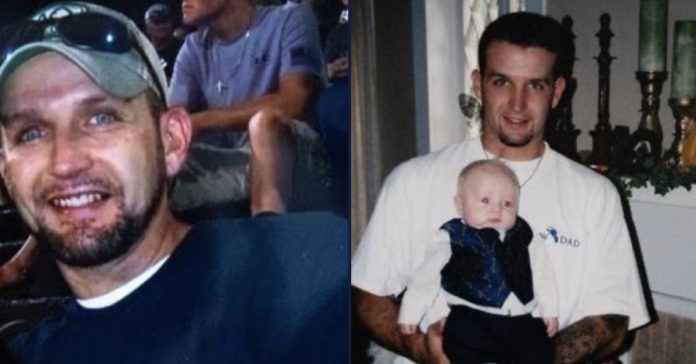

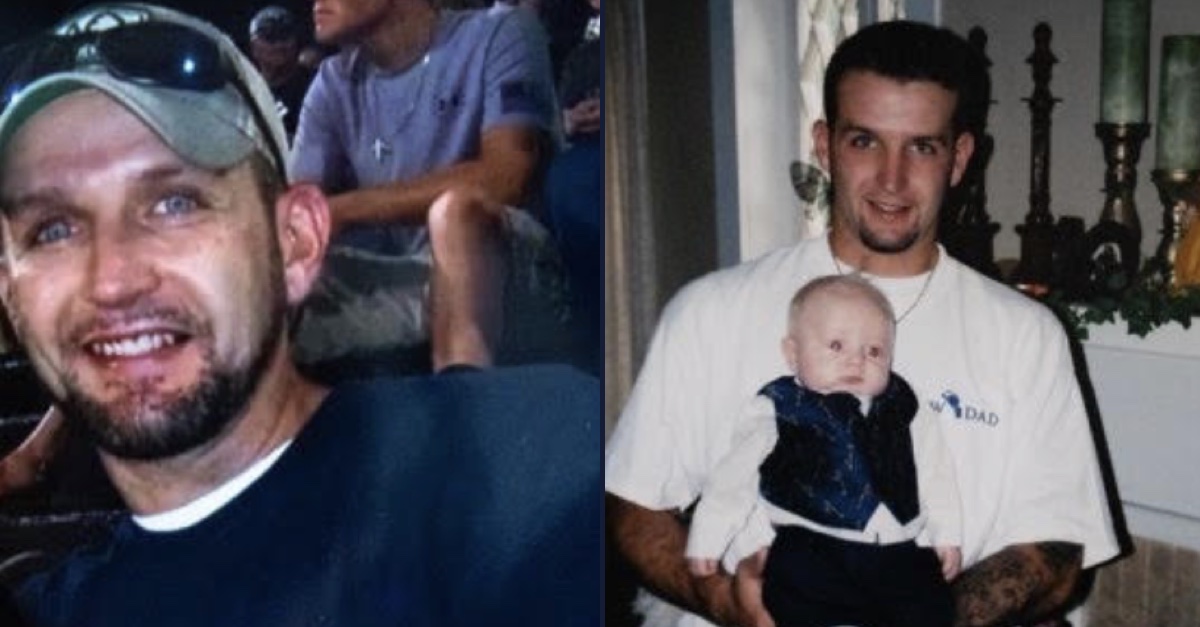

Ventress Correctional Facility, as shown in a local news report from 2019 (WDHN/screengrab), Brandon Dotson (right) in a photo from the lawsuit.

A 43-year-old Alabama inmate serving a 99-year burglary sentence died in prison the “same day he was considered for parole release” and now his family, which “had no choice but to hold a closed casket funeral service,” has no idea where his heart is, a federal lawsuit against the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) alleged.

Brandon Clay Dotson wasn’t sentenced to die at the Ventress Correctional Facility in Clayton, but the sentence was “tantamount to a death sentence,” said the lawsuit filed by Dotson’s daughter Audrey Marie Dotson and his mother Audrey South.

The Thursday complaint named ADOC Commissioner John Q. Hamm, ADOC Chief Deputy Commissioner of Corrections Greg Lovelace, Ventress Correctional Facility Warden Karen Williams, Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences Director Angelo Della Manna, multiple unnamed prison employees, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine (UABSOM) as defendants.

The plaintiffs alleged that after Warden Williams notified them of Brandon Dotson’s death, Dotson’s mother, daughter, and brother “spent days attempting to claim his body, in hopes of holding his funeral before Thanksgiving Day.”

Instead, Dotson’s body was so “severely decomposed” five days after his death — when the family received his remains — that an open casket funeral was not an option.

“For days the family attempted to claim his body after submitting the proper paperwork as soon as they were alerted to his untimely death. Finally, his body was released to his family nearly a week later on November 21, 2023. At this point the body had not been properly stored and was severely decomposed,” the lawsuit said. “Despite the family’s initial wishes, they had no choice but to hold a closed casket funeral service.”

