An incarcerated quadruple murderer cannot sue his psychiatrist and pursue damages for alleged medical malpractice by “grossly negligent treatment” because that would allow him to profit off of his crimes, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has ruled.

In a little noticed Nov. 22 opinion, the Keystone State’s high court decided that Cosmo DiNardo, now 26, was barred by the “no felony conviction recovery” rule from “benefitting or profiting, via the civil laws, from his own criminal conduct.”

DiNardo’s July 2017 crimes horrified Bucks County and devastated the families of Jimi Patrick, 19, Dean Finocchiaro, 19, Thomas Meo, 21, Mark Sturgis, 22.

The victims disappeared over a period of days, starting with the murder of Jimi Patrick on July 5, 2017. Two days later, DiNardo and his cousin Sean Michael Kratz, now 26, murdered Dean Finocchiaro. An hour later, Mark Sturgis and Thomas Meo were murdered. Both young men were shot, but when DiNardo ran out of bullets, he drove a backhoe over Meo’s body.

Cosmo DiNardo (left) in a 2022 Pennsylvania Department of Corrections mug shot; Jimi Patrick (top left), Mark Sturgis (top right), Thomas Meo (bottom left), Dean Finocchiaro (bottom right) in Bucks County Sheriff’s Office missing person photos.

Each of the murders took place on a farm owned by the DiNardo family in Solebury, where Cosmo DiNardo lured the victims under the guise of selling them marijuana. The criminal complaint detailed that DiNardo shot Patrick with a rifle in a remote area of the property after handing the victim a shotgun that the killer claimed he was interested in selling for $800. DiNardo separately claimed he had intended to rob Finocchiaro, Meo, and Sturgis with the help of Kratz.

Instead, he murdered them all.

DiNardo used a backhoe to dig a “deep grave” where he buried the bodies of Meo, Sturgis, and Finocchiaro in a metal tank that the admitted quadruple murderer referred to as a “pig roaster.” DiNardo poured gasoline on the victims’ bodies and set them on fire. Jimi Patrick was buried in a separate grave site, one that was also dug with the backhoe.

DiNardo went on to plead guilty to the murders in 2018; Kratz was convicted of murdering Finocchiaro and convicted of voluntary manslaughter in the deaths of Sturgis and Meo. Both killers were sentenced to life in prison without parole.

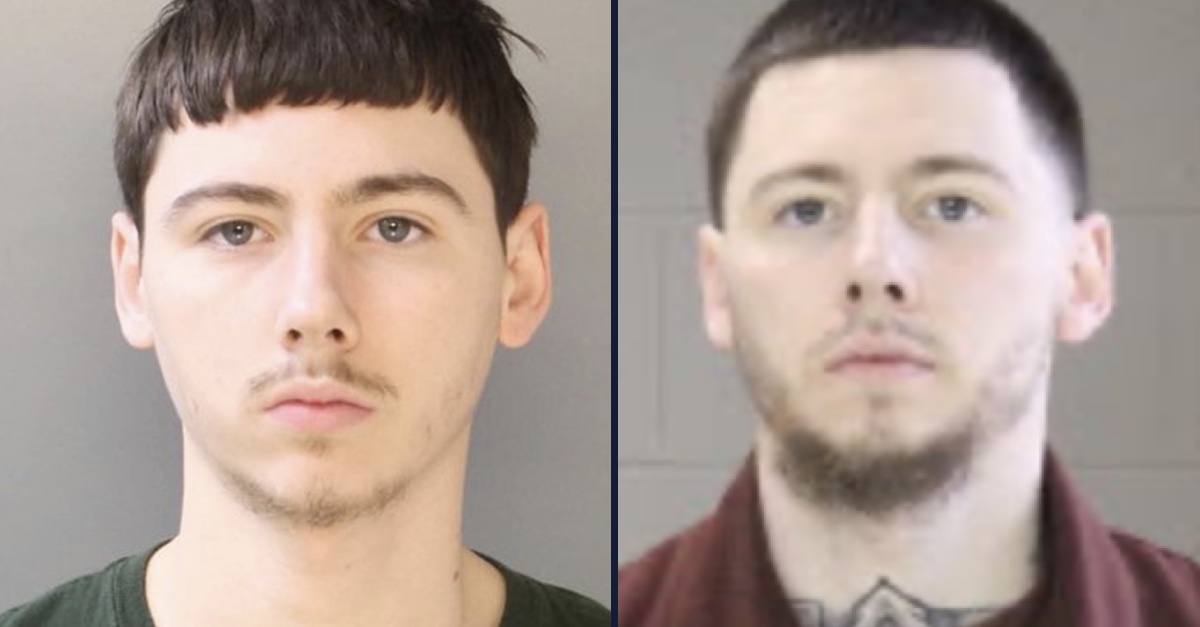

Sean Michael Kratz (left) in a 2017 mug shot, (right) in a 2022 Pennsylvania Department of Corrections mug shot.

