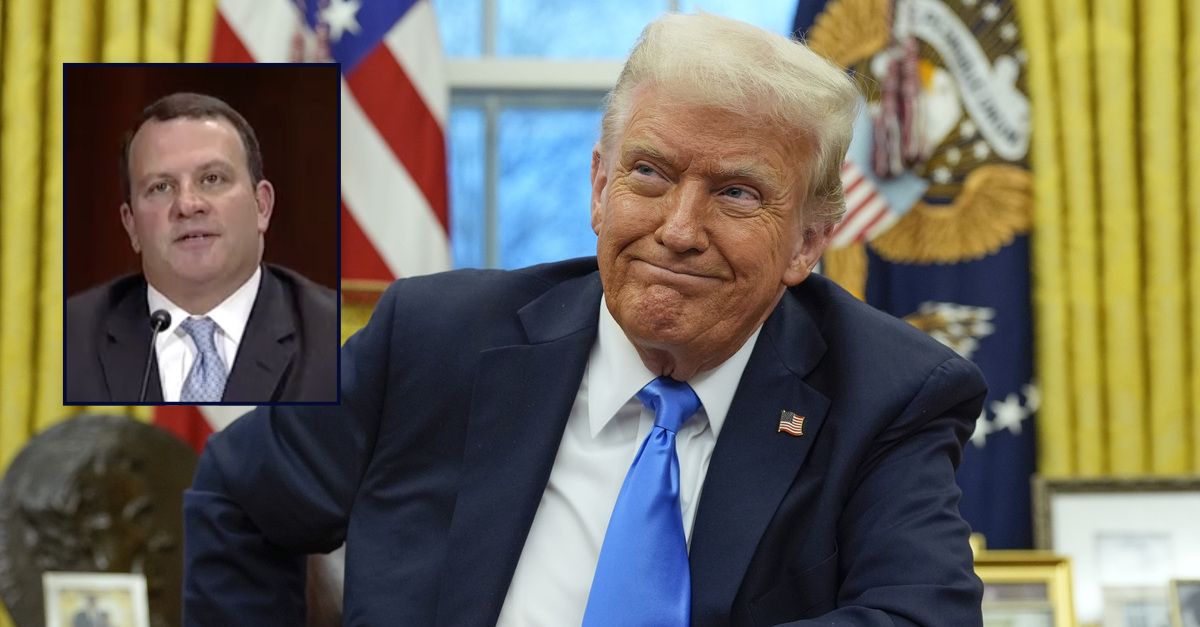

Inset: U.S. District Judge Timothy J. Kelly (Senate Judiciary Committee). Background: President Donald Trump speaks with reporters in the Oval Office at the White House, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2025, in Washington, D.C. (Photo/Alex Brandon).

A federal judge on Thursday barred the Trump administration from deporting hundreds of Guatemalan children living in the country without their parents in a decisive ruling against immigration officials.

In a 43-page memorandum opinion, U.S. District Judge Timothy J. Kelly, appointed by President Donald Trump during his first term, unequivocally rejected the arguments leveled by government lawyers as not only unpersuasive but also likely premised on lies.

The court”s ruling begins with an uncharitable description of the since-frustrated plan to quickly deport the children in question.

“Just before midnight on the Saturday of Labor Day weekend, several Executive Branch agencies began to implement a plan to expel from the United States certain unaccompanied alien children in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services and send them back to their home country of Guatemala,” Kelly writes. “Those agencies told the children’s caretakers, who were hearing about the plan for the first time, to have them ready for pickup in as little as two hours.”

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

Working quickly, attorneys representing the children filed their lawsuit by 1 a.m. the next morning, aiming to represent a class of “hundreds of Guatemalan children at imminent risk of unlawful removal” and premised on several statutory and constitutional violations.

In turn, lawyers with the U.S. Department of Justice telegraphed outrage at the attempt to keep the children in the country. The judge described this plaintiff-blaming in withering terms.

“At a hearing later that day, counsel for Defendants explained why it was ‘fairly outrageous’ for Plaintiffs to have sued: all Defendants wanted to do was reunify children with parents who had requested their return,” Kelly’s opinion goes on. “But that explanation crumbled like a house of cards about a week later.”

In fact, the government’s own follow-up filings undercut their initial in-court statements, as Law&Crime previously reported.

On Sept. 8, an exhibit filed by the Trump administration cited Guatemalan law enforcement’s own efforts with regard to the children – noting a series of home visits which showed only 50 parents “were willing to welcome back their children if they were to return, with the caveat that none of them was requesting their return.” Then, during an ensuing hearing, a DOJ lawyer admitted her colleague had previously made statements not supported by the evidence.

Kelly puts a fine point on the evidentiary breakdown.

“There is no evidence before the Court that the parents of these children sought their return,” the opinion continues. “To the contrary, the Guatemalan Attorney General reports that officials could not even track down parents for most of the children whom Defendants found eligible for their ‘reunification’ plan. And none of those that were located had asked for their children to come back to Guatemala.”

A temporary restraining order was issued by U.S. District Judge Sparkle Sooknanan, a Joe Biden appointee, during the early morning hours – and within hours – after the lawsuit was filed. On Wednesday, Kelly briefly extended the restraining order until 11:59 p.m. on Sept. 18 – only explaining that the extension was based on “good cause.”

Now, the judge has seemingly offered an explanation.

From the opinion, at length:

Before “conducting home visits” with those families, the office called them and “discovered that the families were surprised”—and “some even annoyed”—by the outreach because “many” did “not expect” their children “to be returned to Guatemala.” Some “calls went unanswered” or to “disconnected” phone lines. And when the office tried to visit the homes, parents for 59 of the children “reject[ed] the request” and refused to “subject themselves to an assessment to determine if they were a suitable family resource.” In the end, only parents for about 50 to 57 of the 609 children that ORR identified to Guatemala “were willing to welcome back their children.” Even within that small group, though, “none of them was requesting their [child’s] return.” The parents of one child explained why: their daughter “had received death threats and therefore could not live in” Guatemala, so they would “do everything possible to get her out of the country again” if the United States sent her back.

While granting an injunction barring the planned deportations, the court also certified a class made up of all Guatemalan children “in (and who will be in)” the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement “who have not received a final order of removal” or permission to “voluntarily depart” under applicable laws and regulations.

Again, the court rejected government arguments that the class should be limited only to the named plaintiffs in the lawsuit.

And, again, the government’s misrepresentations about the desires of the children’s parents are cited to support the ruling.

“[T]he record here is barren of evidence that any child in the proposed class wants to return to Guatemala, even if their parents can be found,” Kelly writes. “All the evidence suggests the opposite: Plaintiffs have offered over 30 declarations from Guatemalan children who object to being sent back. And Defendants offer no specific example supporting their claim that ‘[m]any Guatemalan children may benefit’ from ‘reunification.'”