Even more alarming, Dr. Boris Datnow, a pathologist the family “retained” to perform a second autopsy, discovered that “the heart was missing from the chest cavity of Mr Dotson’s body,” the lawsuit continued.

“The Alabama Department of Corrections – or an agent responsible for conducting the autopsy or transporting the body to his family – had, inexplicably and without the required permission from Mr. Dotson’s next of kin, removed and retained Mr. Dotson’s heart,” the complaint said.

The lawsuit explained that UABSOM was being sued as a “possible intended recipient of Mr. Dotson’s heart,” citing a recent history of facilitating medical student “laboratory exercises involving human organs and tissues” from deceased inmates.

But the lawsuit was clear that, “[t]o date, no one has explained to the family why Mr. Dotson’s heart was missing when his body was turned over to them” and plaintiffs “do not know where Mr Dotson’s heart currently is, or in whose possession.”

Dotson’s mother and daughter filed the suit to “seek the immediate return of Mr. Dotson’s heart” so the vital organ “may be examined by an autopsy pathologist and then properly cremated or interred.”

Brandon Dotson (in family photos provided by attorney)

The plaintiffs also brought claims of Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment violations, deliberate indifference to Dotson’s serious medical needs, health, and safety, conspiracy to cover up the allegedly deliberate indifference, wrongful death, interference with the right of burial, intentional and negligent mishandling of a corpse, unjust enrichment, spoliation of evidence, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and failure to notify the next of kin when retaining organs.

For instance, the lawsuit alleged Dotson had asked for help in the days before he died, saying that another inmate was targeting him for violence.

Prison officers allegedly responded to that call for help by removing Dotson from “segregated housing” and “return[ing] him to general population, where he could access drugs and be attacked easily by those seeking to harm and exploit him” in the “grossly understaffed and severely overcrowded” part of the prison.

“No member in the correctional staff was available to prevent the abuse Mr. Dotson endured and the constant and unlimited access to drugs that he had, or to rescue Mr. Dotson timely to save his life, or if they were available, they ignored the warning signs and direct pleas for help when they had every opportunity to intervene and prevent the death of Mr. Dotson,” the suit claimed.

Then, on the day the Dotson was found dead in his bed, his “body had already begun to stiffen” — and Dotson’s family still doesn’t know how he died or exactly when, according to the complaint.

“Defendants performed an autopsy on the deceased and removed the heart, thereby concealing the true cause of death. By taking this action, Defendants intentionally or recklessly destroyed or altered key evidence that deprived Plaintiff of the ability to determine how the deceased died through an independent autopsy,” the lawsuit said. “The heart is a vital organ that would provide critical evidence in assessing the cause of death. Without the heart, Plaintiff cannot obtain an accurate and complete determination of the circumstances surrounding the deceased’s death.”

The family said that when they saw Dotson’s body they observed “bruising on the back of [his] neck and excessive swelling across his head.”

In addition to seeking a jury trial, damages, and the recovery of Dotson’s heart, the plaintiffs are also asking the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama to issue an injunction against Commissioner Hamm and Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences Director Angelo Della Manna.

“Defendant Commissioner Hamm Defendant and ADFS Director Manna could halt or contribute to halting the constitutional violations pleaded herein. Commissioner Hamm has the authority to oversee the handling of the remains of a deceased incarcerated individual who dies in ADOC custody and return them to Plaintiffs, as well as to instruct wardens to follow the law by requiring notification to and approval by the next of kin when organs are retained after there is a death in ADOC custody,” the complaint said. “Defendant ADFS Director Manna has the authority to instruct ADFS medical examiners not to remove organs or tissues from a body undergoing an autopsy without permission from the next of kin.”

In an interview on the case, Dotson family’s attorney Lauren Faraina called it “so grotesque and disrespectful and unacceptable” to take a vital organ from someone “without the family knowing.”

In further comment to Law&Crime, Faraina said it “appears that prison leadership cannot even be trusted with handling the remains of the people who die under their watch.”

“In the midst of grieving Brandon Dotson’s untimely death, his family is having to fight to get the most basic answers about how he died, and why the Alabama Department of Corrections returned his body without his heart. At this time we do not know where his heart is. It is the state’s responsibility to keep those who are in its prisons safe from harm,” the Dotson family lawyer said. “The ADOC failed to do that for Brandon, as they have for dozens of other individuals this year.”

Faraina also confirmed to Law&Crime that Dotson was ultimately denied parole, “like 97% of the people who come up for parole in Alabama.”

“We do not know whether he was alive at the time of the hearing or whether he knew the results before he died,” she said.

Law&Crime reached out to the Alabama Department of Corrections for comment on Dotson’s death and the lawsuit.

“The ADOC does not conduct its own autopsies and we do not comment on matters pending litigation,” ADOC said in response.

Read the lawsuit here.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]