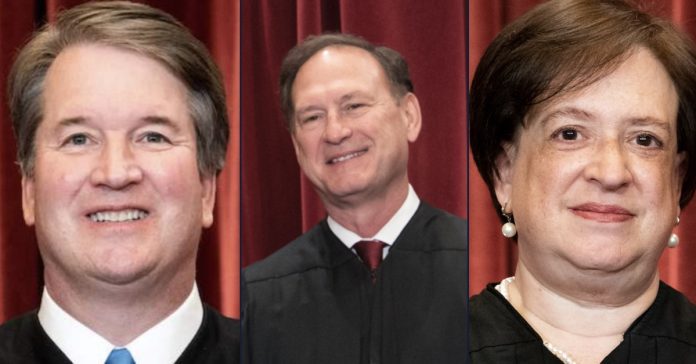

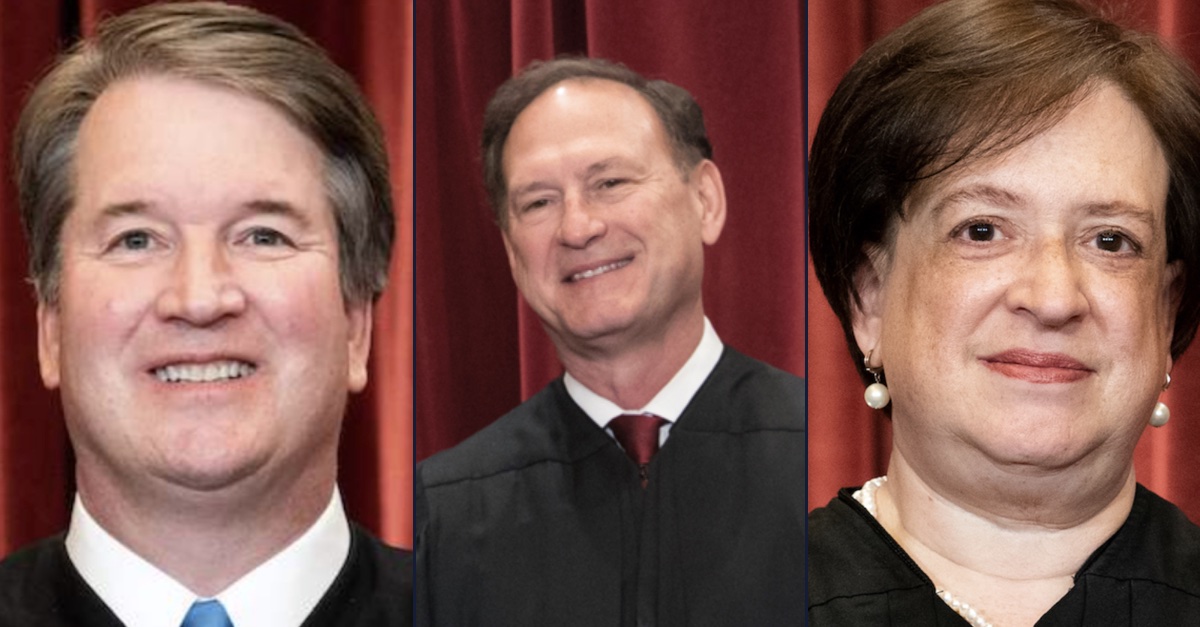

Justice Brett Kavanaugh (ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images), Justice Samuel Alito (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite), Justice Elena Kagan (ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

The Supreme Court heard arguments on Monday in Murthy v. Missouri, the case out of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit asking the justices to decide whether the Biden administration ran afoul of the First Amendment by urging social media platforms to take down content. Along the way, Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Elena Kagan, one formerly a prominent Bush administration staff secretary and the other formerly the Solicitor General of the United States during the Obama administration, took a dim view of a nightmare scenario raised by Justice Samuel Alito that the case could open the door to the New York Times and other major newspapers being inundated by government demands to censor stories.

Principal Deputy Solicitor General of the United States Brian Fletcher framed the government petitioner’s communications with social media companies as little more than “bully pulpit exhortations” and encouragement to exercise their lawful right to moderate and remove misinformation from their platforms, but particularly during the emergency circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The justices agreed to decide whether the respondents — the states of Missouri and Louisiana, Dr. Aaron Kheriaty, Dr. Martin Kulldorff, Dr. Jayanta Bhattacharya, Jill Hines, and The Gateway Pundit’s Jim Hoft — had standing to sue, whether the government’s encouragement of social media companies to remove content deemed misinformation or disinformation amounted to impermissible coercion, and whether the Fifth Circuit’s injunction was too broad or proper.

Recall that a conservative three-judge panel on the Fifth Circuit ruled in Missouri v. Biden that officials in the FBI, CDC, the White House, and the COVID-19 Response Team likely violated the First Amendment by “coercing and significantly encouraging ‘social-media platforms to censor disfavored [speech].”” Days later, the Biden administration asked the Supreme Court to put the resulting injunction on hold. Myriad briefs hit the docket thereafter, in which the respondents claimed that their posts about COVID-19 vaccine mandates and the lab-leak theory, Hunter Biden’s laptop, election fraud claims, and more were “censored” because social media companies were overwhelmed by the government’s demands.

Fletcher leaned on the Supreme Court case Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan and advanced the government argument that the Fifth Circuit “radically expanded the state action doctrine” by finding that FBI communications with social media platforms were inherently coercive since it is a law enforcement agency.

