Richard Nixon speaks during White House news briefing in Washington. (AP Photo/Henry Burroughs.), Special counsel Jack Smith (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File), Donald Trump (AP Photo/David Yeazell)

The special counsel on Monday urged the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court not to create a world where presidents can get away with anything, even murder, just by asserting absolute immunity from prosecution for official acts.

Jack Smith repeatedly emphasized at length that while the federal Jan. 6 charges former President Donald Trump faces do stem from his time in office, the alleged conspiracy to defraud the United States, conspiracy to obstruct, and conspiracy against rights amounted to “substantial private conduct in service of petitioner’s private aim” — aided by “several private individuals” (including attorneys) and through “private means.”

Here are some of the top takeaways from the long-anticipated brief on the question: “Whether and if so to what extent does a former President enjoy presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for conduct alleged to involve official acts during his tenure in office.”

The Founding Fathers “never endorsed criminal immunity for a former President,” and Richard Nixon’s acceptance of a Watergate pardon after resigning is a strong indication that Nixon knew there was no such immunity

Here, Smith appealed to history to rebut Trump’s argument that the Framers envisioned an America where the president is unaccountable under the law once out of office, pointing to President Richard Nixon’s resignation and subsequent pardon as proof that both Nixon and President Gerald Ford understood there was criminal liability for Watergate.

“The Framers never endorsed criminal immunity for a former President, and all Presidents from the Founding to the modern era have known that after leaving office they faced potential criminal liability for official acts. The closest historical analogue is President Nixon’s official conduct in Watergate, and his acceptance of a pardon implied his and President Ford’s recognition that a former President was subject to prosecution,” Smith wrote. “Since Watergate, the Department of Justice has held the view that a former President may face criminal prosecution, and Independent and Special Counsels have operated from that same understanding. Until petitioner’s arguments in this case, so had former Presidents.”

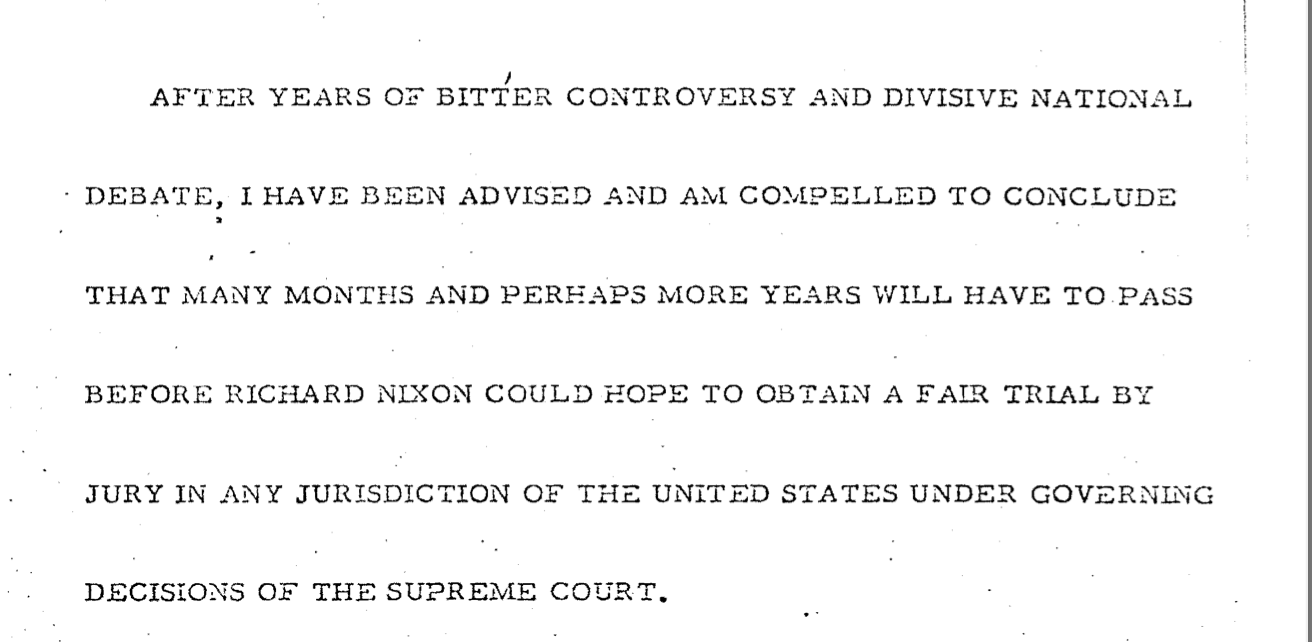

Smith added in a link to Ford’s statement on pardoning Nixon, in which the then president expressed that he did not think Nixon could get a fair criminal trial.

