decide if a state secretary can remove a viable candidate from the ballot.

Trump’s lawyers over the last few days have also elicited testimony arguing that the former president was not, legally speaking, an “officer” of the United States during his presidency and that Section III was only meant to apply to lower offices. Attorneys representing the voters have urged Judge Wallace to consider the evidence and language of the statute plainly. On Wednesday, expert testimony from Indiana University professor Gerard Magliocca went to these points almost entirely.

Magliocca cited various legal examples where insurrections were defined as any use of force or threat of force to hinder or prevent the execution of U.S. laws. He acknowledged though that there was nothing in more recent history that litigated the exact term in its application under Section III. During cross-examination, according to Colorado Newsline, Magliocca also rebuffed the theory that presidents are not “officers” of the United States.

The Equal Protection Clause refers to the president as an “executive officer” and an “official” of the United States, he noted.

Tim Heaphy, the lead investigator for the Jan. 6 committee, also testified on behalf of the petitioners Friday. Heaphy told the court that claims the select committee manipulated footage or transcripts were false. He also rejected the assertion investigators were biased because members of the committee made comments after Jan. 6 claiming Trump was responsible. The committee’s report focused almost entirely on the weeks and months leading up to Jan. 6, he noted.

On Friday, expert witness and University of St. Thomas professor Robert Delahunty testified for Trump and said that while he agreed with Magliocca on some points as well as some interpretations from Stansbury, he was apprehensive. Some of the points Magliocca made, he said, were formed before Section III was ratified.

And the term insurrection in the statute’s final form was too vague, he said.

“It’s not just plain vanilla insurrection, it’s an insurrection against the Constitution of the United States [being considered by Section III],” Delahunty said Friday. “In other words, insurrection is not a free standing term in Section III. It is coupled with… that other phrase, insurrection ‘against the Constitution.””

Whether Trump was acting against the Constitution outright was not clear to him, he explained.

Other witnesses in favor of keeping Trump on the ballot that have testified this week have included Amy Kremer, chair of Women for America First and activist organizer for the “Stop the Steal” movement; former Trump spokesperson Katrina Pierson, former Defense Department aide Kashyap “Kash” Patel; Thomas van Flein, the general counsel to Republican Rep. Paul Gosar of Arizona; and Rep. Ken Buck of Colorado, another Republican lawmaker. The Colorado state GOP’s treasurer, Tom Bjorkland, also testified though not in his official capacity since the Colorado Republican Party filed as an intervenor in the petition to remove Trump from the ballot.

According to CBS, Rep. Buck told Judge Wallace on Wednesday he believed that the petitioners’ reliance on the official congressional committee report investigating Jan. 6 to disqualify Trump was inappropriate since the report was politically motivated.

Buck, who only this week announced that he is not seeking reelection, told the court the select committee failed to cross-examine witnesses or subpoena documents. Attorneys representing the voters rejected the suggestion, noting the committee issued over 1,000 subpoenas. Though Buck appeared to scoff during his testimony Wednesday at Republicans in Congress still making the claim that the 2020 election was stolen, Buck himself was aligned with Trump that year. He added his name to an amicus brief filed in the Texas v. Pennsylvania lawsuit brought to challenge Biden’s victory in the state.

Kremer also testified that she did not believe Trump told people to violently storm the Capitol during his speech on Jan. 6.

Those who came to Washington were “happy warriors,” who were “full of love,” she said. She also testified that she personally did not witness anything indicating imminent violence during Trump’s speech at the Ellipse.

The New York Times noted that in her testimony under cross-examination, she admitted that her view of things was limited that day, however: She was safely behind security gates where she wouldn’t be able to see how things were really unfolding on the ground.

Rep. Paul Gosar’s former general counsel Thomas Van Flein, another prominent voice supporting Trump’s claims of a “stolen” election in the run-up to Jan. 6, testified that Jan. 6 was peaceful and “more like a festival than a rally” and that “there was no anger.”