The government lawyer then wondered how efforts to encourage the removal of antisemitic or Islamophobic content, content that implicates national security issues, and content harmful to children’s mental health might be impacted if the court were to accept the respondents’ arguments.

A “vague injunction” like this hanging over the heads of government officials “is a real problem,” Fletcher said. He further argued that the respondents “haven’t shown any causal connection” between their alleged post removals and the government’s communications.

That’s when Justice Alito advised that SCOTUS doesn’t “usually reverse findings of fact that had been endorsed by two lower courts.”

Fletcher focused in on a dearth of traceability and pointed to social media platforms’ policies, noting the “platforms were moderating this content long before the government was talking to them.”

“They had powerful business incentives to do the same thing,” consistent with their own policies,” he said.

Alito shot back that the record before the court shows government officials “demanding answers,” cursing people out, carrying on “constant pestering” of Facebook, sending constant emails, setting constant meetings, declaring, “we want answers, we’re on the same team.” Imagine, Alito continued, what the narrative would be if the government was doing this to news organizations — seemingly suggesting that the New York Times and media more broadly could be next.

“If you did that to them, what do you think the reaction would be?” Alito asked, commenting that the government has Section 230 and antitrust “in its pocket.”

“Would you do that the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal, or the Associated Press, or any other big newspaper of wire service?” Alito asked Fletcher. “And I just can’t imagine the federal government doing that to them, but maybe I’m naive. Maybe that goes on behind the scenes.”

When Fletcher acknowledged that there was an “intensity” and an “anger” in some of the cited communications that he found to be “unusual,” he just as quickly said the pandemic was unusual.

Fletcher later argued that the fact “very large, very powerful corporations” that are “very sophisticated” were involved here — and were often pushing back or outright refusing government requests — only supports the Biden administration’s contention that there was no coercion (i.e., “adverse government action”).

Justice Kavanaugh, for his part, quickly responded to Alito’s line of questioning and also Fletcher’s use of the term “unusual.”

“You said the anger here was unusual,” Kavanaugh said. “I wasn’t entirely clear on that from my own experience.”

Alito then chimed in sardonically to say maybe that high court should tell the Public Information Office that they can email the press when the justices don’t like certain news stories and curse people out to pressure them to change or otherwise remove content critical of the nine.

This would not be the last time that Kavanaugh harped on this point, and Justice Kagan joined in later too. Kavanaugh again, from real-world experience, framed communications from government to media as commonplace.

When Louisiana Solicitor General Benjamin Aguinaga began his oral argument, he stated that “government censorship has no place in our democracy” and that the “stunning” and “unrelenting pressure” he asserts happened in this case is “arguably the most massive attack against Free Speech in American history.”

The government is “not using the bully pulpit at all,” Aguinaga said, it’s “just being a bully” by “deliberately” setting out to “suppress speech,” just as was the case in Bantam Books.

Kagan, describing Aguinaga’s argument as “extremely expansive,” also found Alito’s warning odd.

“Like Justice Kavanaugh, I’ve had some experience encouraging press to suppress their own speech,” Kagan said, whether about a bad editorial or a story riddled with factual errors. “This happens literally thousands a time a day in the federal government.”

Picking up on the theme, Chief Justice John Roberts attempted to inject some levity in an otherwise contentious oral argument.

“I was just going to say first I have no experience coercing anybody,” Chief Justice John Roberts joked, eliciting laughter in the court.

For Aguinaga, though, this case is not only about COVID, but also about election integrity.

“Whatever it is, if the government is attempting to abridge the speech rights of a third party, that has to be unconstitutional because that falls within the plain text of the First Amendment,” Aguinaga added.

“The problem here,” he continued, is that the “platforms themselves reversed course on their own policies” in response to government demands.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson posed a hypothetical to probe Aguinaga’s reasoning. She wanted to know whether it would be a First Amendment violation for the government to respond to a defenestration epidemic amongst American youths participating in a harmful internet “challenge” by encouraging social media sites to remove such content.

“In that circumstance, can the government call the platforms and say this information that you are putting up on your platform is creating a serious public health emergency, we are encouraging you to take it down?” Jackson asked.

“I was with you right until the last comment, your honor,” Aguinaga answered.

Chief Justice Roberts followed up: “Does that rise to the level of coercion that you think is problematic?”; “That violates the Constitution?”

It’s a First Amendment problem when the government identifies “an entire category of content that it wishes to not be in the modern public sphere,” Aguinaga replied, pointing to 20,000 pages in the record of persistent government pestering of platforms.

“The bulk of it is behind closed doors, that’s what so pernicious about this case,” he added.

Kagan eventually cut right to the chase, asking Aguinaga for the “single piece of evidence that most clearly shows” the government was responsible for having material taken down. The attorney pointed to respondent Jill Hines’ posts referencing RFK Jr., Tucker Carlson, and vaccines.

The justice responded: How do you know it’s government action as opposed to platform action based on one email that was sent two months before the alleged adverse action occurred?

Kagan, adding that it appears hard to “overbear Facebook’s will,” seemingly made the case that many individuals who argue Silicon Valley is too powerful are simultaneously claiming those companies were powerless once the government sent a stern email — or even angry email — on an issue of concern.

“I don’t see a single item in your briefs that would satisfy our normal tests,” Kagan said flatly.

Kavanaugh, drawing a distinction between the government requesting the removal of factually erroneous information and targeting viewpoints, also emphasized that there’s evidence of the platforms repeatedly saying “no” to content removal requests.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]