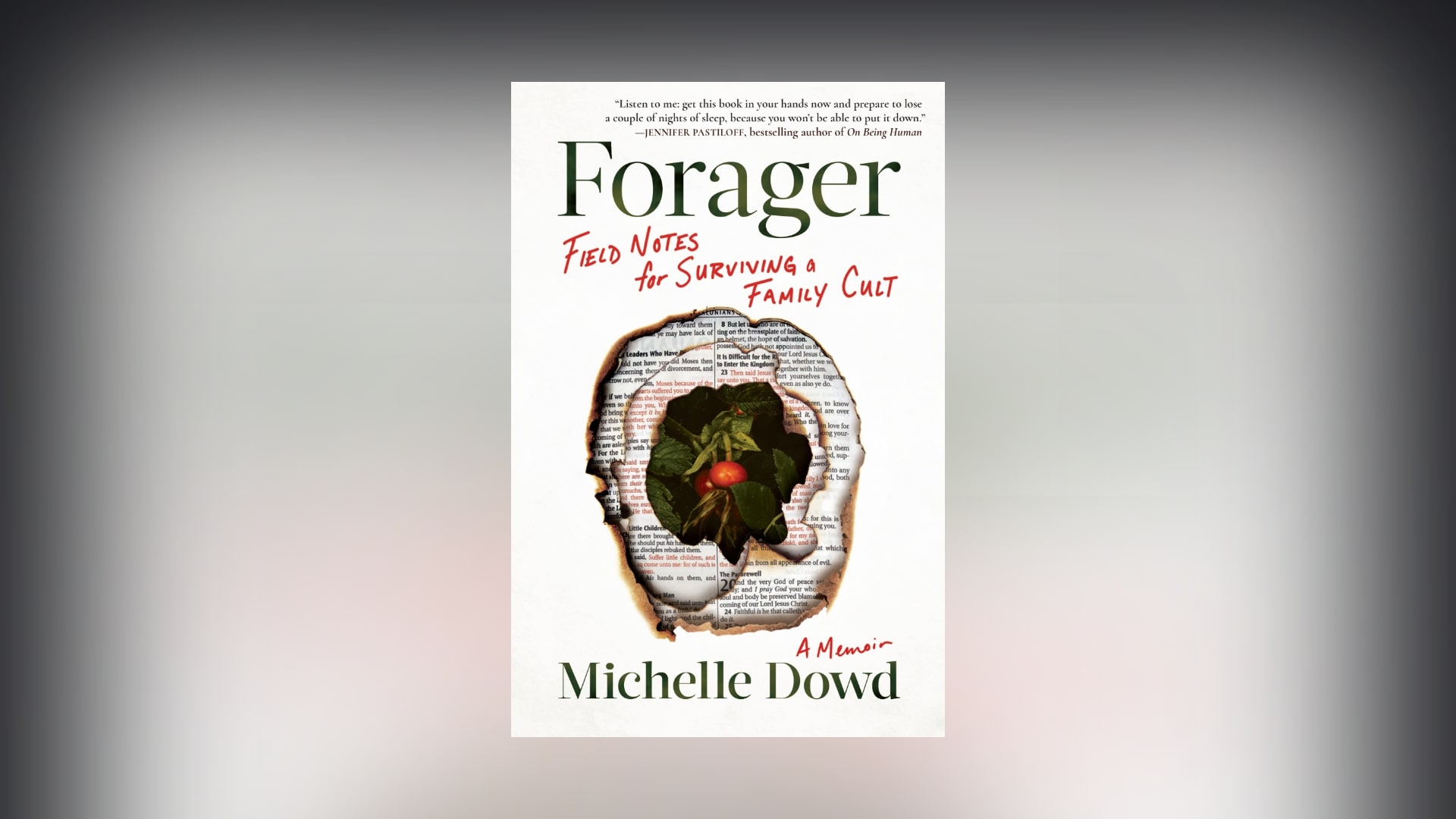

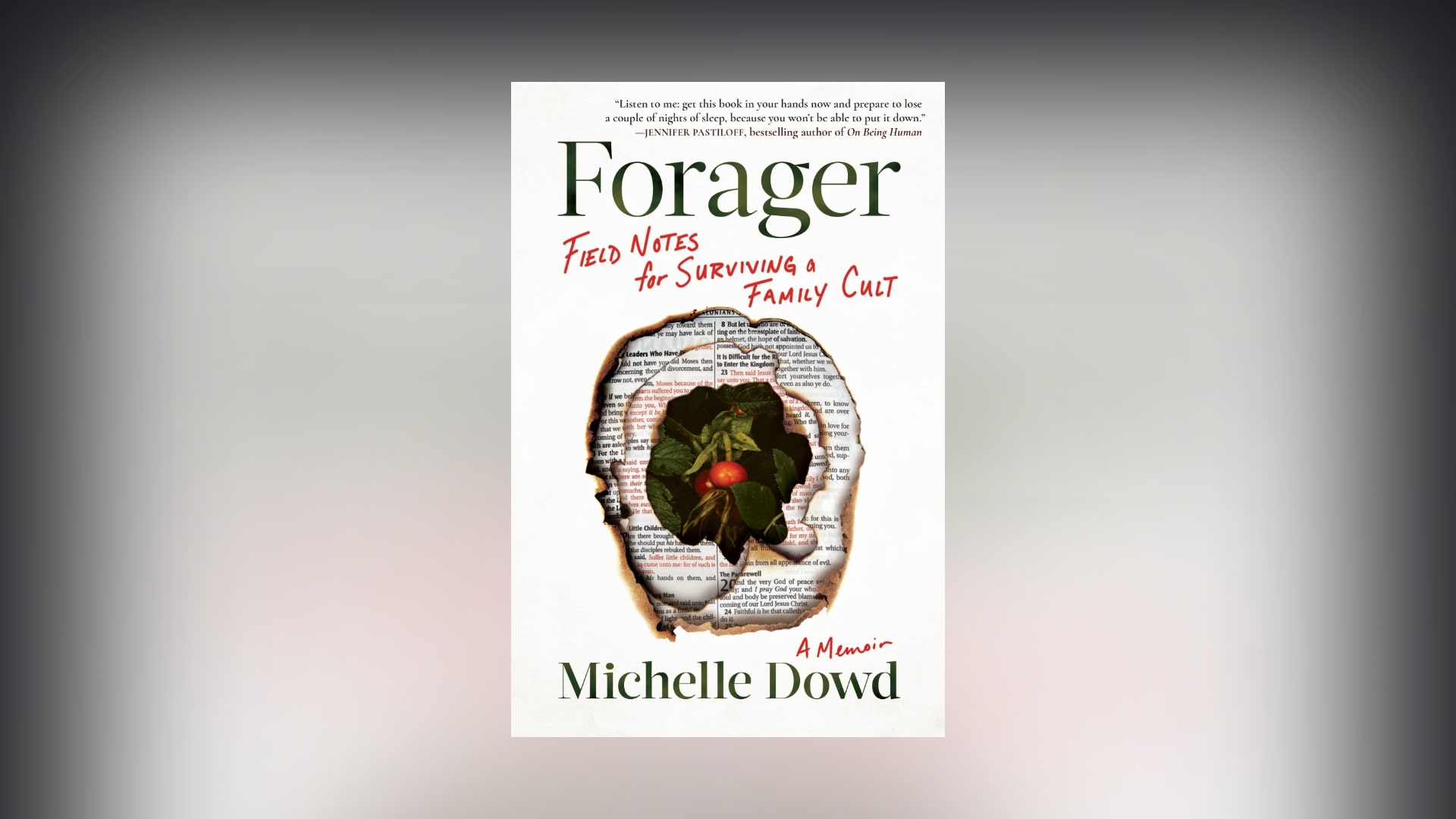

Survival, as journalist Michelle Dowd articulates in her newly released memoir Forager, can sometimes be a trickier concept to understand than it is to enact. If one is raised in the confines of a religious commune built on the twin pillars of gender-based oppression and violent abuse, such as Dowd was, is it more important to make it through the next resource-depleting drought or to hunt for a modicum of spiritual sanctuary within a restrictive community that prioritizes extreme obedience?