Van Flein also said that he did not stay for the entirety of Trump’s speech.

While Van Flein may not have witnessed anger personally; many of those at the Capitol to support the former president on Jan. 6 were armed and police who defended the building have testified at length this week — and historically — about their treatment by a crowd that overwhelmingly resisted their orders to stand down and leave.

Like Van Flein, Colorado Republican treasurer Tom Bjorklund testified that he did not witness violence from any Trump supporters while he attended the “Stop the Steal” rally on Jan. 6.

Bjorklund, who brought body armor to Washington, D.C., but did not wear it on Jan. 6, said he was worried about being attacked by “antifa” while he was there. Bjorklund also said he did not go inside the Capitol himself though he watched others incite people to enter, namely, leftists or members of antifa.

There has never been any evidence to support the claim that “antifa” incited violence on Jan. 6 and the intelligence community has dismissed the notion. Nonetheless, it has been a popular conspiracy theory for more than a year.

When Kash Patel testified, he denied any suggestion by the petitioners that Trump failed to call the National Guard or that the former president stalled any efforts to help lawmakers and police he understood to be badly outnumbered. Patel instead blamed Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser, claiming she had denied aid.

Patel said that Trump had ordered at least 10,000 to 20,000 troops from the National Guard to reinforce U.S. Capitol Police and the D.C. Metropolitan Police officers. This conflicts with testimony Defense Department Secretary Chris Miller gave to the Jan. 6 committee last year. When Miller testified under oath he said Trump “never” gave a direct order to have the National Guard called up. He has waffled on this question historically: a month before his sworn, Miller said on Fox News that Trump had ordered the troops.

‘Should we do it?’

Meanwhile on Thursday, at the Minnesota State Supreme Court, justices there began hearing arguments for the first time about Trump’s qualifications under Section III. Voters are represented there by the group Free Speech for the People.

According to Politico, one member of the court there, Chief Justice Natalie Hudson, questioned whether the matter was something the state’s high court could resolve at all.

“Should we do it? Even if we could do it and we can do it?” she said.

Hudson said she expected the U.S. Supreme Court would eventually need to resolve the matter.

Paul Thissen, a fellow justice on the Minnesota Supreme Court, struggled with the question of whether Section III included presidents. Constitutional scholars have asserted that it must since excluding presidents would otherwise turn the nation’s guiding legal document into a “historical ornament.”

Minnesota Supreme Court Associate Justice Paul Thissen listens as the attorney for former President Donald Trump, Nicholas Nelson argues before the Minnesota Supreme Court Thursday, Nov. 2, 2023, in St. Paul, Minn., as the court hears arguments on the case to keep Trump off the ballot. (Glen Stubbe/Star Tribune via AP, Pool)/Minnesota Supreme Court Chief Justice Natalie Hudson questions Ronald Fein, attorney for the petitioner, “Free Speech for People,” as he argues his case before the court Thursday, Nov. 2, 2023, in St. Paul, Minn. The Minnesota Supreme Court heard arguments to keep former President Donald Trump off the ballot. (Glen Stubbe/Star Tribune via AP, Pool)

It is unclear when the court in Minnesota will rule, but in Colorado, Judge Wallace is expected to render a decision by Thanksgiving.

Just a day after his trial opened in Colorado, Trump sued to stop Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson from declining to include Trump on the ballot in the primary there in 2024 or in the general election.

The lawsuit asks Benson to decide whether he is disqualified or not under Section III and asks for an injunction to include him. Benson has already said she would not keep Trump off the ballots unless the courts explicitly direct her to.

As of Oct. 31, there were currently 16 cases pending throughout the U.S. asking the courts to step in and disqualify Trump. Five additional cases were voluntarily dismissed already by late October and only one challenge brought in Florida has been outright dismissed by the court, according to a tracker from Lawfare.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]