Left: Judge Sarah B. Wallace presides over the final day of a hearing for a lawsuit to keep former President Donald Trump off the state ballot, Friday, Nov. 3, 2023, in Denver. (AP Photo/Jack Dempsey, Pool)/ Right: Republican presidential candidate former President Donald Trump gestures after speaking Wednesday, Oct. 11, 2023, at Palm Beach County Convention Center in West Palm Beach, Fla. A judge has rejected an attempt by Trump to dismiss a lawsuit seeking to keep him off the ballot in Colorado, ruling that his objections on free-speech grounds did not apply. The decision paved the way for a trial over whether a constitutional “insurrection” clause can bar him from running again for the White House. AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell

To convince a judge in Colorado that Donald Trump should remain on the ballot ahead of the 2024 election despite claims from a group of voters that he is disqualified under the Constitution’s insurrection clause, lawyers for the former president argued the violence of Jan. 6, 2021, wasn’t Trump’s fault but the product of “unrequited love” from extremists, much like a “stalker and their victim.”

Scott Gessler, Trump’s attorney in the case brought by six Republicans and one unaffiliated voter, made the comparison during closing arguments at the trial in the Mile High state. Conceding to 2nd Judicial District Judge Sarah Wallace that the point didn’t fare well under scrutiny during the six-day trial, he nonetheless offered it again to invoke the film “Dumb and Dumber.”

In the film, actor Jim Carey pursues a woman who has no interest in him. When he asks her, “What do you think the chances are that a girl like you will like a guy like me?” she tells him it is a one-in-a-million shot and Carey replies: “So you’re telling me, there’s a chance.”

“To say Trump had a relationship with the far right-wing extremists would be analogous to saying this character had a relationship with this woman. There was no relationship except in one person’s head,” Gessler said, before adding that a “more sinister” analogy would be the dynamic between John Hinckley and Jodie Foster.

Hinckley wanted to impress Foster by assassinating people and when legal experts testified on behalf of the voters in Colorado and argued that Trump’s commentary was intended to inflame or comfort those who would do violence in his name, Gessler pointed to Hinckley.

Trump’s relationship is defined “at best [as] unrequited love on behalf of far right-wing extremists who may like or be inspired by [him],” Gessler said. “And there’s no evidence it went the other way. To call it a relationship is like saying a stalker and their victim have a relationship. It is just wrong.”

But Sean Grimsley, an attorney representing the petitioners, argued that the public record suggests otherwise and the examples long precede even his flagrant Jan. 6 remark to rioters: “We love you.”

Left: Sean Grimsley, attorney for the petitioners, delivers closing arguments during a hearing for a lawsuit to keep former President Donald Trump off the state ballot in court, Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2023, in Denver. (AP Photo/Jack Dempsey, Pool). Right: Scott Gessler, attorney for former President Donald Trump, delivers closing arguments in a hearing for a lawsuit to keep Trump off the state ballot, Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2023, in Denver. (AP Photo/Jack Dempsey, Pool)

Trump failed to disavow the Proud Boys when asked, telling them “stand back and stand by,” he said.

Expert Peter Simi, a Chapman University sociologist who has studied far-right extremism for more than 20 years, testified that Trump’s language at the Ellipse was a “call to violence.” He noted Trump’s use of the word “fight” over 20 times.

While Trump may have said “peaceful” once, Simi said the former president does not “conjure rhetoric from thin air” nor does he “just so happen to choose language that would resonate with his far-right extremist supporters.”

“He knew precisely what he was saying based on a five-year history of call and response where he would either call for violence and then not condemn it or there would be violence and he would praise it,” Grimsley said.

When Oath Keepers and Proud Boys were on trial for seditious conspiracy this year and last, evidence emerged repeatedly that members were buoyed by Trump’s rhetoric on Jan. 6 and prior to it. His “stand back and stand by” comment exploded membership for the Proud Boys, seditious conspirators like Proud Boy Jeremy Bertino and others told a federal jury. When Trump-appointed U.S. District Judge Tim Kelly sentenced Proud Boys and former InfoWars contributor Joe Biggs for his role in the seditious plot to forcibly stop the transfer of power, Kelly specifically highlighted how Biggs was inspired by Trump’s words to physically fight their perceived enemies like antifa.