Much of Dowd’s childhood was spent in rough terrain with little supplies other than that which was deemed to be God-given, occupying the rural space carved out by her cult-leader grandfather where the southern California desert meets to mountains — referenced opaquely as the “Field” or the “Mountain” — between cross-country proselytizing trips with the other “followers”. At an age when one is supposed to be sheltered and protected, Dowd found herself instead teetering on the rocky edge between life and untimely death.

While her relationship with her community is meant to be understood as a largely combative one, with Dowd frequently positioned at the receiving end of punishment, the story is still tinged with the relatable heartbreak of any child scared to leave the only home they know. Bookending the memoir are descriptions of Dowd caring for her now terminally ill mother, who in many ways served as her primary abuser, in scenes that signal an aching mix of dutiful obligation and distanced forgiveness.

“But the truth is, we never know when Mother will be back. Sometimes she is gone for months at a time. We have to trust our training and believe in our own abilities. Some people think plants appear in your life at a time you most need their healing powers, and stay present for as long as you need them. I want to believe this, but Mother says that’s ridiculous. Have a plan. Survive fear. Survive with faith, because faith without work is dead.”

— Michelle Dowd, author of Forager: Field Notes for Surviving a Family Cult

Like that of a mother speaking to her child, the tone Dowd takes with her readers is one of subtle instruction. Instead of straightforward plot description or heavy-handed commentary, she opts instead to delicately intersperse her narrative with small parables and practical lessons passed down from her caretakers and other influential members of the community. Readers are not meant to interpret these instructions as benign or sentimental, however, but rather recognize them for their potential to imbue a warped sense of self-preservation and perverse response to authority. While Dowd’s mother might have survived the violent threats of her husband and other men through complicit smiling, for example, Dowd herself spends her adolescent years unlearning this response that time and time again only leads her further into danger.

Showcasing an impressive arsenal of survivalist knowledge, Dowd opens each chapter with a brief journal entry on the benefits and uses of various plants, which function metaphorically with the subject matter so as to call attention to particular moments of trauma or obstacles on her journey to escape. Dowd knows instinctively that the bark of a jeffrey pine can be extracted for food and that the yerba santa plant, when boiled down, can help ease respiratory conditions. Yet, against this framework of physical survival, she is actually reimagining what it means to survive in an emotional and psychological sense.

The need for survival also connotes the presence of danger — another principle Dowd spent much of her childhood entrenched in. What does it mean to survive, after all, if there is not a specific situation or threat to be outrun or thwarted? In the world of the Field, Dowd seems always to be dodging danger of some sort, but at times those are her moments of most fruitful foraging for self-identity.

With the keen eye of a child observing the world of the adults around her without any real agency within it, Dowd also makes a point to document the small instances of transgressions displayed by other women in the Field. Frozen chocolate chip cookies, pill bottles of Midol and contraband fashion magazines are laid out by Dowd as evidence that even those who outwardly claim to be the most devout still seek expressions of their own identities beyond the suffocation of the group’s compulsive homogeneity. Dowd is not the only Field member foraging for ways to maintain a sense of self.

Forager is a stunning memoir, which elucidates the terrifying beauty of the natural world in which Dowd is raised, set against a stark backdrop of religious extremism. Dowd probes general questions of what it means to survive, to which anyone who has experienced trauma can relate, while also excavating the specific horrors of a cult lifestyle through the lens of a child questioning her own indoctrination.

The real trick to survival, Dowd argues, is figuring out what specific aspects of yourself you want to live on. What she spends the pages of her memoir foraging for is an answer to this question.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]