“After years of bitter controversy and divisive national debate, I have been advised and am compelled to conclude that many months and perhaps more years will have to pass before Richard Nixon could hope to obtain a fair trial by jury in any jurisdiction of the United States under governing decision of the Supreme Court,” Ford said.

Prosecuting Trump will not have a chilling effect on future presidents

The special counsel, arguing that presidential immunity from “private civil damages actions does not extend to federal criminal prosecutions,” said that “layered safeguards” exist to prevent the kind of politically motivated and weaponized prosecutions that Trump has complained of.

“A criminal prosecution must be brought by the Executive, with strong institutional checks to ensure evenhanded and impartial enforcement of the law; a grand jury must find that an indictment is justified; the government must make its case and meet its burden of proof in a public trial; and the courts enforce due process protections to guard against politically motivated prosecutions,” Smith said. “Collectively, these layered safeguards provide assurance that prosecutions will be screened under rigorous standards and that no President need be chilled in fulfilling his responsibilities by the understanding that he is subject to prosecution if he commits federal crimes.”

Trump’s “radical suggestion” would “free the President from virtually all criminal law,” even murder charges

Federal criminal law applies to the President. Petitioner suggests that unless a criminal statute expressly names the President, the statute does not apply. That radical suggestion, which would free the President from virtually all criminal law—even crimes such as bribery, murder, treason, and sedition—is unfounded. That rule finds no support in this Court’s decisions. Nor is it supported by opinions of the Department of Justice, which have instead construed statutes to apply to the President unless doing so creates a serious risk of infringing the President’s constitutional powers. That more modest interpretive principle has no application to the crimes charged here, which pose no risk of unconstitutionally regulating the President’s conduct.

Avoiding an impeachment conviction in the political world, as happened twice in Trump’s presidency, is not a get out of jail free card in the real world

The Impeachment Judgment Clause, U.S. Const. Art. I, § 3, Cl. 7, does not establish a rule requiring a President’s impeachment and conviction before a former President may be prosecuted. The text of the clause clarifies that an impeached and convicted President may nevertheless be prosecuted and thus expressly recognizes that former Presidents are subject to federal criminal prosecution. Petitioner acknowledges that prosecution is permitted after impeachment and conviction, which refutes many of the other arguments in his brief. And text, structure, and history contradict petitioner’s assertion that the Impeachment Judgment Clause implicitly makes Senate conviction a condition precedent to prosecution. Impeachment is an inherently political process, not intended to provide accountability under the ordinary course of the law. Criminal prosecution, in contrast, is based on facts and law, and is rigorously adjudicated in court. Adopting petitioner’s position would thwart the ordinary application of criminal law simply because Congress, in administering the political process of impeachment, did not see fit to impeach or convict.

That there have not been other prosecutions of former presidents is not a sign that it can’t be done, just that Trump’s alleged conduct is that “unprecedented”

“The absence of any prosecutions of former Presidents until this case does not reflect the understanding that Presidents are immune from criminal liability; it instead underscores the unprecedented nature of petitioner’s alleged conduct. And none of the dissimilar historical examples on which petitioner relies suggests otherwise,” Smith said.

Anticipating that the justices might find a former president has “some immunity” from being prosecuted for official acts, the special counsel argued that even if that is so the case can still proceed

Next, the special counsel asserted that the “private conduct” alleged in the indictment is enough to go to trial.

“First, a President’s alleged criminal scheme to overturn an election and thwart the peaceful transfer of power to his lawfully elected successor is the paradigmatic example of conduct that should not be immunized, even if other conduct should be,” the special counsel said. “Second, at the core of the charged conspiracies is a private scheme with private actors to achieve a private end: petitioner’s effort to remain in power by fraud. Those allegations of private misconduct are more than sufficient to support the indictment.”

Smith then dove back into history for Founding-era authorities to draw a distinction between impeachment and criminal prosecution — with a reference to Justice Clarence Thomas’ dissent in Trump v. Vance on the subject of absolute immunity:

The Framers’ most relevant writings provide no support for immunity of the type that petitioner claims. “James Wilson, a signer of the Constitution and future Justice of this Court, explained to his fellow Pennsylvanians that ‘far from being above the laws, [the President] is amenable to them in his private character as a citizen, and in his public character by impeachment.”” Vance, 591 U.S. at 816-817 (Thomas, J., dissenting) (quoting 2 The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution 480 (J. Elliot ed. 1891) (Debates on the Constitution)). Wilson therefore recognized that prosecution was the means of holding a President accountable in his “private character” for criminal acts, while impeachment was the means of addressing his “public character” as office holder. “James Iredell, another future Justice, observed in the North Carolina ratifying convention that ‘[i]f [the President] commits any crime, he is punishable by the laws of his country.’” Id. at 817 (Thomas, J., dissenting) (quoting 4 Debates on the Constitution 109). Alexander Hamilton likewise confirmed that a President, unlike a King, would be “liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.”