Grimsley noted too: Trump has suggested that a Black protester should be “roughed up.” He said there were good people on both sides at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017 following the murder of Heather Heyer. Trump praised a lawmaker who body-slammed a reporter. He said “I love Texas” after a bus of supporters for Joe Biden was almost run off the road by Trump supporters.

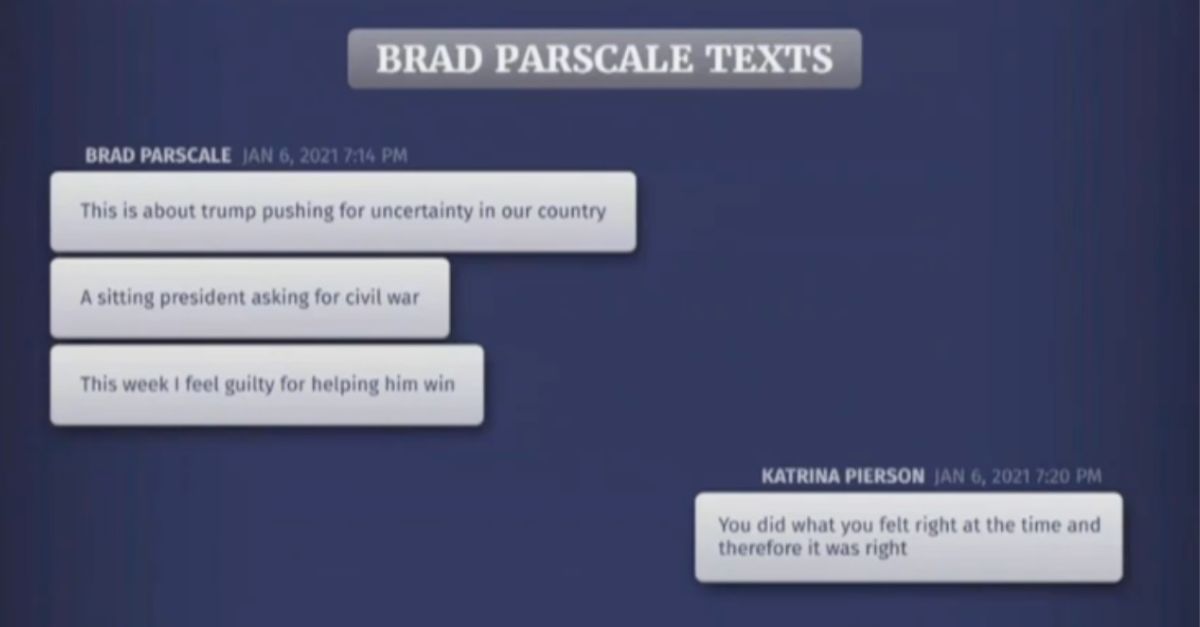

If there were questions over Trump’s intent, Grimsley asked Wallace to consider the words of onetime campaign manager Brad Parscale. In a message to then-campaign adviser Katrina Pierson on the night of Jan. 6, Parscale called Trump “a sitting president asking for a civil war.”

“That’s how people who knew Trump took what he said that day,” Grimsley said.

Jan. 6 committee presentation exhibit of Brad Parscale text

There was “no innocent explanation” for Trump’s 2:24 p.m. tweet attacking Mike Pence as the riot was in full swing and his request to “stay peaceful” and “support law enforcement” on social media had no practical effect, Grimsley argued.

“He didn’t condemn them. And it wasn’t until it was obvious that the riot would fail that he told people to go home,” Grimsley said.

Alternatively, Trump’s lawyers told Judge Wallace there was “no evidence Trump knew [rioters] were armed” and Gessler excoriated findings of the House Select Committee to Investigate the Jan. 6 Attack on the U.S. Capitol as “grandstanding,” partisan and unworthy of the court.

