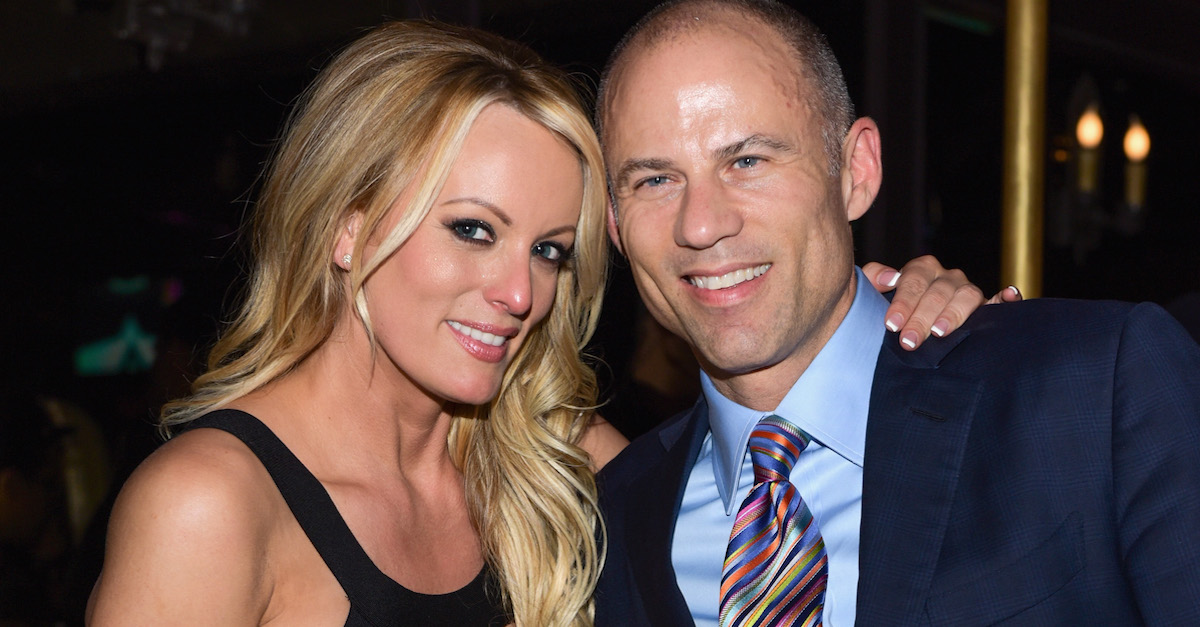

WEST HOLLYWOOD, CA – MAY 23: Stormy Daniels and attorney Michael Avenatti are seen at The Abbey on May 23, 2018 in West Hollywood, California. (Photo by Tara Ziemba/Getty Images)

Fallen attorney and inmate Michael Avenatti lost out on his appeal of his convictions in a fraud and aggravated identity theft case connected to his swindling of his then client, porn star Stormy Daniels, of book advance money she earned from her memoir “Full Disclosure.”

After Avenatti initially parlayed his fame as Daniels’ celebrity lawyer into a sustained media and social media blitz complete with aspirations of challenging then President Donald Trump in the 2020 election, his ascent dramatically shifted to complete collapse and suspension from the, upon convictions for disgracing the legal profession to extort Nike, to defraud Daniels, and to rip off other clients.

On Wednesday, a panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit counted the ways Avenatti’s appeal of his convictions in the Daniels case failed to persuade. U.S. Circuit Judges Eunice Lee and Sarah Merriam, Joe Biden appointees, and Steven Menashi, a Donald Trump appointee, were in agreement that “any error in the jury instructions” in the Daniels case “was harmless,” as the evidence was “overwhelming” that Avenatti stole $297,500 in book advance money from Daniels by having an employee “forge his client’s signature for the purpose of wrongfully obtaining her money.”

“Specifically, AVENATTI stole two installments of Daniels’ book advance, totaling $297,500. AVENATTI sent to Daniels’ literary agent a fraudulent and unauthorized letter purporting to be from Daniels and appearing to bear her signature, which directed that future payments be sent to a bank account controlled by AVENATTI,” the court noted. “In fact, AVENATTI wrote the letter himself, never received authorization from Daniels, and caused Daniels’ signature to be copied and pasted from another document onto the letter without her consent.”

Avenatti went on to use $148,750 of the book advance money to “satisfy his own personal and business expenses” and then “lied” to Stormy Daniels about where the money was, the summary order continued. When Daniels threatened to take action, Avenatti found another way to hide the truth.

“When Daniels began inquiring of AVENATTI as to why she had not received the payment, AVENATTI lied to Daniels, telling her that her publisher had not made the payment,” the order said. “Approximately one month after diverting the payment, after Daniels threatened to go directly to her publisher about the missing payment, AVENATTI obtained a personal loan to pay $148,750 to Daniels, so that Daniels would not realize that AVENATTI had previously taken and used Daniels’ money.”

Despite the foregoing, Avenatti maintained that the federal trial court “erred” when instructing the New York-based federal jury on how the professional obligations of lawyers could factor into their evaluation of whether he “engaged in a scheme to defraud and whether he did so with knowledge and an intent to defraud”; pressured deadlocked jurors to reach a verdict by repeatedly issuing Allen charges; and unlawfully ordered him to pay $148,750 in restitution to Daniels before he paid restitution to Nike. Avenatti further claimed that the U.S. Supreme Court case Dubin v. United States should undo his aggravated identity theft conviction.

All of these arguments were losing ones, but the circuit judges dispensed of the doomed and “meritless” restitution complaint by pointing out that Avenatti’s lawyer already waived an objection to paying Daniels before Nike [citations removed for ease of reading]:

On September 22, 2022, the government proposed a restitution order that would require Avenatti to provide restitution to his client before he paid Nike. Prior to proposing that order, the government conferred with Avenatti’s counsel, who raised no objection. The district court issued the restitution order on September 23, 2022.

On appeal, Avenatti argues that we should vacate the restitution order because it directs restitution payments to be paid in this case before the previous one. Because the government consulted with Avenatti prior to proposing the restitution order, and because Avenatti’s counsel “made a considered decision not to object,” Avenatti has waived this objection. Even if he had not, the objection would be meritless. Though “a district court may not alter an imposed sentence,” a “modification of the terms of payment of restitution is not a modification in sentence.” To the contrary, “as long as [the] amount of restitution remains [the] same, alteration in terms of repayment does not alter [the] sentence.” For that reason, the change in the schedule of payments was not an impermissible alteration of the sentence.

Federal prison records reviewed by Law&Crime show that Avenatti, now 53, has a release date of Sept. 4, 2035.

Read the summary order from the Second Circuit here.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]