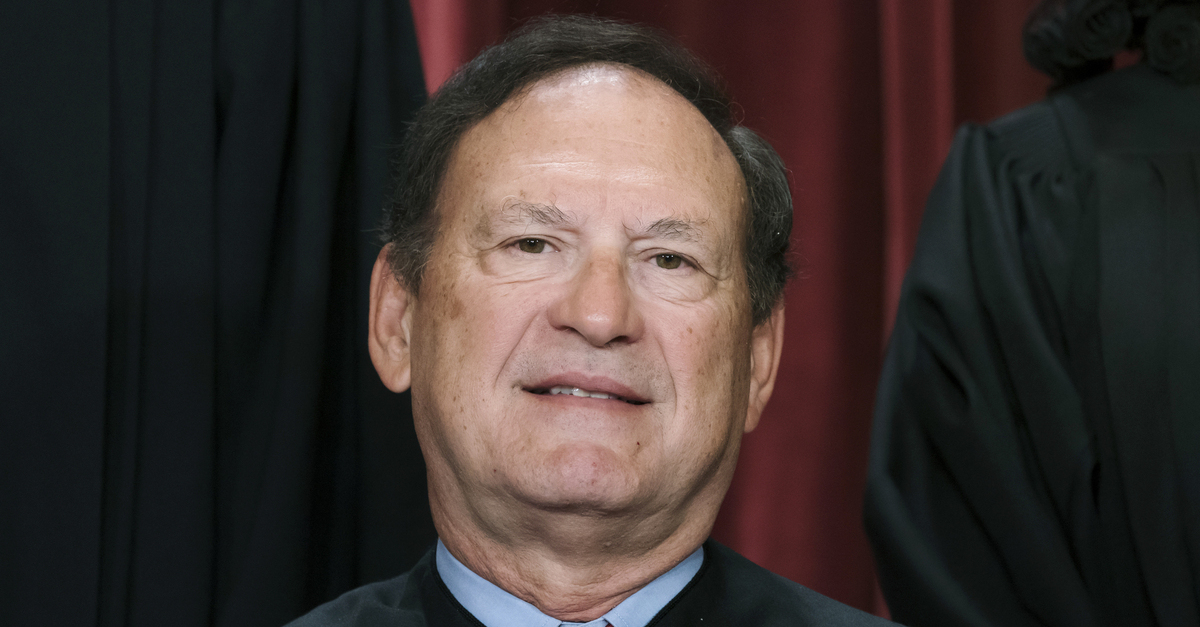

FILE – Associate Justice Samuel Alito joins other members of the Supreme Court as they pose for a new group portrait, Oct. 7, 2022, at the Supreme Court building in Washington. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito complained about the impact of legalizing same-sex marriage on “society” in a statement about a case that does not have anything to do with same-sex marriage on Tuesday.

The underlying case was an employment discrimination lawsuit filed by a lesbian prison guard — which she won. On Tuesday, in orders, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal filed by the Missouri Department of Corrections over part of the jury selection process.

The outspoken conservative justice begrudgingly agreed with the court denying the petition for writ of certiorari — citing technical grounds that complicated the case — but took the opportunity to offer his views on how LGBTQ rights intersect with religious beliefs.

“In this case, the court below reasoned that a person who still holds traditional religious views on questions of sexual morality is presumptively unfit to serve on a jury in a case involving a party who is a lesbian,” Alito wrote — offering a generalized summary of the case.

The upshot of the case, Alito argues, is that he now sees himself as having correctly predicted anti-religious fallout from the landmark Supreme Court ruling legalizing same-sex marriage.

“That holding exemplifies the danger that I anticipated in Obergefell v. Hodges, namely, that Americans who do not hide their adherence to traditional religious beliefs about homosexual conduct will be ‘labeled as bigots and treated as such’ by the government,” his Tuesday statement reads. “The opinion of the Court in that case made it clear that the decision should not be used in that way, but I am afraid that this admonition is not being heeded by our society.”

Jean Finney won at both the district and appellate court levels in Missouri — proving her employers created “a hostile work environment” and discriminated against her “on the basis of sex.”

One of the central issues in the case was that Finney is a lesbian. So, her counsel asked potential jurors some questions about whether their religious upbringing denigrated homosexuality as a “sin.”

Alito complains the questions posed by Finney’s attorney “conflated two separate issues: whether the prospective jurors believed that homosexual conduct is sinful and whether they believed that gays and lesbians should not enjoy the legal rights possessed by others.”

Still, the questions were allowed and asked.

“The trial court, sua sponte, raised striking for cause certain jurors who had answered that homosexuality was a sin or otherwise expressed bias against homosexuals,” Finney’s reply brief explains.

Following the judge’s lead, Finney’s counsel moved to strike three jurors. Explaining its decision as erring “on the side of caution,” the judge struck the jurors but went on to muse in dicta that none of the Christians had actually said anything indicating they would have been legally biased against Finney — and in fact had said the opposite. In any event, the court noted, there were more than enough jurors anyway.

After Finney won, the department of corrections moved for a new trial — which was denied. On appeal, the government claimed the three jurors “were improperly struck based on their religion.”

The state’s procedural posture, however, overstated the reason why the jurors were dismissed by the trial court in Buchanan County.

The Missouri Court of Appeals found the strikes were not “based on” the jurors’ “status as Christians” but “instead were based on specific views held by the prospective jurors directly related to the case.”

Alito argues that a distinction between religious status and religious beliefs should trigger the same level of scrutiny when reviewed by a court. His statement suggests the level of scrutiny a reviewing court should apply in such cases would almost never allow for such “differential treatment.”

The justice, a salve to the conservative movement when he was nominated to replace Texas attorney Harriet Miers, said the issues in the case are important for the Supreme Court to consider later on.

“When a court, a quintessential state actor, finds that a person is ineligible to serve on a jury because of his or her religious beliefs, that decision implicates fundamental rights,” Alito writes in his five-page statement. “Jurors are duty-bound to decide cases based on the law and the evidence, and a juror who cannot carry out that duty may properly be excused. But otherwise, I see no basis for dismissing a juror for cause based on religious beliefs.”

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]