But Wallace agreed to admit the report on a conditional basis at the start of the trial and that report contains evidence like former White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson’s sworn testimony that Trump wanted a large crowd at his speech and called for guests to be rushed through magnetometers despite explicit warnings from the Secret Service that weapons were in the mix.

“They are not going to hurt me,” Hutchinson recalled Trump saying that morning.

In Colorado, witnesses for Trump like Amy Kremer, chair of Women for America First, called Trump’s supporters on Jan. 6 “happy warriors.”

Grimsley countered Wednesday that many of those same people brought guns, knives, Tasers, sharpened flagpoles, scissors, hockey sticks, pitchforks, bear and pepper spray. They used items stolen from the Capitol as weapons to halt proceedings like police barricades, broken scaffolding, construction equipment, trash cans and more. They also took batons and riot shields from officers.

Pierson may have seen people “happily milling about” at the speech at the Ellipse, but she wasn’t at the Capitol, Grimsley said.

Under Section III of the Fourteenth Amendment, those who swear to uphold the Constitution are barred from serving in office if they engage in an insurrection. Nowhere in the Constitution does it define the use of weaponry or coordinated organization as an insurrection requirement.

The events of Jan. 6 had both, Grimsley said, noting the presence of Oath Keepers and Proud Boys who attacked in groups on all sides of the building while using tactical gear and communications to aid them.

Debates over the bloodshed of Jan. 6 or the mere definition of the word “insurrection” were not the only points raised. There was ample argument over whether Trump is an “officer” of the United States statutorily speaking. Trump’s lawyers say he is not, but Grimsley noted in other lawsuits brought by Trump, he has called himself such, like in his civil fraud case in New York, for example. He has argued the president is an officer of the United States in a bid to remand that case.

Supporters of Donald Trump at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana

Trump witness and scholar Robert Delahunty — who conceded in court that he was not an expert in Section III before testifying on it — ignored the historic use of the term in congressional debates or proclamations or historic definitions, the petitioners argued.

The parties asked the judge to consider what words like “support” and “defend” mean in the context of the constitutional oath. The same goes for the word “engage” in “engaging in an insurrection” under Section III.

Trump’s experts interpreted it to mean taking up arms; the voters say incitement through speech is enough and pre-Civil War cases didn’t rely on violence or arms. The House has refused to seat members for far less: One lawmaker gave his son $100 when he went to join the Confederate Army. Another was removed for writing a Rebel-sympathetic op-ed.

A lawyer for the Colorado GOP, which filed as an intervenor in the case, argued none of this matters since Griswold’s role is entirely ministerial and nominee qualifications are still based on what the party determines.

But the voters say “it makes no sense” to force them and millions of others to waste their vote or time on “an unqualified candidate only to say ‘oops,”” Grimsley said.

Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch found in Hassan v. Colorado that states also have a legal interest in protecting the integrity of elections by excluding candidates who are prohibited from assuming office.

Section III requires a supermajority to remove someone, he added.

“How could it be that Congress, by simple majority, decides whether qualification exists in first place but has to vote by supermajority to remove it?” he asked the court.

Trump’s lawyers spent weeks trying and failing to get the case thrown out altogether, mostly arguing the lawsuit violated Trump’s First Amendment rights and the rights of voters who want to vote for him. But in closing arguments, they stuck closely to the recent decisions in Michigan and Minnesota where courts have rejected attempts to strike Trump from the primary ballot.

Those rulings alone should guide Wallace, Gessler urged.

On rebuttal, the voters’ attorney underlined “Trump’s disdain for the Constitution” and asked the judge not to forget a December 2022 post from the former president on Truth Social where he continued to decry the “stolen” election and wrote, “Massive fraud of this type and magnitude allows for the termination of all rules, regulations and articles, even those found in the constitution.”

“This is exactly why we have Section III. People who have violated their oath have shown themselves to be untrustworthy and unworthy of taking the oath again. this right here, is what four more years of Trump could look like,” Grimsley said.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]