A shout-out to Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s 1998 Georgetown Law Journal article, “The President and the Independent Counsel,” to counter the argument that former presidents can never be prosecuted

Those historical sources and the DOJ materials that petitioner cites reflect the longstanding Department position that although a sitting President enjoys temporary immunity from criminal prosecution— for all conduct, public and private—he may be prosecuted after leaving office. Amenability to Indictment, 24 Op. O.L.C. at 255; see also Brett M. Kavanaugh, The President and the Independent Counsel, 86 Geo. L.J. 2133, 2161 (1998) (noting that if Congress declines to “impeach and remove” a sitting President, he cannot face criminal prosecution “until his term in office expires”).

What about President Barack Obama’s drone strikes, Teddy Roosevelt, and John Quincy Adams?

In Trump’s brief, he argued that U.S. “political history” counseled against formally charging a president even as people broadly accused those presidents of engaging in “criminal” behavior. Trump pointed to the “corrupt bargain” between John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson and the “Trail of Tears,” Teddy Roosevelt and Japanese American internment camps during World War II, Bill Clinton “repeatedly launch[ing] military strikes in the Middle East on the eve of critical developments in the Monica Lewinsky scandal,” George W. Bush and WMDs, and Obama ordering a drone strike that “killed U.S. citizens abroad by drone strike without due process.”

Smith responded that each of these examples “failed to prove” Trump’s point, most of them for raising the “sort of serious separation-of-powers concerns that are absent” in Trump’s case:

Even if it is true that John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay agreed to exchange political support for an appointment following the election of 1824, see Rami Fakhouri, The Most Dangerous Blot in Our Constitution: Retiring the Flawed Electoral College ‘Contingent Procedure,’ 104 Nw. U. L. Rev. 705, 719-720 (2010), Adams was a presidential candidate, not the President, and petitioner fails to explain how the asserted political deal constituted a crime. See United States v. Blagojevich, 794 F.3d 729, 734 (7th Cir. 2015) (“[A] proposal to trade one public act for another, a form of logrolling, is fundamentally unlike the swap of an official act for a private payment.”), cert. denied, 577 U.S. 1234 (2016). Petitioner likewise identifies no court order or criminal statute that would have applied to President Jackson’s decision not to send federal forces to prevent Georgia officials from interfering with the Cherokee following this Court’s decision in Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832). See generally Joseph C. Burke, The Cherokee Cases: A Study in Law, Politics, and Morality, 21 Stan. L. Rev. 500 (1969).

Petitioner’s 20th and 21st century examples are similarly flawed. He identifies no criminal statutes that could have validly applied to President Roosevelt’s decision to intern Japanese Americans during World War II, President Clinton’s decision to launch military strikes in the Middle East, or President Obama’s decision to launch a drone strike abroad. Those examples involved quintessential exercises of the President’s Commander-in-Chief power during war or to protect the Nation from foreign threats, see U.S. Const. Art. II, § 2, Cl. 1. Attempts by Congress to regulate the President’s exercise of those authorities through the criminal laws would raise the sort of serious separation-of-powers concerns that are absent here. And petitioner’s assertion that President Clinton engaged in an “illegal quid pro quo”—granting a pardon in exchange for a thing of value—rests on speculation. Finally, petitioner makes no effort to support his contentions that President George W. Bush made knowingly false statements about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq or that any of the conduct he ascribes to President Biden would violate a criminal law.

Conclusion

The special counsel maintained that “history weighs heavily against” Trump’s absolute immunity claims and that there is a “compelling public interest in enforcing the criminal law.”

“Petitioner’s use of official power was merely an additional means of achieving a private aim—to perpetuate his term in office—that is prosecutable based on private conduct. The conspiracy centrally embraced private actors agreeing with petitioner to achieve his private end through private means,” the brief said. “In particular, petitioner is alleged to have conspired with four private attorneys and a private political consultant in his effort, as a candidate, to subvert the election results.”

Colin Kalmbacher contributed to this report.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]