Mariana Rocha and her son Jackson Laparl, 6, visit a portrait of Rocha’s cousin Joaquin Oliver, right, part of a display of portraits of the 17 students and staff of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School who were killed, during a community commemoration on the five-year anniversary of the shooting, Tuesday, Feb. 14, 2023. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

A federal appeals court smacked down the National Rifle Association’s (NRA) challenge to a Florida law banning young people under the age of 21 from purchasing or owning firearms, in an opinion that turned the Supreme Court’s new Second Amendment analysis on its head.

Last June, Justice Clarence Thomas led the Supreme Court’s six-member majority to gut New York State’s handgun law in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen. In Thomas’s opinion, the conservative court leaned hard on the need for current gun laws to be supported by “this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” In the wake of the Bruen decision, multiple federal courts have struck down gun-control laws —including one circuit court that ruled to allow known domestic abusers to possess guns —on the basis that they had no sufficient historical counterpart.

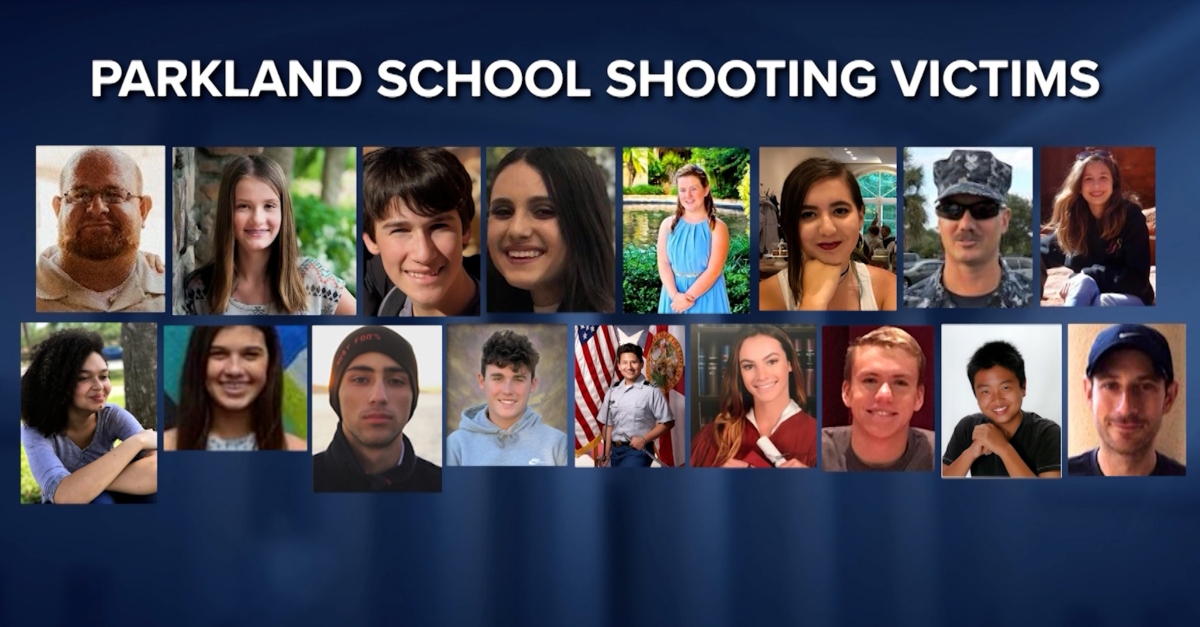

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit, however, had a very different take on history in its ruling Thursday to uphold Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act. The act was passed by the Sunshine State’s legislature in response to the 2018 mass shooting in Parkland, Florida, that left 17 dead and 17 injured.

U.S. Circuit Judge Robin Rosenbaum, a Barack Obama appointee on the 11th Circuit, wrote the opinion for the three-judge panel, which included U.S. District Judge Anne C. Conway (a George H.W. Bush appointee (sitting by designation in the case) and U.S. Circuit Judge Charles Wilson, a Bill Clinton appointee. Wilson penned a six-line concurrence to say that he concurs with the court’s ruling and reasoning, but that he would have pushed the case off until after the next Florida legislative session, which might render the case moot.

Rosenbaum began her opinion, as if speaking directly to Justice Thomas, addressing “historical tradition” head on and offering a litany of grisly 19th century headlines about gun violence committed by individuals under the age of 21:

In Ohio, a 19-year-old son shoots and kills his father to “aveng[e] the wrongs of [his] mother.” In Philadelphia, an 18-year-old “youth” shoots a 14-year-old girl before turning the gun on himself “because she would not love him.” In New York, a 20- year-old shoots and kills his “lover” out of jealousy. In Washington, D.C., a 19-year-old shoots and kills his mother, marking another death due to “the careless use of firearms.” In Texas, a 19-year-old shoots a police officer because of an “[o]ld [f]eud” between the police officer and the 19-year-old’s father. These stories are ripped from the headlines—the Reconstruction Era headlines, that is.

Rosenbaum next noted that “in the 150 years since Reconstruction began, guns have gotten only deadlier.” Rosenbaum wrote that even as far back as the 1800s, “State governments have never been required to stand idly by and watch the carnage rage” — and that when Florida passed the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act, it did so as part of a long-standing historical tradition.

Rosenbaum pointed out that if we are talking about the “history and tradition” of our nation’s gun laws, the place to look is not the Founding Era, but rather, Reconstruction. That is so, the judge explained, “because the Fourteenth Amendment is what caused the Second Amendment to apply to the States.” Rosenbaum wrote that given the Fourteenth Amendment’s timing, any context for interpreting the right to bear arms should be taken from the same period.

Rosenbaum also took aim at the applicability of the Bruen decision in any potential future appeal of the case at hand. She wrote that Bruen dealt only with the right to publicly carry firearms — and that the Supreme Court found that the historical rules for open carry were essentially the same in 1791 and 1868. Rosenbaum. however, called the interpretation of the more general right to keep and bear arms “very different” during the two eras. Moreover, Florida’s restriction on young adults precludes those under 21 only from buying firearms while still leaving that age group free to possess and use firearms of any legal type.

Rosenbaum also engaged in an application of Bruen’s framework and concluded that “it’s not clear whether 18-to-20-year-olds ‘are part of ‘the people’ whom the Second Amendment protects.”” Even historically, people within that age range have not enjoyed the full range of civil rights that adults did, the judge reasoned. The appellate judge supported this contention with statutes written at the time (an entire appendix of which are attached to the court’s decision), but also with newspapers that represented general public discourse about the Second Amendment.

But because Florida did not argue that 18-to-20-year-olds are entitled to lesser Second Amendment rights, the circuit court engaged in a Bruen-inspired search for a “historical analogue” to support Florida’s ban — and found it. Rosenbaum cited an 1855 Alabama prohibition on minors selling, giving, or lending knives, air guns, or pistols, along with similar statutes passed at the time by Tennessee, Arkansas, and Kentucky.

Rosenbaum also noted that the weapons laws coincided with passage of statutes restricting alcohol to minors on the basis that “both represented dangers to minors’ safety.” That is what Florida was trying to do when passing a law to “enhance public safety” by limiting school gun violence, the judge reasoned.

During the case, the NRA advanced its own historical argument: that a historical requirement that young people join the militia (in which those individuals would presumably use firearms), supports the same individuals’ right to purchase firearms. Rosenbaum unceremoniously dispensed with that argument: “the NRA mistakes a legal obligation for a right.”

You can read the full ruling here.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]