The case established that prior to the murders Cosmo DiNardo had being seeing a psychiatrist, Dr. Christian Kohler, to be treated for bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder — treatment that involved taking antipsychotic medications. Kohler’s care of DiNardo prior to the murders was the focus of DiNardo’s failed lawsuit, which was filed by his mother Sandra DiNardo on his behalf.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court documented that DiNardo attacked his father with a brick in December 2016, “chased him with a pellet gun,” and threatened to break into his aunt’s home to “kill his aunt’s parents and young children in an attempt to obtain firearms that he believed she possessed.”

That incident made DiNardo a patient of Kohler’s, and the psychiatrist issued a recommendation for involuntary commitment in a mental health facility, the opinion noted.

While at Brooke Glen Behavior Hospital, DiNardo threatened staff and expressed a desire to kill his family members. There, he was “deemed to be suicidal and homicidal, and to pose a risk to those around him.” But when DiNardo was released one week later, the high court opinion continued, Dr. Kohler “examined him and concluded, despite his homicidal conduct at Brooke Glen, that DiNardo was not a risk to himself or others.”

In February 2017, there was another incident at Temple University, where DiNardo was in a fight.

“Despite having knowledge of this incident,” the opinion said, Dr. Kohler “found that DiNardo was in ‘remission,”” and the psychiatrist “reduced the dosage of DiNardo’s antipsychotic medication and lithium.”

Just five months later, DiNardo committed the murders.

In the Pennsylvania Supreme Court case, DiNardo asked the justices, through his mother, to find that Kohler’s “grossly negligent psychiatric care from December 2016 onward” and failure “to adequately assess [DiNardo’s] risk for violence” entitled DiNardo to compensatory damages.

DiNardo attempted to draw a distinction between being compensated for alleged medical practice and profiting off of his crimes.

“According to Appellant, the compensatory damages that DiNardo seeks are not the result of his criminal convictions, but, rather, are due to ‘the violent psychosis brought on by Dr. Kohler’s gross negligence,’” the opinion noted.

DiNardo asserted that, as a matter of public policy, psychiatrists like Kohler should not get a “free pass” to, for example, take “DiNardo off all of his psychotropic medications despite having specific knowledge that DiNardo was highly dangerous to himself and others when his medications were reduced[.]”

The high court, however, indicated this case wasn’t a particularly close call, especially since DiNardo himself admitted to four intentional, willful murders.

“In short, our case law, while somewhat limited, firmly establishes that, under both the no felony conviction recovery rule and the in pari delicto [Latin for ‘in equal fault’] doctrine, persons convicted of serious crimes must bear the losses stemming from their criminal acts, and, as a matter of public policy, will not be permitted to shift responsibility for these losses to others,” the Pennsylvania Supreme Court said. “Stated another way, injuries that flow from volitional criminal conduct cannot provide a basis for a recovery in tort.”

Beyond that, the opinion warned, to accept DiNardo’s theories could have a chilling effect on the “practice of psychiatric medicine” more broadly:

Not only would the judiciary and the criminal justice system be negatively impacted by allowing one to recover civil damages for injuries arising from serious criminal conduct, but, in the context of this case, there could be detrimental effects on the practice of psychiatric medicine. Allowing the recovery of damages from a mental healthcare provider for a patient’s criminal conduct could undermine trust between the patient and psychiatrist; encourage psychiatrists to refuse to treat, or avoid treating, certain patients; spur institutionalization and excessive medication out of concern for financial liability should patients be released from care and commit crimes; and would not respect the difficulty mental healthcare professionals face in predicting whether an individual poses a risk of violence.

Even when viewing the DiNardo case “in the light most favorable” to him, the justices determined, it was clear that his pursuit of compensatory damages was “not sustainable,” as it ran counter to the “no felony conviction recovery” rule.

“[T]he theories of liability, causes of action, and damages alleged all flow from DiNardo’s own volitional homicidal conduct, to which he pleaded guilty. This being the case, under the no felony conviction recovery rule, the causes of action asserted and claims for damages are not sustainable,” the opinion concluded. “Thus, Appellant’s complaint fails as a matter of law.”

A brief concurrence penned by Justice Kevin M. Dougherty observed that DiNardo’s first-degree murder guilty pleas made this case clearer than other cases might be when analyzing the “no felony conviction recovery” rule.

“[B]ecause the case before us concerns a guilty plea to first-degree murder, the majority appropriately declines to ‘address the applicability of the rule where an individual’s actions are deemed to be less than intentional, such as in the context of a judicial finding of insanity or a verdict of guilty but mentally ill, where the calculus regarding the rule’s application may differ,’” Dougherty wrote.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]